-

Boxing

BoxingLadies Night In London: Price and Dubois Get Big Victories

In a historic all-women’s world championship boxing event on Friday at the iconic Royal Albert Hall in London, fans were treated to outstanding action, including an all-British...

-

Boxing

BoxingCanelo Álvarez Expects A Difficult Fight Against William Scull

Unified super middleweight champion Saul “Canelo” Álvarez of Guadalajara, Mexico (62-2-2, 39 KOs) seeks to make history when he takes on IBF titleholder William Scull of...

-

Boxing

BoxingJose Valenzuela Determined To Remain Champion On Saturday: ‘I’m Here To Stay’

WBA junior welterweight champion Jose Valenzuela of Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico (14-2, 9 KOs) envisions a certain outcome in his first title defense against Gary Antuanne...

-

Boxing

BoxingNew York Welcomes Tank Davis and Lamont Roach at Gleason’s Gym

Reigning WBA Lightweight World Champion Gervonta “Tank” Davis and WBA Super Featherweight World Champion Lamont Roach kicked off fight week events on Wednesday with a media...

-

Announcements

AnnouncementsLamont Roach Jr. Ready for Battle with Gervonta Davis Saturday in Brooklyn

WBA Super Featherweight World Champion Lamont Roach Jr. of Washington DC (25-1-1, 10 KOs) gets the opportunity of a lifetime on Saturday as he battles undefeated...

-

News

NewsRevenge Sweet for Dmitriy Bivol In Beterbiev Rematch

Dmitriy Bivol of Indio, California (24-1, 11 KOs) is now the unified, undisputed world light heavyweight champion. Bivol delivered a scintillating performance in another close fight...

-

Boxing

BoxingJoseph Parker Blasts Out Martin Bakole

The co-main event ended in dramatic fashion, as WBO interim champion Joseph Parker of New Zealand (36-3, 24 KOs) drilled replacement opponent Martin Bakole of the...

-

News

NewsVergil Ortiz Jr. Outclasses Israil Madrimov

Giant killer Agit Kabayel survives a knockdown to stop Zhilei Zhang in six rounds.

-

News

NewsBeterbiev vs Bivol 2: Weigh-In Photos & Predictions

All but one fighter on the Beterbiev vs Bivol 2 card Saturday in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, have made weight and are ready to shine on a...

-

News

NewsShakur Stevenson Carrying The ‘Same Mentality’ Against Josh Padley

Despite a change of opponent, WBC lightweight champion Shakur Stevenson’s objective will remain the same when he takes on Josh Padley on Saturday at the ANB...

-

News

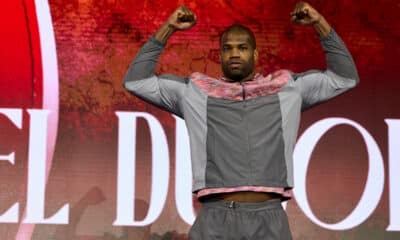

NewsDaniel Dubois Ready To ‘Steal The Show’ Against Joseph Parker On Saturday

IBF heavyweight champion Daniel Dubois of London, England (22-2, 21 KOs) seeks to take the spotlight when he makes his second title defense against Joseph Parker...

-

News

NewsBeterbiev vs Bivol 2 Kicks Off With Grand Arrivals Tuesday

In anticipation of a boxing card loaded with talent and meaningful fights, unified light heavyweight world champion Artur Beterbiev of Montreal (21-0, 20 KOs) and former...

-

News

NewsDuarte Stops Madueño, Aims For Title Fight

Oscar Duarte and Miguel Madueño delivered a love letter for boxing fans who love some Mexican style action in Anaheim Saturday on Valentine’s Day weekend. Duarte...

-

News

NewsBarboza Jr. Beats Catterall on Enemy Turf – Teofimo Next?

Tense moments ticked by for Jack Catterall of England and Arnold Barboza Jr. of El Monte, California, as they waited to hear the scorecards in what...

-

News

NewsBoxing Lovers Valentine Weekend Schedule and Preview

Admit it, guys. You’ve tried to weasel out of a date night on a special occasion, including Valentine’s Day, because there was a killer boxing card...

-

New York

New YorkNo Love Lost Between Keyshawn Davis and Denys Berinchyk

Based on the final pre-fight news conference in New York Wednesday, Keyshawn Davis and Denis Berinchyk won’t be exchanging Valentines before their title fight on Friday,...

-

News

NewsCanelo Álvarez and Boxing’s Future, Explained

Now that the dust has settled, what does the Canelo Álvarez deal with Riyadh Season mean to the sport of boxing, and its fans long term?