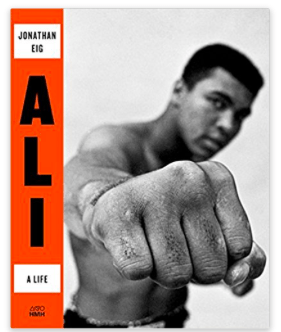

They will still be doing books on the man, ten, twenty, fifty, one hundred years from now. And it is understandable and proper; because Muhammad Ali was such a singular figure, such a different animal, that brainy sorts will want and need to appraise and re-appraise his legacy within every changed era.

Author Jonathan Eig is the latest examiner of The Greatest and his complex legacy. No, the pugilist-activist was not solely a master sports entertainer…Eig offers up ample evidence that Ali struggled to control his actions and appetites, within the realm of interactions with significant others especially. NYF grilled Eig and looked to get some insight into his process and what he learned about the only GOAT.

Q) Why another Ali book? What is there left to tell?

> This is the first complete, unauthorized biography of Ali. That’s reason number one for writing the book. But that’s not all. The timing was great. I was able to get FBI records on Ali, Elijah Muhammad, and Herbert Muhammad that weren’t available earlier. I was able to put Ali’s career and political stands in better historical perspective than would have been possible a generation ago. I was able to use new scientific data to track changes in his cognitive abilities caused by blows to the head. And I had access to key living sources, including three of Ali’s four wives, Don King, Gene Kilroy, Ferdie Pacheco, and more than 200 others I interviewed.

Q) And you came to this subject from where? Tell us your background…

> I’m a huge sports fan and a huge Ali fan. I had his poster on my ceiling as a kid. I did a little bit of sports journalism over the years, but mostly I made my living writing news and features. But when I moved to writing books, I wrote biographies of two of my biggest sporting heroes—Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson. I’m drawn to sports heroes who did more than play games, heroes who did great things off the field as well as on it. Ali fits that mold beautifully. This is the book I’ve been waiting my whole life to write.

Q) And you spent five years on this subject. Did you grow to be tired of him? Or were you able to sustain interest all the way through? And then, things changed when he died, yes?

> I never got tired of Ali. I could have kept working on this book for 20 years I don’t think I would have grown tired of him. I got mad at him sometimes. I became disappointed in his behavior sometimes. But he always remained interesting. He always presented a challenging puzzle. He was beautiful and beautifully complicated. When he died, my job got a little more difficult. For the first three years of my work, I had Ali to myself. No one else was sniffing around. No one else was harassing his friends and family for interviews. When he died, I suddenly had competition. And I felt compelled to hurry up and finish the book, but I didn’t want to cut any corners. I wanted this book to be as close to perfect as I could make it.

Q) I feel like a large part of the story was about the process…you had to chase Don King, who one might figure, since he likes to talk, but he was slippery. Ali’s bro wanted payment to talk to you. What are your thoughts on the hesitance of some to talk about the hallowed pugilistic deity, Ali?

> I wasn’t surprised that Ali’s friends and family wanted to be paid to cooperate with me. For the record, I didn’t pay anyone. But I understand. They hear I’m writing a book, they know I’m getting paid to write the book, and they figure they ought to get some dough for helping. That’s perfectly reasonable. And they don’t care if I say that journalistic ethics prevent me from paying. I wouldn’t care either if I were in their shoes. So I had to work harder. I had to call in favors. Gene Kilroy put his trust in me, and then he helped me get interviews with Ali’s brother, with Don King, with Louis Farrakhan. Same thing happened with Khalilah, Ali’s second wife. She needed time to decide if she could trust me. Luckily, I was in no hurry. And I was very persistent. Ask Khalilah. Sometimes I felt like I was courting her. One day she was falling for my charm, the next day she wasn’t. I sent her presents. I took her to dinner. I drove her around on errands. I have to say, I really enjoyed my time with all three of Ali’s wives. I can see why Ali loved them. They’re savvy and fun to be around.

Q) Ali gets brought up every day in many contexts–but one main one is what happens when fighters fight on too long. Manny Pacquiao, some are saying he should retire, but he tells us he still has the passion and wants to fight on. What is your stance on that, on fighters being able to have ultimate say on how long they fight?

> Sadly, I think there’s not much we can do about it, short of putting an end to boxing. The point of boxing is to cause concussions. It’s inherently dangerous, inherently unhealthy. Fighters are almost always going to go on too long. It’s not their fault, really. They’re good at fighting. They make good money fighting. People want to see them fight. And why stop once you’ve had success? Maybe we should put a cap on it. They get 30 pro fights and they’re done. Time’s up. But who’s going to enforce it? And who’s to say 30 is the magic number. In some cases, ten fights might be too many. Then there’s Archie Moore who fought more than 200 times as a pro. Who can say? As long as there’s boxing, boxers will decide their own fates.

Q) What one or two things did you find out and or come to comprehend about Ali that we the masses have gotten wrong?

> Here’s one: Ali’s grandfather was a convicted murderer. Not even Ali knew that. But I found the court records. The Cleveland Summit, that’s another good one. Legend has it that Jim Brown and Lew Alcindor and the other black sports stars gathered in Cleveland to show support for Ali in his refusal to serve in Vietnam. The true story was more interesting. Bob Arum asked Jim Brown to gather the athletes to convince Ali to make a deal with the U.S. government. The athletes were promised a cut of the action from the closed-circuit revenue on Ali’s fights. Only when they failed to persuade Ali to return to the ring did the athletes agree to issue a statement of support for Ali. I got the real story from Arum and confirmed it with men who attended the meeting. Another one: I think people have forgotten that Ali failed a drug test after his fight with Larry Holmes. Another one: Ali’s management team signed a secret contract with Liston’s managers before the first Liston fight; it guaranteed Liston a rematch. That doesn’t prove Liston threw the fight, but it does suggest he had one less reason to get off the stool after the sixth round. I could go on. I think even hardcore boxing fans are going to find new information in almost every chapter of the book. As Ali would say, It’s not bragging if you can back it up!

Q) Let’s play a what if. What if Ali were to come to prominence today, in this age. Would the chapters of his life unfold the same way? Or would this age of social media and mass narcissism and political correctness have caused an implosion?

> It’s impossible to imagine Ali in today’s sporting world. Look what the NFL is doing to Colin Kaepernick. What would they do to Ali? On the one hand, Ali would have loved social media. On the other hand, the media would have killed him for his extra-marital affairs. The media did kill him for his relationship with the Nation of Islam, which was perceived at the time as an anti-American hate group; but I think the attacks would have been even more brutal in today’s political environment. It’s interesting to think about, but it really is impossible to imagine. Boxers today don’t have the kind of star power than basketball players have, and that’s only one factor. Suffice to say there will never be another athlete like Ali.

Q) Please sum up the takeaways you want readers to have after reading your book.

> I want readers to see Ali a real man, not a legend. He was a brilliant boxer, a brave warrior for social justice, and one of the most delightful guys you’d ever hope to be around. He was also wildly inconsistent, stupid with his money, and unkind to many of the women in his life. He was neither all good nor all bad. Readers will be surprised to get to know the real Ali, but I think they’ll also be surprised to discover they love him even more once they get to know him and see him in all his complexity. There are a lot of important takeaways. Ali boxed too long, and that hurt him. He fought to show that black Americans could speak up and speak back without fear of retribution. He worked hard in his life after boxing to atone for what he perceived to be the grave sins of his youth, and in particular his treatment of women. Finally, there’s this: He was surprisingly—almost shockingly—humble. I know what you’re thinking—the greatest egotist of the twentieth century was humble? It seems absurd, but I think it’s true. Ali, for all his wealth, for all his beauty, for all his talent, never put himself above anyone else. He treated bus drivers and hotel chambermaids as well as he treated Saudi princes or Russian oligarchs. He truly loved people and enjoyed their company and never acted like he was better than anyone else. He said he was better than everybody else. He said he was the greatest of all time. We all know that. But when he was with you, alone, one on one, he never acted like he was superior. That’s a special kind of greatness.