Smalto the man.

The Tokyo Olympics have been postponed a year and Major League Baseball may not begin its season till July. But if you know where to look – or depending on your perspective, where not to – you can find manifold action in sporting summers already past.

But I’m warning you now, despite my best intentions and those of several actors in this true story, it remains, in parts, not suitable for screen-viewing near coworkers and children (who occupy one category anyway, in this time of mandatory home shelter and remote learning).

In the summer of 2018, France beat Croatia for its second-ever World Cup – which entitled them to a visit to the Elysée Palace to receive the Legion of Honor – a ceremony not held till last summer, June of 2019.

The proud, dashing French side, known as Les Bleus the world over, naturally had to wear that shade for the occasion. But what you might not know is how exactly it was provided and by whom – and in that lies a sporting story yet untold, perhaps no replacement for a full Olympiad but a tale that nevertheless includes one of the greatest perfumers of all time, a deceased Italian tailor, a Mumbai expat in a counterfeit market in China, and a manufacturing complex in Watford, England (a 104,000-person county 15 miles northwest of London whose football club wears a stag on its shield despite being called the Hornets).

Oh, and Jennifer Lopez, Ariana Grande, Formula 1 racing and Nicki Minaj. And Gay Talese, new journalist, sharp dresser.

Bang bang (bang bang).

The Italian tailor hailed from Reggio di Calabria, in the south of Italy, but had international ambition. Born in 1927, he created his first outfit at the age of 14, for a friend, and by 1962 had already apprenticed himself to Sam Harris, maker of Jack Kennedy’s suits, and Parisian tailor Antonio Cristiani, a cousin of journalist Gay Talese’s father.

And so it was that in 1962, Francesco Smalto, his name hitherto unknown but his ability to drape and cut fabric highly refined, opened his own men’s shop in Paris. His style was Italian in its lack of boxy, severe Savile Row structure, in its obeisance to the body’s natural lines, yet apparently no less comfy for being so. His was a rakishness that managed to provide wiggle room. His work on a suit involved 33 steps.

The French press labeled him “the man who dresses men” – which seems a bizarre sobriquet, as if the ‘60s had been a time of reverse-Handmaid’s Tale gender inequality in Paris. But it was more likely used to emphasize the prominence of Smalto’s clientele, among them actors Jean-Paul Belmondo and Roger Moore and statesmen such as King Hassan II of Morocco and France’s own eventual leader, Francois Mitterand.

In 1983, The New York Times elevated the former pupil to the level of his teacher: “Cifonelli, Cristiani, and Smalto are among the best custom tailors in Paris.”

You also know you’ve made it when you’re procuring prostitutes for Omar Bongo – the long-time dictator of Gabon, which was the only former African colony of France to vote against independence (de Gaulle granted it anyway).

In a trial 12 years after the Times pronounced him tops, in 1995, Smalto told a court that he and two others brought call girls to Bongo when they visited him in return for $600,000 per year in tailoring business.

In today’s world, international sex trafficking of that sort would arouse calls for the person’s blacklisting from every corner of the fashion world – his cancelling, in current parlance – not to mention a severe criminal punishment that would render the shunning practically unnecessary.

But in the France of that era, Smalto was given a 15-month suspended prison sentence and a 600,000-franc fine for the crime of “aggravated pimping.” He didn’t sell the business for another six years.

Francesco Smalto, who passed in 2015, at 87.

Things are gonna get stranger from here – but none of that is to diminish the heinousness of international prostitution. As is everywhere apparent globally now, life can be a surreal mixture of humor and horror.

After Smalto’s departure, a whole series of leaders came and went rapidly, including Smalto’s personal protégé Youn Chong Bak – but despite the churn, the firm managed to pull off two impressive feats, one of which was the aforementioned garmenting of the victorious footballers.

Suits in 120 stretch wool, youthful navy shirts, brogues. Two stars, signifying the nation’s two World Cup triumphs, embroidered and hidden in several spots — inside the jacket (over the heart), beneath the shirt collar, on the back of the tie.

A belt buckle in the shape of the Smalto “S” mark.

French coach Didier Deschamps had apparently requested the garments be “chic and sober” and was satisfied with the result. For his part, the then-president of Smalto, a man named Ludovic, was more than pleased to associate himself with a such fresh, cherub-cheeked bunch.

At the suits’ unveiling, he cited the team’s “unifying youth, which makes you dream.” He said Smalto, as a company, had the same mindset as star attacker Kylian MBappé (who had scored four goals in the World Cup at the age of 19, earning the Best Young Player Award and receiving a “welcome to the club” message on social media from Pele, the only other man ever to score multiple times as a teen at a World Cup).

And now for the other project, which was far less prominent or patriotic.

And yet it was practically unmissable, a projection so aggressively obeliscoid it might poke your eye out were you to view it from the wrong angle. That being the case, perhaps it actually was a most fitting symbol of the nation that birthed Gerard Depardieu.

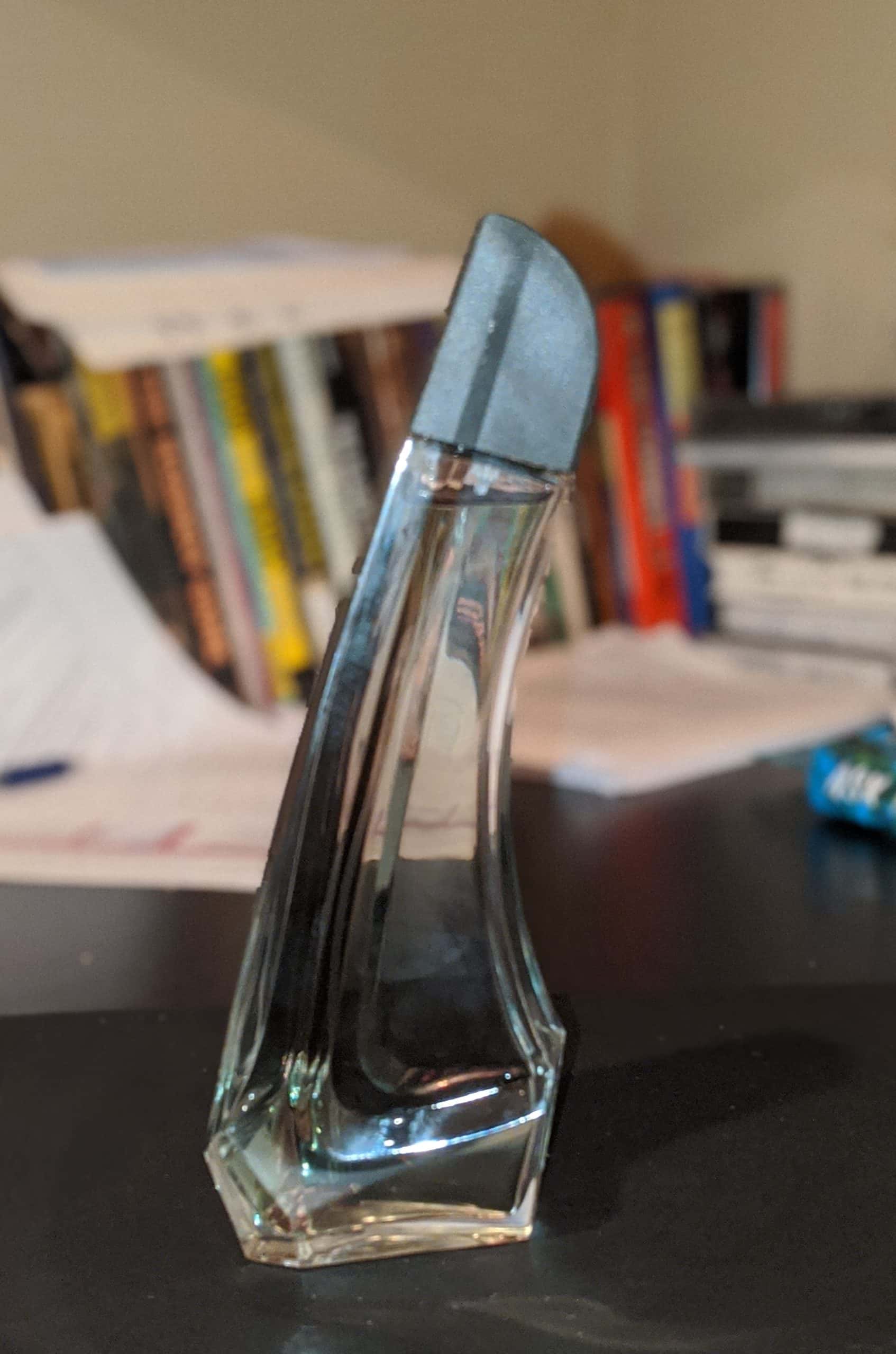

May I introduce you to FullChoke, the fourth and final scent ever released under the Smalto brand name, a product of 2004, though possessions of a similar proportion made out of wood are known to have been used by the women of ancient Greece (not a joke – see “Lysistrata” by Aristophanes).

I recognize it may be a bit unclear as to what the fragrance flacon is meant to resemble. So another photo, for the reader’s aide:

Here’s how things came to a head: For the last 20 years, a man named Dilesh Mehta, who studied electrical engineering at the University of Portsmouth, has been buying up licenses to produce fragrances under famous brand names.

A decade ago, he had under contract Agent Provocateur, Jean Louis Scherrer, Aigner Parfums and Worth. Then he bought Jean Pateau from Proctor & Gamble – no small feat considering the history of Pateau, which released its first scent in 1922.

Then five years ago, Mehta and a partner company, LUXE, bought the license to all Frederic Fekkai haircare products as well its seven salons.

Today, Dilesh Mehta’s Designer Parfums owns the licenses to the fragrances of Nicki Minaj, Jennifer Lopez, Formula 1 and Ariana Grande – that last name proving especially lucrative. By the end of 2017, Ariana scents were grossing more than $150 million globally.

True story: I was recently interviewing perfumer Frank Voelkl in his New York office, when I eyed beside me a grenade-shaped, shiny bottle. I quickly gabbed, “Oh, Flowerbomb,” in reference to the Viktor & Rolf bestseller that indeed is meant to resemble ordnance. Big mistake.

No, that’s Ari, Voelkl corrected me – and I can understand his displeased reaction: I was mislabeling perhaps the greatest commercial success of his career.

As for Formula 1, it revealed last December, at the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, its higher tier of three scents, which will retail inside futuristic 3D-printed containers for $10,000 a pop (a lower-priced line was meant to bow this summer but may have its release moved further back, given that racing season itself has been postponed).

Here, too, I’ve been fortunate to chat with the actual perfumer – Alienor Massenet did a couple of the new racing aromas and employed the note of narcissus in part because the late racer Ayrton Senna was as virile as men come but had a certain softness about him just the same. I met Alienor for drinks at the Park Lane Hotel in February, when she was in New York for business, before the world went mad.

Last I heard from her, via email, she said she was rushing to get the hell outta Paris before a quarantine came.

So all of this – the perfumery in the name of Pete Davidson’s ex, the bottles built for wealthy sheikhs, the Fekkai salons – is controlled by a dude name Dilesh with an electrical engineering degree. Whose corporate facility is located just south of UPS Watford, east of the Light of the Word Gospel Church, and caddy-corner to a Mini Cooper-devoted mechanics shop and a nursery school.

Just down the lane you can grab a bite at The Viking Fish & Chips or a joint called Indian Sizzler, which serves curry amidst “Miami Vice” décor, including turquoise and magenta mood-lighting.

Now let the storylines intersect – the company in a London suburb buying up perfume production licenses. A French men’s shop chosen to garb the national soccer team despite its namesake’s sex crime a quarter-century earlier.

It was the early Aughts and Dilesh, CEO of Designer Parfums, had acquired some years earlier the license to produce Smalto’s scents, which had previously been held by American firm Parlux. Now, keep in mind: These licenses give a company the power to manufacture and distribute the juice but not to make creative decisions in a bubble, without consultation of the brand’s workers. A certain level of collaboration is spelled out in the contract.

So it was that the small, nimble team assembled by Dilesh Mehta, including Navin Ullal, with whom I spoke on the phone for an hour earlier this week, had to respond to Smalto’s then-artistic director, who’d later lead Ungaro and his own eponymous scent line, Franck Boclet.

The year was 2004. The joint-development didn’t seem like it would be a problem in the least. And the first order of business wasn’t: What do we all want? How about a summery-yet-masculine fragrance? Sure, but who to make it? Why not tab Pierre Bourdon, perhaps the most accomplished and talented perfumer of his generation, author of Yves Saint Laurent’s Kouros, Creed’s Green Irish Tweed, Davidoff Cool Water?

No one could quibble at the selection, and once Bourdon agreed, the whole thing seemed a done deal. Sure, there would be the matters of marketing and logistics, involving bottles, ads, order volumes, distribution channels.

And it is sometimes the case that the perfumer doesn’t like the way his liquid is portrayed in magazine ads. There are times when the wrong country or facility is chosen for production (recessions and political upheavals affect even perfume). There are even quibbles about bottles (as told in my upcoming book on the world’s perfumers, the scent-masters behind Christian Dior’s failed Acqua di Gio competitor, Higher, attribute that capital-L to the steel-and-rubber rectangular receptacle in which marketing folks packaged it).

Yet the following disagreement, so far as I know, was unprecedented in the history of perfumery. And it’s possible it’ll never occur again.

Smalto’s director, Boclet, wanted the bottle to be a big glass dick.

Dilesh’s folks at Designer Parfums in Watford wondered why anyone would put Bourdon-made ambrosia in a penis. And I’ve smelt it – hell, that bottle pictured above is mine, snagged for 30 bucks from a dealer who could have priced it 10-times higher but maybe didn’t know any better and maybe wanted its presence gone at any cost – it’s a subtle, balanced, masculine marvel. Melony and tropical without being the least bit sharp, shrill, cheap-smelling. Without headache-inducing sea notes or the coconut that can evoke sunscreen.

So I, too, wanted to know why Boclet desired such packaging (pun intended).

“The idea was that Smalto was an excessively male brand,” Boclet wrote to me in a WhatsApp exchange to which he kindly assented. “That it had to please women too …That the bottle must be sculptural, masculine and imaginative. Hence the idea of a phallic form.”

Later on:

“The goal was for it to be masculine and remarkable. So I actually gave the instruction to create a sort of 3rd-degree dildo.”

Here I should have probably asked him what a second-degree dildo was, but I didn’t want to interrupt the flow.

“I wanted the object to develop sensuality. Let it inspire people to something else, and I listened to women a lot at that time on what a Smalto perfume should have been.”

Wait, women wanted a dildo perfume? I didn’t know that.

“It came quite naturally, after 5 to 6 meetings.”

And what about the name, FullChoke, which is, of course, a reference to fellatio?

“The phallic name was quickly arrived at by women. They saw Smalto like that. So I decided to create an object that could be a dildo without being it. ‘Full choke’ is also a reference to eroticism.”

Straight up: I don’t buy the bit about his consultation with women, at all, though I appreciate his chatting with me quite sincerely. I hate to say it, but it sounds like a ‘70s producer saying, Of course, Linda Lovelace wanted do that “Deep Throat” scene.

My conversation with Mr. Boclet went on a bit longer, and we discussed his departure from Smalto and his later return (his second period went by without the creation of a scent, in part because the brand had no money to spend on new projects at the time).

To this day, the folks in Watford at Designer Parfums think the fragrance could have been a tremendous success if it had been enclosed in a different container. Boclet thinks Designer Parfums simply was too small a company to handle a highly popular product – the first six months of sales were quite good, but Designer Parfums couldn’t scale up production or distribution thereafter, he says – and by the way, the bottle won an award, according to Boclet. Which would be a laugh.

It’s actually true – the crystal cock was given a prize for artistic achievement, and the whole thing would be a laugh if it weren’t for oddly gorgeous abstract art-deco look it obtains from certain angles:

The Smalto logo on the rubber cap is where you’re supposed to depress the trigger, but it barely budges and the juice dribbles out embarrassingly. All of this is 100 percent real and true.

You remember when I quickly presumed the spherical perfume in Voelkl’s office was Flowerbomb instead of Ari?

Well, I made a similar mistake here – but was met with a rather constructive correction. “At least you didn’t have to worry about any clones,” I told Navin Ullal, who’d overseen the bottles’ involved fabrication – each penis had to be fire-polished 11 times so that each facet was perfectly smooth.

On the contrary, Ullal said. He was in China some years ago, when in a market of counterfeit luxury goods he actually saw a knock-off Smalto FullChoke bottle. The tell-tale giveaways were the roughness of its glass corners – it was quite possibly the world’s most dangerous vaginal-insertion-item beyond those sold by Goop – and its plastic cap instead of the Smalto-branded genuine rubber one.

For the fun of it, Navin told the retailer, Hey, this is fake – this cap’s plastic. The merchant was quick in his response, “No, no – the rubber cap was produced only for European markets. In Asia, we got plastic.”

This is where the story of the of most bizarre high-class perfume ever created ends – not in England, though its producers still live and work there, nor in Paris, where the country’s most fabled sports stars wore belt buckles identical in design to that on the bottle’s head, not even in New York, where I sit in semi-isolation gripping the thing, coaxing its reluctant, tropical-smelling contents onto my neck and wrists – but in a Chinese market, where an anonymous dealer tried push a copy of the Western original, even after the West forgot the product existed.

It’s the total inverse of our current calamity, whose viral replication is entirely involuntary (in two senses: we don’t want to spread the virus but neither does the virus, which isn’t alive or endowed with agency; it’s just a tiny bit of malware coded to copy itself); whose origin, rather than endpoint, is a Chinese market beyond the reach of the law (yes, peddling pangolin is perhaps a more immoral crime than IP theft, though the point here is narrative similarity not the ranking of criminal behavior); and whose final destination seems already to be the Western capitals long considered models of hygiene.

Yes, the perfume is a penis, but the penis should also have served as premonition: In a globalized world, whatever goes out – to the East or the West – can very easily return along the same route (#SupplyChainSchmeckle).

Surely, no one reading this is unaware of the fact – now. But will we not forget the lesson down the line? Don’t humans always?

Francesco Smalto was a pimp to a foreign government yet the championship French team wore duds literally tagged with his surname to a national award ceremony 24 years later.

It’s kinda like 9/11 – not the day, not even the days afterward, but months later, when the camaraderie, the good will to his fellow, which everyone seemed to feel in New York, began ebbing away. And the obviousness of our being in this sortie/struggle called “life” together was superseded by a million small disaffections. By the divisiveness native to humankind.

And that’s partly okay – those clefts, our territoriality: This is also the source of our species’ gorgeous individualism. But only to a point. And that point shouldn’t be Almost Armageddon, the moment our survival seems jeopardized very suddenly.

We’re all our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers. Yes, we have billions of siblings now (will someone ask Philip Rivers’ kids what this entails?). To the degree we’re doomed to forget it perhaps let’s savor it now and in the months ahead – it’s maybe the lone plus-side of devastation – maybe that’s the point here.

Or perhaps – despite the long, long odds – your recollection of the above dick pics will improve your fraternal or sororal performance, enhance its duration, spur you to push harder.

To quote Sean Connery on “Jeopardy”: “The penis mightier.”