When you see a pal dealing with a stressful situation far beyond your control, and you want to help out just the same, so you ask: Hey, is there anything I could write about that might – in some minor way – help you cope?

(With an extended period of progeny-home-schooling, an overnight disappearance of cash and credit, a feeling of tremendous loneliness in a world without meet-ups and the healthful expurgation of negative thoughts they often facilitate. In a world sans stage plays and sports, theatrical exercises in projection that enable us to less fully occupy our actual situations.)

And he answers: You could write about what folks facing this sort of adversity did before us. So you do it, because you’re otherwise helpless – you’re no healthcare worker, no philanthropist. You’ve such a limited answer to daily life, let alone the perils and privations pertinent to existence now.

And you really love your buddy – to see him under such strain troubles you, almost as if your own lack of ideas is at fault. Love is well and good, but the moment calls for ingenuity, tirelessness, a measure of genius equal to compassion.

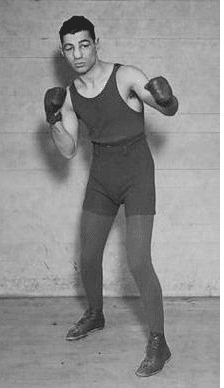

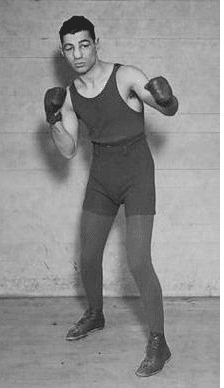

You have none of that, even while hopped up on dark chocolate-covered espresso beans. But, on the other hand, you do have Willie Jackson, a New Yorker of 100 years ago, who was born “Oscar Tobin” in the Bronx and served during World War I as a naval boxing instructor in that borough’s Pelham Bay training station.

Willie Jackson is a natural figure to bring up in this situation – and not because he shares a birthday with your mother, also a Jew from Pelham in the Bronx or because the lightweight’s flattened nose feels symbolic, perhaps encouraging – if there’s anyone who’s ever taken a punch, surely, it’s this mug, yet he stands before the camera clearly ready to battle on, bless his soul.

No, Willie Jackson is the man of the hour because he figures in the dual crises of the last world-changing pandemic period – 1918, when the Spanish Flu ravaged a globe already torn apart by World War I. Willie Jackson turned 21 in July of 1918 – he fought that year Rocky Kansas, Johnny Dundee, Lew Tendler – hall-of-famers all of them. In three years he’d face Freddie Welsh, another hall of famer. And his record features bouts against Portuguese Frankie Britt – whose cigarette-pack sports card pose has a kind of fiendish Tapia-Valero-Mayorga quality to it, as if he’s gleefully beckoning opponents to bash him on the kisser:

But back to Willie Jackson. Five days after his 21st birthday, in that Pandemic Year, he took on champion Benny Leonard in Madison Square Garden, in a full-on match whose purses were donated by the combatants to United States War Department’s Training Camp Activities Fund (Benny won, as you might expect from one of the greatest boxers in history and yet another hall-of-famer Jackson faced as a baby-faced midshipman).

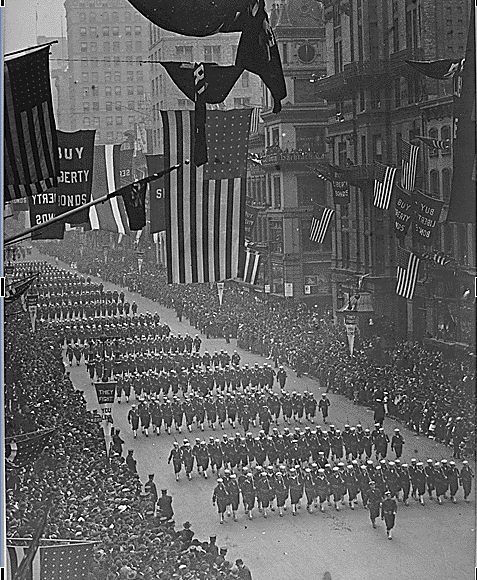

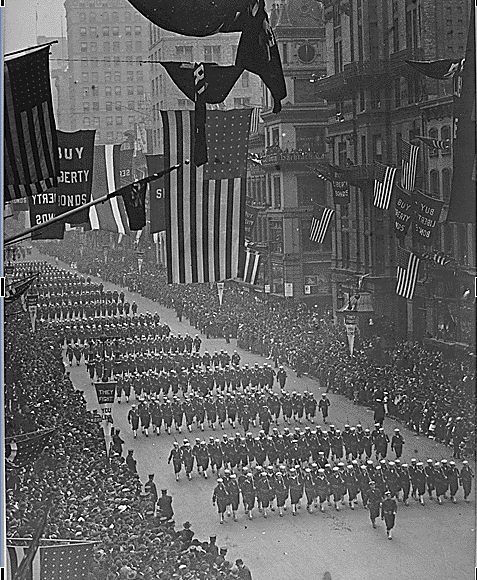

The sailors from Jackson’s base marching to raise money for the war effort, in the Fourth Liberty Loan Parade

Jackson boxed twice more that summer before the flu caught up to his naval base. It was September, and while the Navy had promised Jackson leave to get in some good work in the arenas of New York and possibly Philly and Boston that autumn, pandemic policy meant that everyone at his station was to be inoculated and kept at the base, away from the wider populace, for two weeks.

The astute reader might be at this juncture wondering how Willie Jackson was given a flu vaccine when the harmful germ wasn’t even identified as a virus for another two decades. The unfortunate answer is that he wasn’t: Pursuant to prevailing wisdom that influenza was a rod-shaped bacteria, he and the Navy jocks he taught how to fight were injected with inoculations against bacterial strains.

And while it might seem obvious that his base had no entertainment at its immediate disposal during this post-injection convalescence-lockdown beyond a phonograph or radio, the situation was actually darker than you might imagine – literally. One part of the US war effort at home involved conservation of resources – including the bituminous coal that powered electrical plants. In New York, the head of that effort was Walter Pamplin Moseley of Park Avenue – whose order was simple: No electric lights allowed after dark. None.

So to recap: Willie Jackson of the Navy fought Benny Leonard for no money, was then injected with bacteria despite their utter uselessness in the battle against a virus, was banned from leaving his base and forbidden from using any lighting after dark beyond a candle on it.

This would be a neat summary of his 1918 – if the war hadn’t ended on Nov. 11, after which he fought four times before the calendar changed, to make up for lost time – once in the Bronx, once upstate, once in Philly and once in Boston. One of the fights wasn’t scored, he won a newspaper decision in a second and ended the year with two sixth-round TKOs – in Boston, he knocked the opponent down thrice in the sixth. The last fight was on Christmas day.

Which is how you turn the page on a war and a pandemic – by coming out swinging, with all the energy you’ve had no choice but to hold in reserve. With a sort of cinematic expurgation of stress via big-stage socking. But Willie Jackson didn’t continue boxing professionally for long – he retired in 1922, after a reported 200 bouts, and became a paper dealer (#WorldsBestBoss).

He died 43 years later, in 1961. The last Life magazine he might have seen featured Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev on the cover with the caption: “Master of the Big Threat.”

This seems fitting, in the same way fuel conservation czar Walter Moseley’s eventual death due to the same type of pneumonia currently plaguing COVID patients is, to my mind. In an ideal world – free of pestilence and antipathy – I’d never so characterize an illness or passing.

But as the world faces a soulless pathogen, additionally riven by international argument, it can only benefit us to examine the past for similarities. To say aloud human strife is a sad constant. Our ability to fight five hall of famers and then hawk paper is our measure. To be dingers and then duffers, as the various decades demand.

That’s not to say context is the cure for our current anxiety – not for everyone, not for long for anyone. A veteran of The Great War dying as the Cold War heated up in the early ‘60s – that’s no solace to the presently bereaved, the suddenly jobless.

Perhaps it does nothing for the stressed and sad and uncertain. Those of us unnerved by the constant presence of kids and the absence of the institutions we’ve come to depend upon. The socially isolated. The justifiably fearful.

This snapshot may be very academic, for naught.

I know the Pelham military base gave way to the neighborhood my mom grew up in, I know a fighter became a paper salesman. The man who ordered us to turn off the lights ran banks till his lungs gave out as lungs sadly can do.

It can’t have been easy to fight Benny Leonard for no pay – or convince the Great White Way to unplug those glimmering marquees. It was done. Today is a great unknown – but so was yesterday.

I don’t know how encouraging that should be. But do I want you all to feel a little better?

Holy, hell, yes. All of youse. An entire effing regiment of readers. It kills me to see you sad.

The editor of this most especially.

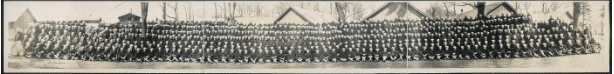

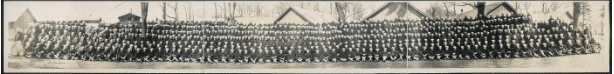

The first training regiment at Jackson’s Bronx naval base.