Whose life has been as well covered as Muhammad Ali’s? Do we really need another Muhammad Ali book, film, documentary, or anything?

Many have been asking that question since the announcement that Ken Burns was to deliver what would become a four-part, eight-hour docuseries on the incomparable boxer. As great as Burns is, asking “is this necessary?” makes some sense. After watching Burns’ series myself, I think it’s fair to say that no previous works have been as comprehensive as this one.

There’s a reason for this, though. Pick any five years of Ali’s career, and there’s a movie in and of itself. From his 1960 gold medal victory in the light heavyweight division at the Olympics in Rome, to his sad final defeat at the gloves of Trevor Berbick in 1981, Ali’s life wasn’t just one movie—it was several. Any film or project that tries to add up all the contradictions and complexities of Muhammad Ali (even one as exceptional as Michael Mann’s “Ali”) is likely to come up short.

For such a grand life, you need a grand number of hours, and that’s what Ken Burns was allowed here. I suspect the subject lent Burns plenty of inspiration, but the filmmaker deserves credit for making the most of it.

Round 1: The Greatest (1942-1964)

Burns’ strength as a documentarian has always been in assembly—he is an extraordinary organizer of facts and images. That gift has, at times, been a creative drawback, making some of his work staid and predictable. Burns’ “Muhammad Ali” is the opposite of those two descriptors. It is electric right from the jump, full of exquisite detail, and dynamic in its delivery of facts, photos, and footage.

The first episode presents us with Cassius Clay, a young black man from Louisville, Kentucky, who tries to mitigate his dyslexia by playing the class clown: what his eyes couldn’t read, his mouth could make up for. Ali began talking before the age of one—he was a natural born promoter—but underneath that bravado was a young man haunted by the ghost of Emmett Till, and fully aware of his own “unforgivable blackness.”

We learn of Ali’s wayward father and resilient mother, and of Ali’s stumble into boxing. Remarkably and unconventionally skilled at a young age, Clay quickly became a top amateur and earned his way onto the US Olympic team for the 1960 games in Rome, Italy. It’s hard to believe that a man who would one day have an airport named after him was afraid of flying, but it was the flight to Rome that was most likely Ali’s greatest opponent. Once there, he was so clearly dominant that turning pro was a fait accompli.

No one had ever seen a heavyweight move like he did, punch with such alacrity, and fight with such originality in the heavyweight class. His boxing was magical and inexplicable: just like Jimi Hendrix’s guitar playing, if you tuned your instrument the exact same way and played the same notes, you could still not reproduce the same sound and fury.

The young boxer’s conversion to Islam as well as his significance as a figure in the battle for civil rights is shown to be gradual—the early Clay is brash, and mostly about self—however, in the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam’s most dynamic speaker (Malcolm X), Clay found not only purpose, but a name.

When Clay beat the bully Sonny Liston (whose life, Burns practically argues, deserves a documentary of its own), he took the name Muhammad Ali, extinguishing what he would call his “slave name” and signifying the start of an extraordinary period in American history where he would become the most polarizing figure in the country and the linchpin upon which an entire movement would turn.

The episode closes with Beyoncé’s “Freedom”—a needle drop you never see coming, but sure feels right when it hits you. And freedom is exactly what Ali would spend the next six years of his life fighting for.

Round 2: What’s My Name? (1964-1970)

The tone of episode two is notably different than that of its predecessor. The vibrant nature of Cassius Clay is replaced by a no less defiant, but an almost demure Muhammad Ali after joining the Nation of Islam. It’s in this episode that we see the beginnings of Ali as a world figure. His tour of Africa in the ‘60s prefaced his “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman nearly a decade later, and we see the beginnings of his most perilous bout of all—with the United States government over the military draft and his refusal to serve in Vietnam. During this period, it wasn’t just Ali against his next in-ring opponent, it was Ali against the most powerful nation in the world.

While Ali may have been widely unpopular in America, Burns shows us that other countries took a different view. In London, where Ali was once seen as a villain, he is greeted like a conquering hero. They knew he was right to oppose the Vietnam War before we did. Of course, he knew it before we all did.

Burns shows the growing significance of Muhammad Ali within the Civil Rights movement during a filmed press conference with Ali and Martin Luther King Jr.

Here was an athlete who struggled with spelling and basic math standing next to the greatest orator of the 20th century and eclipsing him in stature both physical and figurative—Ali owned the room no matter who was in it.

After dispatching Liston a second time (in a fight whose knockout ending will be debated forever), Ali turns his focus to Floyd Patterson (the heavyweight champion who Liston demolished before taking on Ali twice). Patterson, who refused to call Ali by his name, referred to him as “Cassius Clay” whenever possible. This was a huge mistake. Already on the downside of his career, Patterson was brutally punished by Ali in the ring in a cruel display of boxing prowess that left Patterson completely decimated by the end of the fight.

Boxing is a sport that requires a certain amount of cruelty to be any good—inside the ring is where one man tries to take another man’s head off. What Ali did to Patterson was far more harsh. Ali carried his opponent through the fight, refusing to knock him out when the opportunity arose so he could keep hurting him. To Burns’ credit, he doesn’t shy away from this part of Ali’s nature. Instead he gives us a full picture of a man who was capable of great kindness and also a 2 that knew few bounds when he thought it served him.

Ali would fight two more times before having his boxing license taken away: once against Cleveland Williams, in a performance so masterful that left future heavyweight champion Michael Bentt, a secret weapon in this docuseries, in awe. As Bentt points out, Ali lands a ten-punch combination against Williams’ head while Ali is going backwards. It’s a level of artistry that had never been seen before in boxing. No one—in any weight class—does that.

Ali would then face the 6 foot 6 Ernie Terrell, who held the heavyweight belt that had been stripped from Ali due to his defiance of the draft. Terrell, like Patterson, refused to call Ali by his chosen name, and like Patterson, he would pay a terrible price.

“What’s my name?” Ali shouts—you can hear it in the footage—throughout his fight with Terrell as he pummels him from all angles and directions. Again, Ali would carry an opponent deep into a fight just so he could keep on hitting him.

Post-fight, sportswriters called Ali mean, malicious, and barbarous. What they (and Terrell) should have called him was Muhammad Ali.

When Ali officially refused to accept his draft status, he was stripped of all of his belts, his passport, and the right to box in the United States. In order to make ends meet, Ali did speaking tours, visiting colleges both majority white and majority black. Remarkably, he changed his tone for no one. Even more incredibly, both audiences rallied around him—black radicals and white hippies found themselves joined in opposition to the war and in support of its greatest opposer.

As episode two closes, we see a heavier, slower Ali vanquish a lesser opponent with more effort than one would expect. His three and a half year exile would cost him more than dollars, as the great sportswriter Budd Schulberg would point out after his return fight, it would also cost him “a step.” A fact that would turn out to be the greatest price he would have to pay as his career wore on.

Round 3: The Rivalry (1970-1974)

Focusing mostly on the rivalry between Ali and Joe Frazier, Episode 3 shows us an Ali that returned to the ring a slower, more hittable version of himself. As his fight doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, would say, Ali “found out he could take a punch.” That’s something that would serve him well in one regard, but painfully less so in another.

While Burns is focused, of course, mostly on the life of his main subject, he spends more time than one might expect on detailing the lives of his opponents. This is true especially of his treatment of Joe Frazier—a man who grew up in the cotton fields of South Carolina, discovered boxing while working at a Detroit slaughterhouse, and perfected his forward-first style in the sweaty gyms of Philadelphia. Joe Frazier lived the hard-knock life of a Jim Crow era black man, and Burns doesn’t miss on depicting that truth.

Ali, however, would use race-baiting language when addressing Frazier and promoting the fight, and at least half of America ate it up—treatment that (Burns’ series makes clear) Frazier did not deserve.

In many ways, the two were made for each other. Ali was loud, Joe was quiet, Ali was a boxer, Joe was a slugger. Ali fought the world, Frazier fought the man in front of him. Styles make fights they say, but contrasts make rivalries.

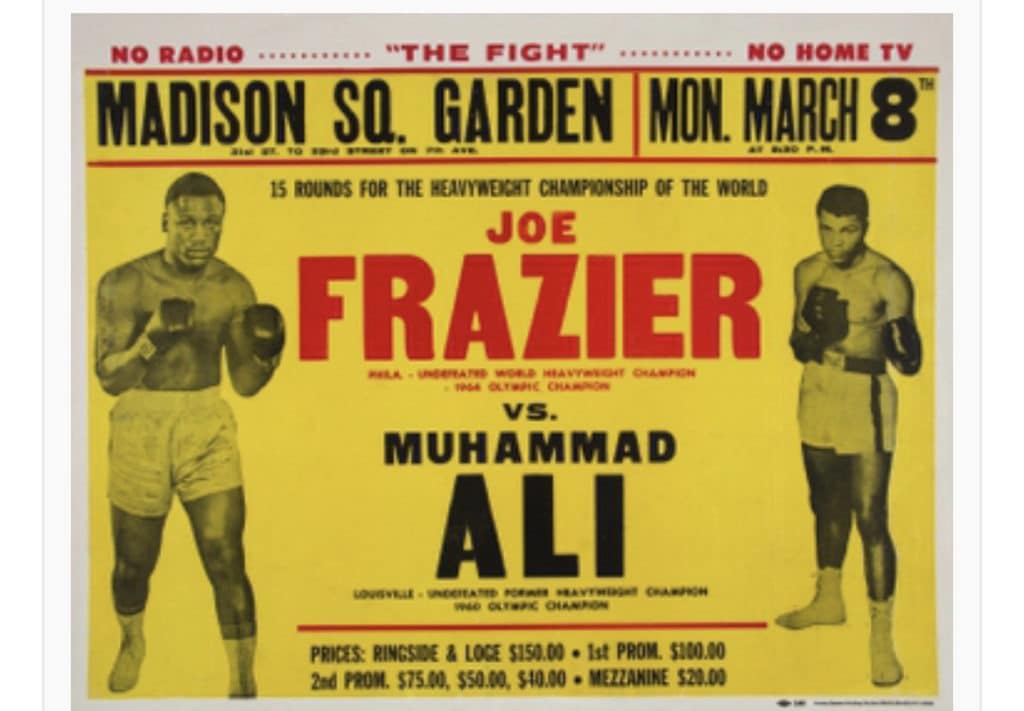

When they met in the ring, it was truly a one-of-a-kind event: two undefeated champions, two Olympic gold medalists, with the whole world watching on television and the most famous celebrities in attendance. The “Fight of the Century” lived up to its billing, but the winner would be Joe Frazier.

As I wrote earlier, Ken Burns is an expert in assemblage. Memories may fade, but a document such as this becomes a great source of reference. Even after the Frazier bout, Ali’s fight with the government was not over—a fact I had forgotten.

Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice, had to recuse himself from Ali’s case (as he had been the solicitor general at the time of Ali’s conviction) and the decision on Ali’s claim as a conscientious objector would be left to eight old white men. In the end, the court ruled in his favor not based on the merits of his claim, but because of a technicality. Ali had not received due process in his original claim within the state of Kentucky. Raise your hand if you knew this.

When Ali/Frazier 2 finally came together (a full three years after their first fight), both men were diminished. Still, their rivalry held the nation in its grip.

There may have been no belt at stake when they fought a second time, but the future of both men was very much on the line. As the excellent modern sportswriter Howard Bryant points out in the series, “You have to have real competition to prove your greatness.”

Ali and Frazier had each other.

Round 4: The Spell Remains (1974-2016)

The fourth and final episode of Muhammad Ali is quite naturally elegiac. Ali is proven prescient about Vietnam, but his vulnerabilities inside and outside of the ring are laid bare. He’s not the man he used to be, and the ever dangerous George Foreman is waiting in the wings.

Burns wisely doesn’t compete with the definitive documentary on the Ali/Foreman fight, the glorious Oscar winner “When We Were Kings.” Instead, he briskly covers the bout, focusing primarily on Ali’s head games with Foreman and his strategic mastery of the contest by creating the counterintuitive “rope-a-dope” defense. When Foreman hit the canvas in the eighth, Ali reclaimed his crown—a full seven years after his return to boxing.

This is the sort of context that Burns gives the film. The way we remember things isn’t necessarily the way they happened. In retrospect, what may have seemed preordained was most certainly not. In Burns’ telling, the arduous nature of Ali’s journey is clear: none of this was a sure thing.

Instead of retiring after the Foreman fight, Ali turned to his nemesis Joe Frazier for a third and final time in a bout dubbed “The Thrilla in Manilla.” Outside the ring, Ali returned to his race-based jeering of Frazier, most painfully referring to Joe as a “gorilla.” It’s safe to say both men held the other in contempt. Sportswriter Jerri Izenberg poetically states that belts and records didn’t matter to Ali and Frazier when they were in the ring together. The two men were fighting for “the world championship of each other.”

It would be a brutal fight that would take too much from both victor and loser. The slow motion sequence Burns uses in focusing on the 14th round of the fight is both terrifying and illuminating. As Ali rains punches down on Frazier’s head, we see the full damage of the blows. It’s the type of boxing footage that makes you think, “why in the hell would anyone do this?” Frazier’s trainer Eddie Futch boldly (and correctly) stops the fight after the 14th, possibly adding years onto both men’s lives.

The rest of Burns’ final episode is the most moving. Ali loses to the unheralded Leon Spinks, regains his title a third time, and carries on boxing far longer than he should have. Not only are his feet slower, but so are his hands, and more significantly, so is his speech.

In every way, Ali is well past his prime and on a downward slope. Humiliating losses to former sparring partner Larry Holmes, and Trevor Berbick follow. When Ali finally retires, his post-boxing life is not spent deservedly enjoying the spoils of an extraordinary career, but rather battling Parkinson’s—the insidious disease that robbed this man, fleet of foot and tongue, of movement and speech, but not his spirit nor soul.

While Ali was not able to conquer the effects of Parkinson’s, he did something incredible in retirement—he became bigger than his sport. In his diminished state, he became a true humanitarian and citizen of the world. However flawed he was as a man—and Burns’ film shows us those flaws without reservation—he became something far greater than what he was at his physical best and at his most prolific as a speaker. If you wanted to know where your moral compass should point, he became the man to look to.

Burns’ series closes shortly after showing Ali light the flame at the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics. A series of incredible interview subjects recount their feelings on that night, and nearly to a man, they all cry. As I recalled that night myself, which I watched live on television, I broke just like those men on camera.

As Ali accepts the torch from Janet Evans, I was reminded of why I was so moved by that moment. Some who witnessed the event might say that they wept because they didn’t like seeing him that way—shaken with infirmity. But that’s not why I wept. I wept because I saw courage. By that time in his life, Ali didn’t need anything from anyone. His fourth wife, Lonnie, had made him financially stable, and there was no reason to leave the house if he didn’t want to. But Ali did want to. He wanted to be among us. To, as Bob Dylan described, “spread gladness.”

And so he did.

The episode closes with a man reading a poem he had written for Ali. It tingles the spine and tugs at the heart as the screen fades to black.

_____

What Ken Burns has accomplished with Muhammad Ali is nothing short of masterful. He took a subject that we all thought we knew through and through, and made it exhilarating. He unveiled a detailed and balanced perspective that has resulted in the greatest of all the projects that have covered this most full of American lives.

Some stories never get old, like The Odyssey, King Lear, or the true-life tale of a poor black boy from Louisville, who through sheer force of skill and will became the greatest athlete in history, and, quite possibly, the most important person of his time.

So why did we need another Muhammad Ali documentary?

Because we just can’t get enough.