-

Worldwide

WorldwideFiery First Faceoff Between Hitchens and Kambosos Jr.

Who doesn’t enjoy a little fire with their boxing face-offs? Richardson Hitchins and George Kambosos Jr. brought some heat in a fiery face-off tradition at the...

-

Australia

AustraliaWeekend Boxing Schedule: Keyshawn Davis Loses Title

The boxing schedule is packed this first weekend of June, and that’s a blessing since the weekend’s most anticipated fight featuring Keyshawn Davis isn’t taking place....

-

Boxing

BoxingVasiliy Lomachenko Makes Retirement Official

Vasiliy Lomachenko, arguably the best amateur boxer of all time and a current and former world champion, made official what had been rumored and expected for...

-

Boxing

BoxingCanelo Álvarez Wins. Bring On Bud Crawford

The good news: Canelo vs Scull is in the books, and fans can now look forward to a showdown between Terence “Bud” Crawford of Omaha, Nebraska,...

-

Boxing

BoxingCanelo vs Scull: Undisputed Super Middleweight Clash Prediction

When the calendar turns to Cinco de Mayo weekend, the boxing world turns its attention to its biggest star, Saúl “Canelo” Álvarez. On Saturday, May 3...

-

Boxing

BoxingWords Fly from Ryan Garcia, Bill Haney at Fatal Fury Presser

Nothing rolls off the tongue in boxing like this Friday’s “Fatal Fury: City of Wolves“ card from Times Square in New York City. Ring Magazine’s historic...

-

Worldwide

WorldwideBest Russian Boxers of All Time: The Definitive List

Russia has produced some of the best boxers in history, leaving an indelible mark on the sport. From the Soviet era to modern times, these athletes...

-

MMA

MMATop 10 Best Pound-for-Pound UFC Fighters of All Time (P4P All-Time Rankings)

The term “pound-for-pound” (P4P) is one of the most hotly debated in MMA. It transcends weight classes, aiming to answer one simple question: Who is the...

-

Boxing

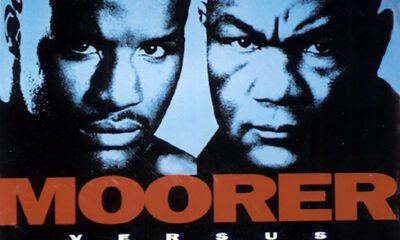

BoxingBig George Foreman Makes History: It Happened!

By 1991, former world heavyweight champion George Foreman’s comeback activity had slowed to one fight a year, sometimes twice. At his advanced age, after coming up...

-

Worldwide

WorldwideOmari Jones Making Boxing Moves in 2025

Super welterweight prospect Omari Jones of Orlando, Florida, is wasting no time getting back in the ring after his successful professional debut on March 15. Dressed...

-

Boxing

BoxingBig George Foreman: Return to the Ring For His Second Act

At 38 years of age and no longer looking the part of the villain in a suspense movie, Big George Foreman would return to the ring...

-

Australia

AustraliaRecap: Kambosos Jr. Holds Off Wyllie For Win; Brown Stuns Nicolson

George Kambosos Jr. seems headed for the title fight he wants against IBF Super Lightweight champion Richardson Hitchens after pushing back a determined Jake “The Machine”...

-

Boxing

BoxingBoxing Legend George Foreman Dead at Age 76

Charismatic boxing champion George Foreman died Friday at age 76. The news was posted via an announcement on Foreman’s official Instagram account early Friday evening. It...

-

Boxing

BoxingGennadiy Golovkin Leads Boxing’s Return to LA28 Olympics

Boxing will return to the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games, and much of the thanks goes to former world champion Gennadiy Golovkin. After years of uncertainty...

-

Australia

AustraliaIt’s About Time: Keith Thurman Returns March 12

After being out of the ring more than three years, former unified world champion Keith Thurman of Clearwater, Florida (30-1, 22 KOs) returns to face Australian...

-

Boxing

BoxingWhere the Fallout of The Last Crescendo Leaves the Heavyweight Division

Even with a couple of big names pulling out late, The Last Crescendo on February 22 in Riyadh made for quite the boxing spectacle. Headlined by...

-

Boxing

BoxingWhat’s Next for Dmitry Bivol Following Redemption Earning Victory Over Artur Beterbiev?

On February 23rd, Kyrgyz technician Dmitry Bivol secured his redemption as he outpointed now former undisputed light heavyweight champion Artur Beterbiev in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to...