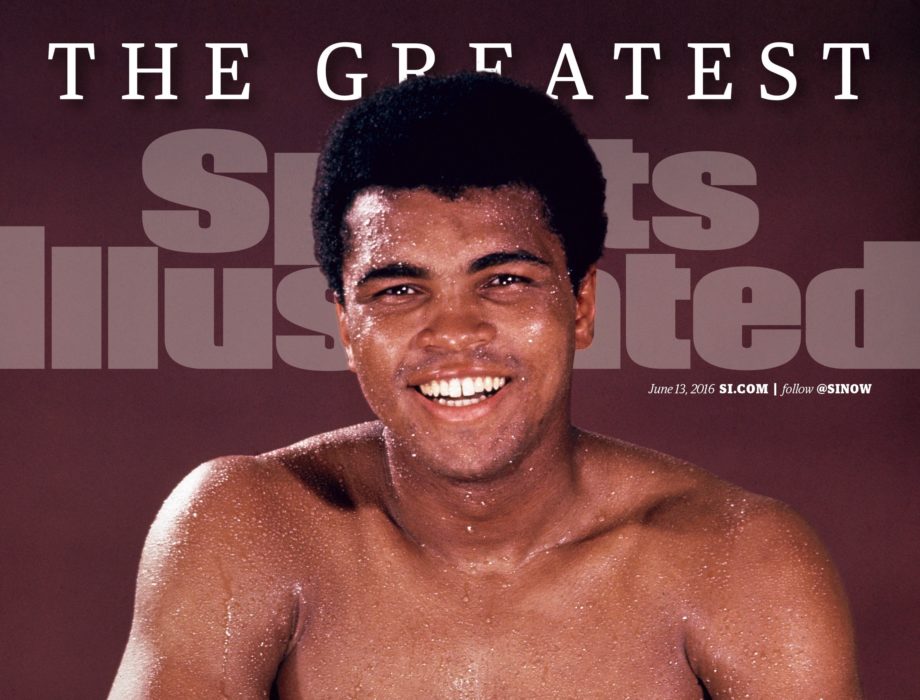

There will never be another like him.

Really, truly, it is so, it is not the time for lazy and overstated summations. Muhammad Ali died today, and there could never be another bright star of a soul like he in the realm of sports.

Floated like a butterfly, stung like a bee, did Ali, born Cassius Clay on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky; he put forth poetry in the squared circle, and from his motor mouth, and was a true original, for the way he combined athletic prowess and majestic charisma and social consciousness.

Ali was 74 years old on the day his body stopped working in a Phoenix area hospital.

The greatest boxer who ever and will ever live, if one factors in resonance of impact to the masses along with skill and will, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in the 80s, with the prevailing theory being that the ravaging disease was brought on by the punishment he absorbed in the ring.

Ali boasted and bragged from the get go, as he burst onto radars with his brash declarations of superiority, in his title win over Sonny Liston, and then in subsequent clashes with titans Joe Frazier, and George Foreman. But while he knew how to gain attention, much of it negative, from stolid sorts not comprehending that his tongue was often firmly planted in cheek, he later in life mellowed his manic act.

Ali surprised detractors by taking a stand on principle against the Vietnam war in 1967, and carved out support from critics who had to admit his anti war protest came from the heart. His ring career ceased for a spell, during his athletic peak, because he refused induction into the armed service and so gradually, his army of haters lessened. To be sure, his public worship of the Muslim faith kept him from becoming an icon to all, but as decades passed, after he hung up the gloves in 1981, with a 56-5 record, his true worth as the most compelling sports entertainer of any and all eras became set more in stone.

And know this: if a large portion of the populace was sometimes shocked and appalled by his bragging, legions of people lived through him. This man wasn’t going to take it sitting down that his skin color barred him from a whites only lunch counter, and he had the musculature of body and mouth to communicate this stance. Ali spoke to and for masses who didn’t have enough people speaking up for them. His leadership quality in this area might be his most laudable victory.

No being was better known planet wide in the 1970s; title fights dotted the world map, and every continent sported Ali rooters. A gold medal at the 1960 Olympics hinted at the trajectory of the “Louisville Lip” but only barely. Beating the glowering behemoth Liston as a 22 year old gave him license to audition the tag of “The Greatest” and by the time he won the title of heavyweight champion for the third time, in 1978, only reflexive quibblers repudiated that designation.

His skill set was not replicable. His jab was a table setter, a sharp and nasty one. His right was a chopping cross or a hook, he liked to come from the side and underneath, the better to be out of sight from most people’s peripheral vision. The left hook, he’d pile it on, clang three off your eardrum. And then he’d slide away, an Astaire in short pants, a master of a violent dance, ever unflappable but then ready to telegraph fury with a face fashioned into a snarl of viciousness.

A bike stolen by someone who deserves our eternal thanks set Clay in his path to sports sainthood. A local cop in Louisville pointed a furious 12 year old to the boxing gym to sort out his ire at the bike theft and a star was born out of the event. “I must be the greatest!” he exulted in 1964 in Miami after beating Liston, and he proved his point when he said “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcongs” when sparring with the powers that be who wanted him to enter the Army.

A loss to Frazier in the “Fight of the Century” in 1971 opened doors to people who came around to his show of humility upon tasting his first pro defeat. By now, boxing was on a sharp ascent. Into the 70s, casuals got a dose of the sport via Ali’s charming and self aggrandizing antics, often times served up by foil Howard Cosell, who stood toe to toe with Ali in the ego department.

Ali’s kryptonite was Ken Norton, but he buffed up his resume and standing from those who were seeking to pronounce him over and done with wins over Frazier, in January 1974, and George Foreman, in “the Rumble in the Jungle.” That October 1974 classic re-proved that his boasting was backed by high gloss talent and guts galore. More proof came in the 1975 “Thrilla in Manila,” where he bested eterna rival Frazier. He played out the spring with some sluggish outings, and mustered a last ring hurrah by taking down young Leon Spinks after the kid took his crown. Along the way, he masterfully played the press like a maestro of the violin, talking and teasing retirement, then roaring to action to attempt to price himself immune to aging’s body work on the ropes.

As a family man, Ali admitted his imperfection but his spiritual base has his children lauding his efforts to be daddy while wearing that cape and crown. Ali married four times and the fourth to Lonnie, proved durable. Seven daughters and two sons carry the DNA of this one and only. Business manager Gene Kilroy lives in Vegas, and always shares stories of Ali’s decency as a family man.

This day one figured might come earlier but you wanted it postponed forever. He was pre deceased by his sidekick and tutor Angelo Dundee, in 2012, and Frazier the year before and Norton in 2013, and though in recent years his ability to speak disappeared, we were reminded by his aggressive declaration that he never regretted his time spent in the ring. He knew the risk and wasn’t going to second guess a higher power. To many of us, he served as a higher power, one suited to reality-based people. He admitted foibles, and in the second half of his laugh devoted himself to messaging of love and acceptance. That wouldn’t be enough to unbelievers who couldn’t forgive anti white supremacist slams from him during his Nation of Islam period, and calls to keep races seperate in romantic setups.

We wonder—would this world be able to handle his lip in a more (selectively) politically correct age? I don’t think Archie Bunker gets on the air today and I think Ali would explode minds. But boys all the way to men would still be doing that signature step, the Ali Shuffle, which out stripped Michael Jackson’s Moonwalk in popularity.

The world of boxing has undeniably shrunk, sad to say. Even if you expected this end for some time, the impact of the death of Muhammad Ali hits hard. His feats live on, on screens and pages and memories, but that the gold standard for fighting, in and out of a ring, has departed, it leaves a hole that can never be filled. The context of the age, with the civil rights battle being so actively fought, asked much of citizens and this one reacted with a majesty unparalleled. Poetry in motion, in action inside and out of the ring. He delighted and dismayed, tested and shredded and then was bested by boundaries and limits of skill and finally, time. It minimizes his legacy not at all. Muhammad Ali was and is, and always will be, The Greatest.

Rest in peace, champ, thank you kindly for being so generous with your talent and spirit.

Woods email is Fightwrite@gmail.com. Twitter is Woodsy1069.