Let’s be very clear: I understand the economic necessity of propping up the airline industry and many others in similar states of sudden near-insolvency. But not unlike Elizabeth Warren (a phrase I thought I’d never use in the context of a sports piece) I want certain preconditions attached to this aid.

Hey, Doug Parker, CEO of American Airlines: Your company wouldn’t refund my ticket to Milan for a perfume industry expo – despite the expo having been cancelled, the city (and its surrounding region of Lombardy) having been quarantined and locked down and the fact that I booked the ticket before medical authorities or governments took any of these unforeseeable, drastic measures.

You want my money by way of governmental grants and loans and the slush fund a man named Pence possibly maintains to muzzle past same-gender suitors?

Fine – but you gotta go 12 rounds with Andrew Golota, low blows permitted. Your future conveyances – in the air, on the sea, over land – must be populated with colicky babies and those travelers who eat curry from a Rubbermaid mid-trip.

Those JetBlue Terra chips? Start offering them – but also throw in some Garden of Eatin’ Blue Chips. And maybe those Tostitos baked with a basin in the middle for a neater salsa-dipping experience.

In the meantime, of course, none of us is going anywhere, and that seclusion, our various forms of self-isolation, will inevitably result in cabin fever, if it hasn’t already (still a better outcome than bodily fever).

But what if one could travel 1,000 miles without risking respiratory function – and, more over, do so in commemoration of a sporting event at a time when such playful pursuits are prohibited?

Vanessa will now be in your head for the duration of this pandemic. Sorry, not sorry.

About those miles, though: Let’s take it back to 1927 – the year the Murderers’ Row Yankees won the World Series (#DamnYankees) and Tunney beat Dempsey in their heavyweight championship rematch (and don’t give me BS about the long count – Tunney was a technician who took apart a brawler twice over; on balance, the result was fair; and if I seem defensive, it’s because Tunney was a literary sort who eventually taught at Yale – my kind of champion).

But 1927, that year of flapper-fundom, of pre-Crash parties in East Egg and West, featured a major sports event that was neither (boxing) sequel nor (baseball) fait accompli. Just the opposite: it was the very first edition of a competition that would be held thereafter for three straight decades:

The Mille Miglia – an Italian endurance road race of 1,000 miles (as the name indicates, though it was actually 1,005 in the first year) from Brescia to Rome and back to Brescia again – along a figure-eight route – without pause, each car helmed by two drivers.

Brescia, situated between Milan and Verona, which is to say, also in Lombardy, at the foot of the Alps, has been shut down for weeks now, in this bleak stretch of 2020. But back in March of 1927, the place was abuzz with 77 cocky young racers – plus all the wealthy locals who’d set up the contest (including Count Aymo Maggi – whose nobility didn’t stop him from entering and finishing sixth alongside a copilot named Maserati – yup, that Maserati – and journalist Giovanni Canestrini, whom I mention solely for the phonic fun his name affords).

And then there were the 5 million ordinary citizens who left their houses (not being bound to them by health edict) to line the course and glimpse their daredevil compatriots in the fastest machines of the day. Later, the race would see entrants from BMW, Mercedes and Porsche, but the debut run was an all-Italian affair – save for three Peugeots that crossed the finish line last (to be fair, some cars broke down and never even made it back).

There were Lancias, Alfa Romeos, Italas, Isottas, Fiats. A Bugatti Type 40. And three hot-rods from Officine Meccaniche, a company whose roots dated to 1903 but was primarily the result of a 1917 merger that made it Lombardy’s most important company. A producer of locomotives and train cars, tractors and agricultural equipment, big-rig trucks and, of course, erotic automobili.

Six years after the very first Mille Miglia, Fiat would buy OM, a recognition of its excellence that would nevertheless obscure its early accomplishments. OM cars won two Alps Cups races in 1922 and 1923. OM won its category in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1925 and 1926.

And then came the Mille Miglia of ’27 – whose entrance fee was a single lira. The top three finishers were all OM cars, including the winning #14 car of duo Minoia and Morandi, who finished in 21 hours, 4 minutes and 48 seconds. Or about the duration of a United flight from Newark to Baltimore.

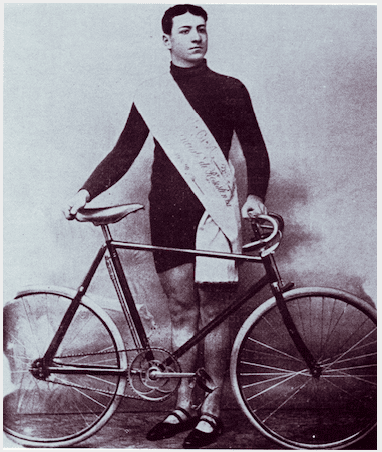

Gastone Brilli-Peri, meanwhile, a legendary cyclist and auto-racer both, led the pack through Rome in his Alfa only to see his rivals overtake him on the route back north when his oil pipe came loose at Spoleto.

One can’t mention the glory of the Mille Miglia without the inglorious reason it was halted after 30 years: the deaths of 56 people total, many spectators lined up to watch. Why the spectators could not have been positioned at a far-enough remove to watch the action without risking mortal injury I don’t understand (but I likewise can’t figure out why onlookers in neighboring France are allowed to run alongside and molest riders in the Tour de France).

But that first race remains this shimmering event in the sporting history of an Italian region now devastated by disease. Moreover, it augured yet another glorious moment the following year: You know the Olympic Lightweight Gold Medal – that auspicious trinket claimed over the years by Vasili Lomachenko, Oscar De La Hoya, Pernell Whitaker?

Well, a year after the first Mille Miglia in ‘27, at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, the lightweight gold was won by Carlo Orlandi – not only an Italian boxer but a native of Lombardy, a man from Milan, that city now under-siege, and a deaf-mute to boot.

A future European champ as a pro, Carlo Orlandi is easily one of the greatest underdog fighters the world has ever seen or ever will. Robbed of a sense crucial to athletics, unable to hear in a sport with auditory signals at every turn (from the opening bell to that aforementioned 10 count), he nevertheless beat an American for his medal in the finals and, according to Boxrec, retired with a pro record of 97-19-10.

I’m no virologist and the toll on Italy has already been immense in this dark time. And no amount of inspiration or moralizing will rid bodies of fatal foreign invaders. Still, I hope Italy, Lombardy most crucially, sees its share of miraculous underdog stories in the weeks ahead. Inexplicable, transcendent reversals of misfortune. Comebacks.

But I came here not to rally a distant people who will never read this (though if it should happen to reach an Anglophonic Italian, I’d be very humbled and I do sincerely wish my weak Knute Rockne “Gipper” attempt could effect change) but to deliver our stationary American cohort a kind of movement – those 1,000 miles about which Vanessa Carlton will forever – via YouTube and your memory – croon (which distance you cannot literally traverse at present but I promised you just the same).

And so I introduce you to Chopard 1927 Vintage, a fragrance composed by Bruno Jovanovic, which features an “asphalt” note, in celebration of that first Mille Miglia race. As gimmicky as it may sound, Chopard 1927 does indeed impart that smell of burnt rubber one gets when flooring a vehicle (that smell also happens to be on-trend again – go sniff the not-dissimilar rubber note of Prada Luna Rossa Black – a generation after Bvlgari Black introduced an intentionally outré rubber accord in 1996).

Chopard 1927 also has a riding jacket leather and some greenery – an olfactive equivalent of open-road motoring. It’s not the highest quality scent (owing to Chopard fragrances being produced on a limited budget by Coty), but I dare say it’s more movement and adventure than you’ll find supplied by any other 2.7-oz. container. And its steely gleam and solidity in-hand count for something in this stress-ball span.

Not that I’m here to sell anyone on anything – save for absolute immobility (and the small ways, via my personal, quirky likes, it can be made slightly more tolerable – maybe even adventurous).