Worldwide

Finally, Peace for Billy Collins Sr.

Published

on

By

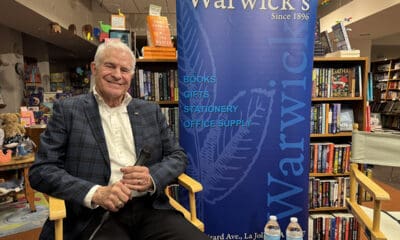

Randy Gordon

It was Wednesday, March 7, 1984.

I sat aboard an early-morning train from my home on Long Island to my office at Ring Magazine in New York City. I sat back in my seat and opened the Long Island newspaper, Newsday, to the most important part—the sports section. My eyes opened wide in shock and I sat transfixed and frozen for at least a minute as I read the small paragraph under a roundup of the day’s “other” stories, aside from spring training, the Knicks, the Nets, the Rangers, the Islanders and the NHL.

In bold, black letters the headline on the paragraph said it all:

Billy Collins Jr., 22, Dies in Car Crash

There were only a few sentences about young Collins and his death, but the headline said it all. I closed the paper and stared blankly out the window for the remainder of the one-hour ride into NYC’s Penn Station.

I left Penn Station in a jog, running across the street and up 31st Street to my office at Ring Magazine. It was a few minutes before 9:00 as I stepped off the elevator into my office, the one occupied 10 years earlier by Nat Fleischer and two years earlier by Bert Randolph Sugar.

My secretary, Jenny, walked in from her private office and said “Good morning, Randy.” Immediately, she realized something was wrong. Dreadfully wrong.

“What is it?” she asked.

I picked up the Newsday and turned to the page with the paragraph about Billy Collins Jr. I handed her the paper. Without saying anything, I pointed to the paragraph.

She gasped, clamping a hand over her mouth.

“I’m going to call Billy Collins Sr. at home,” I told her. “I need to offer my condolences.”

“Should I hold all your calls?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, almost in a whisper.

“I’m so sorry, Randy,” she said. She knew how close I was with Billy Jr.

When she turned to leave, I could see tears were already falling down her cheeks. She saw the same on my face. She pulled the door closed as she left.

I picked up the phone and dialed Billy Sr.’s number. I knew it by heart, having called his house so many times since the weekend of June 16, 1983, some nine months earlier. That’s the night Billy Jr. was savaged by the gloved fists of Luis Resto in Madison Square Garden. The unpadded, gloved fists of Luis Resto.

The phone rang once. Twice. I took a deep breath. On the third ring, Billy Sr. picked up the phone.

“Hello,” he answered in his raspy, Southern voice. “Billy, it’s Randy Gordon,” I said.

“Randy, my boy is dead,” he said, his voice breaking as he spoke the words. “They killed my boy. They killed my boy.”

He wasn’t referring to the alcohol-and-drug-fueled car crash which took his son’s life the day before in a Tennessee swamp. He was referring to the team of trainer Panama Lewis and fighter Luis Resto, who conspired to remove the horsehair padding from the knuckle areas of both of Resto’s gloves in the semi-final 10-rounder to Davey Moore’s title challenge against Roberto Duran in front of a packed Madison Square Garden crowd the night of Duran’s 32nd birthday.

As that fight took place, I sat on a plane, headed to Los Angeles, where, the following night, I would be calling a fight for the USA Network. When I landed, I picked up a pay phone to call my associate editor, Ben Sharav, back in New York, where it was a little after 3:00 a.m. I wanted to find out the result of the Duran-Moore fight, which Sharav filled me in on quickly. However, his focus was on the criminal assault which took place upon Billy Collins’ Jr.’s face for 10 rounds. He said, “You should have seen Collins’ face when he left the ring. He was beaten to a pulp!”

He knew I would be calling, and waited up for my call.

I told him, “Ben, I hate to do this to you, but you’ve got to get over to the hotel where the Collins’ are staying. They’re at the Southgate Towers, across the street from Madison Square Garden. They’ll be leaving the hotel no later than 9:00 a.m. so please try to be there no later than 7:00 am. If you don’t see them in the lobby by 7:30, call their room. They’ll be up. Tell them you want to shoot some photos of Billy’s face for a story I will write in The Ring.”

Sharav did what I asked him. And then some.

The photos he took of Collin’s swollen, battered and bruised face are etched among boxing’s worst, most horrific stories.

When I looked at the photos upon my return to New York on Monday, I was horrified. Sharav took the photos as the young unbeaten contender—the fight was declared a No Contest— stood against a wall, holding ice packs to his lumps, bumps, cuts, knots and bruises. He removed the ice packs to allow Sharav to get his shots.

Looking at the photos, I took a deep breath and said, “Nice job, Ben. Thank you for waking up so early with very little sleep and getting these shots.” I then added, “I only wish you had taken a few more of him with his eyes open.”

Sharav looked at his photos, then back at me. “They WERE open,” he said.

I felt my knees buckle.

Over the next few weeks, as the swelling subsided and eye specialists examined Billy Jr., they found he had irreparable tears in his iris and other damage. It was damage which would have kept him from ever being granted a license to box again. One day he was 14-0 and one of the hottest junior middleweight contenders on Earth. The Collins’ talked of championships and money. Lots of money, the kind of money Billy Sr. never made in a 38-17-1 (25 KO’s) career which went from 1958-1965. One day, Billy Jr. had all the promise in the world. The next day, he was an out-of-work prizefighter.

Drugs and alcohol became his best friend. His marriage to Andrea fell apart. So did the relationship with his parents. The more his life unravelled, the more he turned to booze and drugs.

One day, in the spring of 1983, Billy Jr. told his family he was going to the local lake to go fishing. Billy Sr. decided to go meet his son and fish with him. When he approached his son, he saw him laying face down in the grass, his head resting on his hands. He was crying. Hard. Loud. Billy Sr.’s heart broke, seeing his son like that. He lied down next to him and draped an arm over his son’s shoulder. Together, they cried. Hard. Loud.

I called Billy Jr. many times over the nine months between his fight with Resto and his tragic death. In the beginning, he sounded hopeful of making a return to boxing. As 1983 turned into 1984, he sounded unintelligible on the phone. He was always drunk. Hung over. High. It got worse.

He constantly argued with his wife and with his parents. Many times, he goaded his father— whom he had spent 21 years idolizing–into fist fights. Billy Sr., a rough, tough welterweight in his day, found himself swinging back at the son he adored. Many times, they bloodied each other.

Each phone call was painful to me. I had become friendly with both of them, announcing a few of Billy Jr.’s fights on ESPN, and often, going to dinner with them after the fight. The phone calls to Junior were painful because of how lost he was, and how fast he was falling into a deep dark abyss, one he’d never be able to escape from. The phone calls to Senior were just as painful. His wails of anguish and of utter devastation were long and loud, like the scene from Godfather III, where Michael Corleone, cradling the body of his fatally-wounded daughter, lets out the most emotion-filled scream ever seen or heard in the annals of theatre. Only, Michael Corleone’s scream of pain was performed by one of history’s greatest actors. With Billy Sr., the screams of a heart so-badly broken were not performed. They were the saddest sounds I have ever heard.

When Jenny left my office, I turned to write my editorial in The Ring. I entitled it, “Murder: Plain and Simple.” In the emptiness of my office, I cried as I wrote the editorial. It was the strongest piece I had ever written.

I ended it with this:

“If indeed there is a heaven, Billy Collins Jr. will spend eternity is paradise. As for his killers, the men I believe to be his killers. The Grim Reaper will come calling one day, and send them to burn in the fires of hell for the same amount of time.”

My editorial sparked many newspapers and sportswriters to take an interest in the story. Luis Resto and Panama Lewis were charged with assault, along with several other charges. They were put on trial in 1986. They were convicted. Resto was incarcerated until 1989. Lewis was in prison until 1990.

When I took office as Chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission in 1988, I received many calls of congratulation. One of them was from Billy Collins Sr. His thick Tennessee accent sounded even thicker and heavier. He had obviously been drinking.

“All the best in your new position,” said Billy Sr. “With you at the top and knowing all you know about the whole stinkin’ case, I have a much better chance of winning my lawsuit against New York State.”

He explained that he was suing everybody involved. Madison Square Garden. Promoter Top Rank. Luis Resto, Panama Lewis. His lawsuits against MSG and Top Rank were dismissed. He won his lawsuits against Lewis and Resto. Only, they had no money to their names. Finally, he was down to his last lawsuit. It was against the New York State Athletic Commission. As its Chairman, I had to take the stand.

“I’ll be sure to make a killing against the Athletic Commission,” he said, choking back tears and between gulps of whatever he was drinking.

“It’s the very least I should get because of what they did to my boy.”

I hoped the day would never come where I sat on the stand in the lawsuit “Collins vs New York State.”

In the hallways of the courtroom, Billy Sr. and I made eye contact. I smiled at him. He smiled back. His weathered face showed mileage. He was in his late ‘40’s, but looked much older. He looked at me at rubbed the thumb of one hand against his fingers of the same hand, as if to say, “I can feel the money I am going to make here.”

Deep inside, I wanted him to win. He deserved it. Nothing would bring his son back and no amount of money would change his life to the life he wished he could have led. But I knew the questions which would come at me, and I knew what I would say. I would do what I have always done. I would tell the truth. As we know, the truth often hurts. Sometimes, it hurts very badly.

Only a few months earlier, before I knew of the impending lawsuit, I called Billy as I often did. I was just checking in on him, trying to feed him something positive. What I got was a man in need of something much more than a friendly phone call from me. I heard the depth of depression.

“I don’t want to live any more,” Billy told me.

I assured him he did want to live. I told him he had to be a grandfather to Billy Jr.’s daughter.

“I have nothing left,” he said. “All I do is think of Billy Ray. I don’t want to die, but I don’t want to live, either. I don’t want to be here any more. Maybe I’ll just close my eyes tonight and not wake up. That’s what I want. Every morning, when I wake up, I start crying. I don’t want the pain any more. I don’t want to live.”

If he wanted to live, it was for one more thing—his lawsuit against The New York State Athletic Commission. A few weeks before the lawsuit, I called Billy. I did so to let him know that no matter what happened in the lawsuit, I was his friend. I called him with several members of my staff in my office. I didn’t want it coming out that I had conspired with or discussed the case with him.

“I’m not suing you, Randy,” said Billy. “I’m suing the State of New York.”

“I know that, Billy,” I said. “Billy Ray would have been a champ. He would have made a lot of money for his family. I want the money I will be awarded from this lawsuit to go to his family. It’s the least I can do.” Then he did what he did more often than not when we were on the phone. He cried.

** *

When Billy Collins Sr. took the stand, he told the jury that his son was undefeated and the best junior middleweight on the planet. He said championships. Commercials and endorsements— along with tens of millions of dollars—awaited his son. The jury listened intently. He blamed the negligence and unprofessional attitude of the New York State Athletic Commission for his son’s death.

“Had there been an Commission Inspector in that room, the gloves never could have been tampered with,” said a teary Collins Sr. Some members of the jury wept as he told the story of how depression engulfed his son following his beating at the hands of Resto.

“A man can be mugged on the street at any time and any place,” said Collins Sr. “But my boy’s mugging took place right in Madison Square Garden, where the New York State Athletic Commission allowed it to go on. My son was the best fighter in the world. Nobody could have beaten him. It took cheating and the ineffectiveness of the New York State Athletic Commission to beat him.”

I sat in my seat. I didn’t cringe. I didn’t squirm. I just listened, I listened and I secretly hoped the jury would rule in Collins’ favor.

Then, I was called to the stand, which I walked to with confidence. I looked like the Commissioner, dressed impeccably in a dark suit and a sharp, light-colored tie. The Court Officer told me to raise my right hand as he asked, “Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help you, G-d.”

“I do,” I said.

“You may be seated,” said the Court Officer.

I looked at the table where Billy Collins sat with his attorney. Billy’s widow, and her family, sat behind them. A judgement against the New York State Athletic Commission would have most likely meant a very large cash settlement for the entire Collins family. Billy smiled at me. It was obvious he thought I was on his side. The fact is, I was on no side, except the side of the truth. I smiled back at Billy, though. We were friends. His attorney rose from his seat and approached me.

“Commissioner, is it true that you announced a few of Billy Collins Jr.’s fights pn television?” asked the attorney.

“That is correct.” I said “I announced them on ESPN.”

“And isn’t it also correct that you were present to watch Billy Collins train in the gym on many occasions when he came to New York?” asked the attorney.

“That is also true,” I said.

“You thought he had quite a lot of boxing talent, didn’t you, Commissioner” he asked. “Yes, sir, I did,” was my reply.

“Would you say he could have potentially earned millions of dollars?” asked the attorney. “Well, it depended on who he fought,” I responded.

“But the potential was there for him to earn millions of dollars, wasn’t it?” I was asked.

“Well, technically…” I started, then was cut off.

“Technically, he could have earned millions of dollars, isn’t that right, Commissioner. All I need is a ‘Yes’ or ‘No.’”

I replied, “Yes.”

“I have no further questions,” said Collins’ attorney. He returned to his seat. I watched Billy Sr. give him a pat on his thigh as he sat down.

The attorney for the New York State Athletic Commission rose from his seat and approached me.

“Commissioner, what weight did Billy Collins Jr. fight at?” asked the Commission’s attorney.

“He fought at 154 pounds,” I replied. “The weight is referred to as the junior middleweight class.”

“In your opinion, Commissioner, was Billy Collins Jr. the best fighter in his weight class?” I was asked. I looked straight at my attorney. He was standing directly in front of Billy Sr. I saw Sr. lean forward as he awaited my answer. I took a deep breath, then paused.

My attorney, sensing I was struggling in answering his question, asked it again.

“In your opinion, Commissioner, was Billy Collins Jr. the best fighter in his weight class?” I shook my head. “No, he wasn’t,” I said.

“CONJECTURE! Your Honor,” shot Collins’ attorney. “Who is Commissioner Gordon to say Billy Collins Jr. was not the best at his weight class?”

The judge nodded and turned his attention to me.

“Fair objection,” replied his Honor. “You regulate a state agency. Earlier, you said you announced a few of Billy Collins’ fights. But what gives you the qualification to make such a bold statement as you just did?”

I turned to the judge and replied.

“At the time Billy Collins was fighting,” I said, “I was the Editor-in-Chief of Ring Magazine, the oldest and largest boxing magazine in the world. It was my job, as well as my passion, to know more about boxers than any person in the world. I watched Billy Collins fight. As I said, I announced several of his fights. Others I saw from my seat on press row.”

“Commissioner Gordon is probably more qualified than anybody to speak on this subject,” said the Commission’s attorney.

As he said those words, I watched the distress on the face of Billy Collins Sr., and on the face of his attorney.

“I have no further questions,” said my attorney, who then returned to his seat at the table. Then, Collins’ attorney said, “I have one further question.”

The judge motioned him to step forward and proceed.

“Commissioner, in a fighter’s dressing room. Are there members of the Commission who watch a fighter have his hands wrapped and who stay with the gloves which are to be used?”

I said, “There are. They are called inspectors.”

He continued.

“Isn’t it true, Commissioner, that these inspectors are not allowed to leave the dressing room, that they must stay with the fighter throughout his hand-wrapping and gloving up?”

“This is very true,” I replied.

“And isn’t it true, Commissioner,” he continued, that an inspector must stay with the gloves right up until the time they are placed on the fighter’s hands?”

“This also is true,” I said.

“Is it true, Commissioner,” came another question, “That, in your rulebook, it states that, and I quote, ‘An Inspector—or other approved Commission member—shall remain be in control of the bout- approved gloves at all times?’”

“This is very true,” I answered. I also knew where he was going. I knew what his next question would be. I was right.

“Then why was there no inspector or member of the Commission in the room when Luis Resto was wrapped and gloved. Why was no member of the Commission in control of the gloves?”

The quiet courtroom grew ever quieter. All eyes in the packed lower Manhattan courtroom were on me.

“The reason there was no inspector in the dressing room, the reason the gloves were left in the hands of Resto’s cornermen,” I stated clearly, “is that there was no rule in place in 1983 that any Commission member ‘babysit’ sit the gloves. In boxing, certainly in New York, the rule of an inspector being mandatory didn’t come into effect until after the night of June 16, 1983. In essence, it became the ‘Billy Collins Rule.’ Today, inspectors watch every move a fighter and his camp makes in the dressing room. Back then, there was no rule in place. That’s why Resto’s gloves were tampered with.”

Collins’ attorney froze. He just saw his client’s case implode.

“I have no further questions,” he said. He returned to his seat. There was no more smile on Collins Sr’s face as he looked at me. The smile was replaced by an angry glare.

The commission attorney rose and said he had one more question. The judge nodded for him to ask his question.

“Commissioner, thank you for explaining about the rule that exists now, but didn’t exist in 1983. If this tragedy had happened today, under today’s rules, would you say the Commission would be to blame for such an incident.”

“Most definitely,” I replied.

“But, with no such rule in effect in 1983, do you think the Commission should be held at fault for the incident?” asked the attorney.

I shook my head.

“No rule or rules were broken,” I said. “There was no such rule in effect. How can the Commission be held for negligence when no rule whatsoever was broken? If it happened today, absolutely. In 1983, absolutely not.”

My attorney rested his case. The jury heard what they needed to hear. They needed less than an hour to come up with their verdict. The New York State Athletic Commission was not liable in the case of Collins v New York State.

I remember being without expression when the judgement of the jury was announced. I wasn’t happy that my agency won, and I was unhappy that the Collins family didn’t win.

They didn’t win because of my testimony. But what was I supposed to do? Was I supposed to lie to the jury? Lie to the court? Lie to the world? Lie to myself? I didn’t think Billy Collins could have ever beaten Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns, Roberto Duran, Tony Ayala and others, and I said so. I believed that. The jury believed my words, as well. I still believe how I felt and what I said.

I looked at Billy Collins when the verdict was read. He glared at me. Daggers were being thrown at me through his eyes. Then, he leaned over and put his put his head in his hands and he wept. For me, it was so painful to see. I had just broken his already his irreparably-broken heart even more. It was probably the most painful moment of my life.

While heart-wrentchingly sad, I began to walk over to Billy. I didn’t know what I would say, but I wanted to go up to him. Maybe I’d just sit next to him and put an arm around him. Maybe I would just say, “I’m sorry.”

As I walked towards him, a hand on my shoulder stopped me. It was my attorney. He knew how I felt. He knew how emotionally wrapped in the case I was. He knew that, deep inside, I wanted Billy to win the case. He also knew it was pointless for me to walk over to Billy. He led me out of the courtroom.

On the way out, I passed Billy’s attorney.

“For what it’s worth, tell Billy I am very sorry this didn’t turn out the way I wanted it to.” He just looked at me and said nothing. Then he turned away.

Over the years, I attempted to call Billy several times. My voice messages were never returned. On one of the two occasions he picked up and heard it was me, he hung up. On another of those occasions, he spoke briefly.

“How can you call me?” He asked. He sounded drunk. “How can I ever talk to you after what you did to me on that stand? Goodbye!” He hung up.

Following the final failed lawsuit, Billy Collins retreated into his world of depression, darkness and isolation.

In 2009, producer Eric Drath put together a documentary entitled “Assault in the Ring,” which was shown on ESPN’s “30 for 30.” For the documentary, Drath went to Antioch, Tennessee and tried to get Billy Sr. to speak on camera.

Billy left Drath standing at the closed front door of his home, yelling “GO AWAY!” to Drath. You can watch the documentary, which won an Emmy Award, on YouTube.

On Wednesday, January 9, 2018, Billy Collins Sr. passed away at the age of 80.

Remember the paragraph you read earlier, the one I told you I wrote in my editorial in The Ring the day I found out Billy Jr. had died? Well, I can now update it:

“If indeed there is a Heaven, Billy Collins Sr. is there. The hole in his heart is gone, and he is free of the pain, grief and anguish which had tortured him for the last 34 years. He is with Billy Jr. once again, where they will spend eternity in paradise.”

Together.

IBHOF Class of 2025 Inductee, former Chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission, former Editor-in Chief, RING Magazine, and co-host along with Gerry Cooney of SiriusXM's "At the Fights." The Commish is the ultimate New York-based boxing insider.

You may like

-

It Happened: Jim Lampley’s New Book Covers His Wide World Of Sports

-

King Ryan Garcia Returns, The Rest Want The Crown

-

Congrats To 4 NYFIGHTS Contributors Who Won Awards in BWAA Writing Contest

-

The Ring Magazine Closes Up Shop

-

Heather Hardy Gets The Win

-

130-Pound History: Oscar Valdez-Shakur Stevenson Fight Week