-

Worldwide4 hours ago

Worldwide4 hours agoCanelo vs Crawford: Official Weigh-In Results

Like watching jockeys saddle up in the paddock and take the post parade to the track, the boxing weigh-in provides the final clues about the outcomes...

-

Boxing5 hours ago

Boxing5 hours agoLewis Crocker vs Paddy Donovan 2: The Dramatic Story So Far

Lewis Crocker of Belfast, Northern Ireland (21-0, 11 KOs) will take on Paddy Donovan of Limerick, Ireland (14-1, 11 KOs) on Saturday when the pair compete...

-

MMA10 hours ago

MMA10 hours agoNoche UFC Features 5 Mexican Fighters as Brazilian Featherweights Headline Texas Event

Diego Lopes (26-7) and Jean Silva (16-2) will come together in an all-Brazilian affair on Saturday night when they headline Noche UFC in San Antonio, Texas....

-

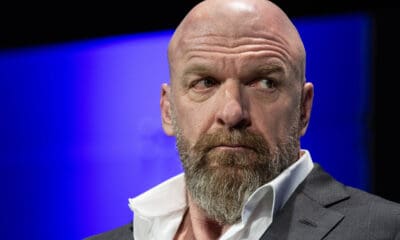

Pro Wrestling11 hours ago

Pro Wrestling11 hours agoAAA Give Significant Control Of Company To WWE And Triple H Following Takeover

WWE, as part of TKO Group Holdings, announced its acquisition of the leading Mexican Lucha Libre promotion, AAA, back in April 2025, in partnership with Mexico-based...

-

Boxing18 hours ago

Boxing18 hours agoCanelo vs Crawford: The Prediction Dynamic

Terence Crawford’s challenge against Canelo Álvarez is of this same mold as the audacious challenge by then undisputed light heavyweight champion Roy Jones Jr. against WBC...

-

Boxing22 hours ago

Boxing22 hours agoSerhii Bohachuk Seeks Revenge in Brandon Adams Rematch

Super welterweight Serhii Bohachuk of Ukraine (26-2, 24 KOs) has just two losses on his record. One came in a razor-thin majority decision against Vergil Ortiz...

-

MMA23 hours ago

MMA23 hours agoUFC Noche Fighter Payouts: How Much Will the Headliners Earn?

September didn’t feature a numbered pay-per-view, but the UFC is still set to deliver with three action-packed Fight Night cards. The month kicked off in Paris...

-

Pro Wrestling1 day ago

Pro Wrestling1 day agoWrestleMania 43 Reportedly Taking Place In Saudi Arabia

The Road to WrestleMania will begin next year, starting with the Royal Rumble event. WrestleMania has been a staple of WWE PLEs since its inception in...

-

Boxing2 days ago

Boxing2 days agoBet on Mbilli vs Martinez Stealing The Show in Las Vegas

Super middleweight Christian Mbilli might STILL be the best fighter you don’t know about. But you need to get acquainted with him, whether you speak French...

-

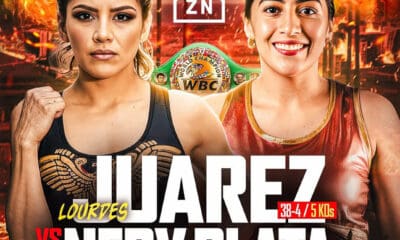

Announcements2 days ago

Announcements2 days agoMVP Prospects 16 Features Juarez vs Plata Title Fight on Oct. 18

Most Valuable Promotions (MVP) announced the company’s return to Texas for Most Valuable Prospects 16, an MVP Championship Double Header on Saturday, October 18, at the...

-

Boxing2 days ago

Boxing2 days agoCanelo, Crawford, and Boxing History: When Titans Collide

On a mid-September night in Las Vegas at Allegiant Stadium, boxing history will be made as two of the sport’s modern titans collide: Canelo Álvarez and...

-

AEW3 days ago

AEW3 days agoWWE Set To ‘Counter-Program’ AEW All Out PPV With Return Of Popular Superstar

WWE is set to counter-program AEW’s All Out PPV on September 20th with ‘WrestlePalooza,’ according to recent reports, with a former Superstar set to make her...

-

Boxing3 days ago

Boxing3 days agoBig Prize For Winner of Parker vs Wardley: Oleksandr Usyk

The heavyweight showdown between Joseph Parker and Fabio Wardley at The O2 Arena in London on Saturday, October 25 offers more than a victory. A shot...

-

Boxing3 days ago

Boxing3 days agoTerence Crawford’s Super Middleweight Sparring Partner Previews Canelo Super Fight

Terence Crawford of Omaha (41-0, 31 KOs) will compete in one of the biggest fights of his life on Saturday night when he takes on fellow...

-

Pro Wrestling3 days ago

Pro Wrestling3 days agoAJ Lee’s First Match In 10 Years Officially Announced On WWE Raw

AJ Lee took the wrestling world by storm after her return on Friday Night Smackdown last week. On the latest episode of Raw, Lee appeared and...

-

MMA4 days ago

MMA4 days agoRonda Rousey Delivers Defiant Update on UFC White House Return Speculation

Back in 2011, Dana White famously declared that women would never compete in the UFC. Yet just two years later, the promotion crowned its first women’s...

-

Amateur4 days ago

Amateur4 days agoTeam USA Boxers Advance Monday at World Championships

Day 5 of the 2025 World Boxing Championships saw two more victories from Team USA Boxing in Liverpool. Featherweight (54-kilogram) Yoseline Perez of Houston, and heavyweight...

-

Boxing4 days ago

Boxing4 days agoCanelo vs Crawford Fight Week Schedule in Las Vegas

No one celebrates Mexican Independence Day like undisputed super middleweight champion and the face of boxing, Saul “Canelo” Álvarez. This year’s festivities may be his biggest...

-

Pro Wrestling4 days ago

Pro Wrestling4 days agoAJ Lee’s Return Was A “Curtain Sellout” Backstage

AJ Lee’s return finally happened after over a decade. She’s currently feuding with Seth Rollins and Becky Lynch after the latter attacked CM Punk. This wasn’t...

-

AEW4 days ago

AEW4 days agoChristian Cage Says He’s Having The “Greatest” Run Of His Career In AEW

Wrestling is one of those sports where age really doesn’t matter. You can be the best 20-year-old wrestler in the world, but that doesn’t mean you’ll...