Al Braverman’s ruggedly handsome face looked like a boxing glove that had been whacked with a bat. His nose was disenfranchised, not knowing which way to bend. He spoke in expletives and right up until his death at the age of 78 in July 1997, he was what used to be simply called “a boxing guy.”

He was portrayed by actor Ron Perlman in the 2017 film “Chuck,” which chronicled the exploits of Chuck Wepner, whose 1975 challenge of Muhammad Ali became the muse for Sylvester Stallone’s billion dollar “Rocky” franchise.

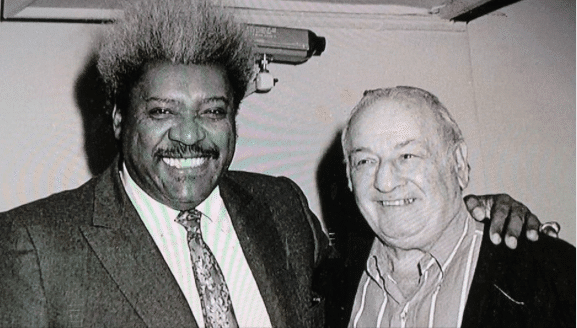

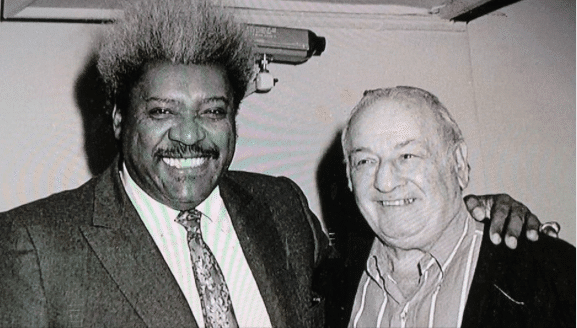

Braverman was a former fighter, manager, and trainer, but best known as a top aide to promoter Don King for whom Braverman went to work in 1975. As King’s director of boxing, Braverman negotiated contracts for his large stable of fighters.

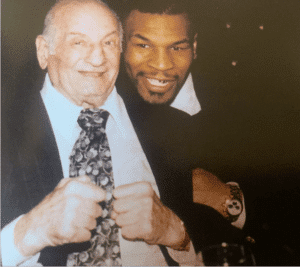

Don King with Big Al, who served as Don’s operations director for many years.

The late boxing sage Bert Sugar said Braverman “brought the mashed face and the mashed pronunciations into the 90s.”

At one time or another, Braverman managed or trained 30 fighters, including Carmen Basilio, Billy Bossio, Carlos Ortiz, Jimmy Dupree, Frankie DePaula, Mustafa Hamsho, and Wepner.

Before the Ali-Wepner fight, which Ali won in the 15th round, Braverman told reporters he had put a salve on Wepner’s face to stop him from bleeding. According to the New York Times, “no chemist had ever been able to completely break down the compound, Mr Braverman said with a straight face.”

“But, Al,” someone asked. “Won’t they complain about a foreign substance?”

“It ain’t a foreign substance,” deadpanned Braverman. “It’s made right here in the United States.”

Wepner was a notorious bleeder, who in 1970 required nearly 100 facial stitches after being stopped by Sonny Liston in the tenth round in Jersey City. Liston was asked after the fight if Wepner was the bravest opponent he had ever faced.

“No, but his manager is,” replied the stone-faced Liston.

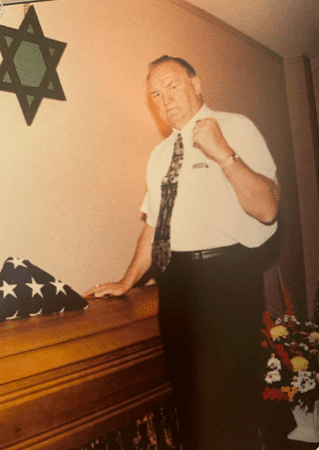

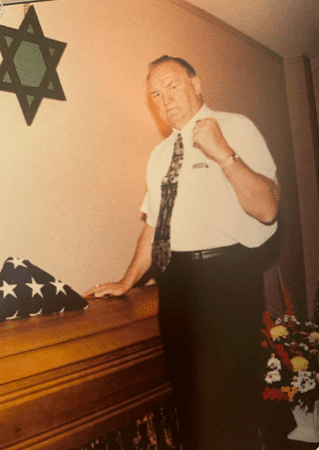

Wepner said goodbye to Braverman in 1997. Photo by Teddy B. Blackburn

Braverman had a brief career as a heavyweight, fighting and winning three times, with one knockout, in 1941. His pro debut was auspicious for reasons that were not so obvious.

“I was the only fighter in history who needed smelling salts before a fight,” admitted Braverman.

He recalled the bout at Laurel Gardens in New Jersey, a venue he described as “a real bucket of blood.” The promoter was Willy Gilzenberg and Braverman had come there with his trainer Ray Arcel.

Arcel instructed Braverman not to look at his opponent until he was in the ring. Braverman continually asked nagging questions, such as how many fights his opponent had. Arcel repeatedly answered, “Don’t worry. He’s new, like you.”

Suddenly, Braverman’s opponent vaulted the ropes to a thunderous applause from his legion of fans. Braverman turned to Arcel and said he would kill him.

Arcel told him to take it easy, the fans were just excited because of his unique ring entrance. Braverman started to feel faint, which resulted in Arcel busting smelling salts under his nose.

Braverman went on to win the fight, but railed at Arcel for the perceived deception.

Arcel defended himself by saying, “Al, if I told you the truth you would have jumped out of the ring.”

Braverman earned $15 for the night’s work.

After being drafted during World War II, Braverman was stationed at Camp Livingston in Louisiana. While serving as a boxing instructor, he said he challenged fellow soldier Joe Louis, the heavyweight champion of the world who was barnstorming the country doing exhibitions at military installations.

“Thank God he didn’t take it,” said Braverman. “I guess I was too unimportant for him, but I had a great reputation in the camp.”

While Braverman did receive one good conduct medal, he was also court-martialed five times. In one instance, he said he punched an officer who made an anti-Semitic remark.

“He said, ‘We’ll send this Jew to Eden,'” which Braverman described as “the hottest place in Cairo.”

Braverman knocked the officer out cold, which landed him in the O Ward, better known as “the nuthouse.” Braverman said the other inmates made sounds like roosters and read their bibles upside down.

Braverman was nicknamed Showers because, he said, “every time I wanted to hurt someone I took a shower instead.”

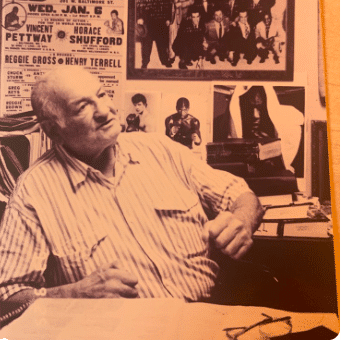

Al enjoyed a surge of attention when Sports Illustrated in 1975 shared his ability to turn a phrase in a colorful fashion.

Upon his discharge, Braverman immersed himself in the fight racket as a manager and trainer. He picked up the contract of a Coney Island lightweight named Pat Marcune, who soon complained about Braverman taking a third of his purses.

Marcune went to some mob friends to lean on Braverman, who refused to budge.

“I was a crazy Jew who defied everybody and Marcune was going to pay me no matter what,” said Braverman. “I even told them that I could shoot as straight if not straighter than them.”

There were few tricks that Braverman didn’t know or employ. Years later, in 1973, Wepner–and you can learn more about him here– was fighting Ernie Terrell. Terrell busted open Wepner’s ear, which had been injured in an earlier bout.

“Suddenly blood was everywhere,” recalled Braverman. “I started screaming at Chuck to jump on him because Terrell was cut. Terrell kept dabbing at his face looking for a cut and the tide changed. Wepner was like a madman and wound up winning a decision. Chuck used to cut himself worse shaving.”

The decision in Wepner’s favor set off a riot at the Atlantic City Convention Center after one of Terrell’s handlers charged the referee, Harold Valan, at the end of the bout.

In a 1980s publicity stunt, Braverman outfitted Mustafa Hamsho, who hailed from Syria, in Arabic garb at the height of the oil embargo.

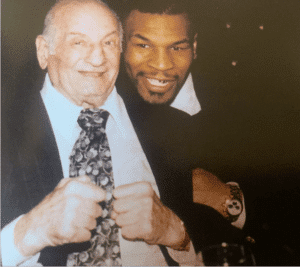

Tyson would have liked the Hamsho PR ploy. He respected Braverman as an OG. Photo by Teddy B. Blackburn

Braverman, who would have been considered old school in any era, said his biggest victory in life was against a man named Perez in an Irish tenement on Ninth Avenue in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen in 1948.

Braverman’s father owned a nearby pawn shop and had just turned away a drug addict trying to sell a stolen coat. According to Braverman, the man had murdered a woman while stealing the coat. Braverman saw a ruckus involving Perez and a detective named Terry Rogers. They were engaged in what Braverman described as “a life and death struggle” for the detective’s gun.

Braverman hit Perez with a left hook, but could not put him away. The dazed detective accidentally whacked Braverman in the head with a blackjack.

Braverman barely budged and the detective, realizing his mistake, yelled for him to put the handcuffs on Perez.

More than four decades later, Braverman still loved to show off the citation he received from Mayor William O’Dwyer, which he joked helped him get out of traffic tickets.

During his many years on the road, Braverman cultivated his passion for antiques by attending yard and barn sales throughout the country. At the time of his death, from complications of diabetes, he and his wife Renee owned the City East Antique Store on East 31st Street in Manhattan.

During one of my visits he was negotiating for Peter McNeeley to be Mike Tyson’s first opponent upon Tyson’s release from jail in 1995.

Al booked the first 23 fights for Tom McNeeley, the heavyweight, so he had a good sense of the son’s skill set.

He had trouble walking because of the diabetes, so he dispatched me across the street to get him a pastrami sandwich. I was under strict orders not to tell Renee about his culinary choice.

As I departed that day, the phone rang, which it did incessantly when you were in his company. I could hear him snarl into the receiver, “I’m doing everybody, what does it matter how the bleep I’m doing” before engaging in a discourse about an upcoming undercard.

Braverman was often described as Runyonesque, in deference to the colorful newspareman Damon Runyon, who wrote about hucksters and colorful rogues from the 1920s to the 1940s.

Perhaps the comparison should have been the other way around.