Anniversaries and birthdays. They’re the bookmarks of life. They are used to commemorate and remember important events. Happy ones. Sad ones. Patriotic ones. Memorable ones. Exciting ones. Unforgettable ones.

This is a story of one of those anniversaries. One of those special, memorable, exciting and unforgettable anniversaries.

This week is the 40th anniversary of making what was called the “Sugar Ray Leonard 7-UP commercial.” Those who are old enough will probably remember the commercial. For the ones who don’t know about it, the commercial is below for you to watch—and enjoy. It’s one on the most smile-inducing commercials ever made.

There’s a reason I remember it so well.

I was in it!

How’d that happen? Here’s the story:

It was the week after Easter. It was also the week after the boxing quadruple-header from three separate sites, with all the fights being shown on ABC-TV. In Las Vegas was the Larry Holmes v Leroy Jones heavyweight title fight. (Note: Yes, you hear it right. Howard Cosell refers to Jones as “a big, fat blubbery guy” in the lead-up.)

In Knoxville, Tennessee, boxing fans were given a double-header, with the Marvin Johnson v Eddie Gregory WBA light heavyweight title fight and the WBA heavyweight title fight between titleholder John Tate and Mike Weaver. (I was ringside for this card as editor of Ring Magazine, wanting to cover my longtime friend, Eddie Gregory, as he went after his first world title).

The third fight shown on ABC took place in Landover, Maryland. This card featured Sugar Ray Leonard, who had won the title from Wilfred Benitez four months earlier. Leonard was making his first defense, facing Britain’s hard-hitting Dave “Boy” Green. Holmes, Weaver, Gregory and Leonard all won with dramatic and impressive knockouts.

After his title-winning victory, Gregory pulled me aside when he came out of the ring and said, “Come to my dressing room. I have something to tell you.” I couldn’t imagine what it was. I found out a few minutes later.

“My name is no longer Eddie Gregory,” he told me.

“It’s not?” I asked him with absolute puzzlement in my voice.

“It’s not,” he replied. “I am now Eddie Mustafa Muhammad.”

I stared at my friend for a moment, then said, “It’s taken you 28-years to make a name for yourself, and now you’ve gone and changed it!” We both laughed.

“Well, this is real, very real he said. “I am a Muslim and I now am Eddie Mustafa Muhammad.”

“You’ve also got another new names,” I said.

“What name is that?” he asked.

“Champ,” I told him. “You have a new name and a new title.”

He put an arm around my shoulder and said, “Let me go out there and address the media.”

I smiled at him and said, “After you, Champ.”

***

A few days after the I returned home from Knoxville, I answered the phone at Ring Magazine. It was a man from an ad agency with a question. I introduced myself as the Editor of Ring Magazine.

“We’re looking for a boxer to be in a commercial,” said the man at the other end. My eyes opened wide when his next sentence came out.

“It’s a 7-UP commercial starring Sugar Ray Leonard.”

“Tell me more,” I said excitedly.

“Well, we’re looking for an ex-boxer or at least somebody who has a solid background in boxing,” said the man. “We’d prefer he be an ex-boxer, between 5’6″ and 5’8″, in his late 20’s to early 30’s , between 140 and 147 pounds and he’s also gotta be white.”

There was silence for a second or two as my mind raced. Then I said, “Okay, let’s see. He’s gotta be an ex-boxer, between 5’6″ and 5’8″, in his late 20’s to early 30’s, between 140 and 147 pounds and he’s gotta’ be white. I’ve got just the guy for you.”

“Who?” asked the man. “Do you have his number? Who is he?”

“You’re talking to him,” I said.

“Wait a minute. I thought I was talking to the Editor of Ring.”

“You are.” I told him. “But I’m also an ex-boxer who fits every one of your qualifications. I’m also in terrific shape. Hire me.”

“Fine,” said the desperate ad-man. “Just show up at 6:00 a.m. tomorrow morning at my office. You’ll fill out a couple of papers and a bus will take you and the other actors over to the site.”

The ad-man gave me the address to his office, which was a few blocks uptown from my office at The Ring. He thanked me for helping him out. I thanked him for giving me the opportunity. As I hung up, I heard Bert Sugar, in his unmistakable, rich baritone voice, stepping off the elevator.

“I walk in and the landlord says he is turning off the water in the bathroom today to do some plumbing work, so we’ve got no bathroom. Then I get on the elevator and the damn thing is the slowest elevator in the world!” he complained to nobody. “What else is going to annoy me today?”

“Oh, wonderful,” I thought. “Bert’s in a pissed off mood and I have to tell him I’m taking off the day tomorrow when we are on deadline. Oh well, he’ll just have to deal with it!”

To my surprise, Bert wasn’t angry to hear I would be taking the following day off to take part in a commercial. If anything, he was happy that I’d be spending the day with Sugar Ray Leonard.

“You’d better come back with a story,” Bert said. Then he picked up a pile of completed stories from his desk, all written for the next issue and added. “Take these stories and go edit them. I need them by lunch-time.”

I bolted out of his office, through the adjoining reception area and into my private office, where I got right to work on editing the stories Sugar handed to me, then writing up my coverage of the Weaver-Tate and Gregory, er, Muhammad-Johnson fights.

The following morning, I took a 5:00 a.m. Long Island Railroad into New York City. The ride takes 55 minutes, and I—along with the other actors—had to be at the ad agency’s office a few blocks away Penn Station by 6:30. When I arrived at the agency a few minutes after 6:00, an agency representative had me sign a contract, then put me—along with a dozen other actors, on a bus, headed to the site of the filming.

The commercial was filmed in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I thought it kind of strange to be filming a commercial in Williamsburg, which is a turn-of-the-century town, largely inhabited by Hasidic Jews. Just a few blocks away from the “shoot” was Rutledge Street, where Grandma and Grandpa Gordon raised my father, Carl, and his sister, Lila. It is also where I spent many of my childhood weekends.

The bus arrived at the gym at 6:30. On the bus with me were 20 actors. As we walked into the gym, a lady with a clipboard asked each actor his name, then checked it off on a list she had. I gave her my name, then proceeded forward. As I took a step, I walked into an outstretched arm. A large outstretched arm. It belonged to Leonard’s longtime friend, physical conditioner, bodyguard and aide-de-camp, Janks Morton. Morton was a mountain of a man, all 6’2″, 230 pounds of him. He had boxed as an amateur, winning all 20 of his bouts by knockout. As a softball player, he was a little bit better. He didn’t just hit balls—he put them into orbit!

“Hold up!” Morton commanded me. “No reporters are allowed in here!”

I looked at him and smiled.

“I’m not here as a reporter, Janks,” I said sheepishly. “I’m here as an actor. Where’s Ray?” I thought I had him.

“He’s in this room changing,” said Morton, pointing to the dressing room door.

As I started forward to see Leonard, Janks stopped me again.

“You’re an actor, right?”

I nodded.

“Then go upstairs with all the other actors. Go up there and hang out with them. Just do the business you’re here for today and keep away from Ray!”

As I was about to head upstairs, Leonard’s voice shot from behind the dressing room door. He had overheard our conversation.

“It’s okay, Janks. Randy’s okay. Come on in, Randy. ” I looked at Janks, smiled, nodded at him and walked into the dressing room. There was Leonard, wearing a red sweatsuit. Standing next to him was his five-year-old son, Ray Jr. Papa Leonard and I embraced.

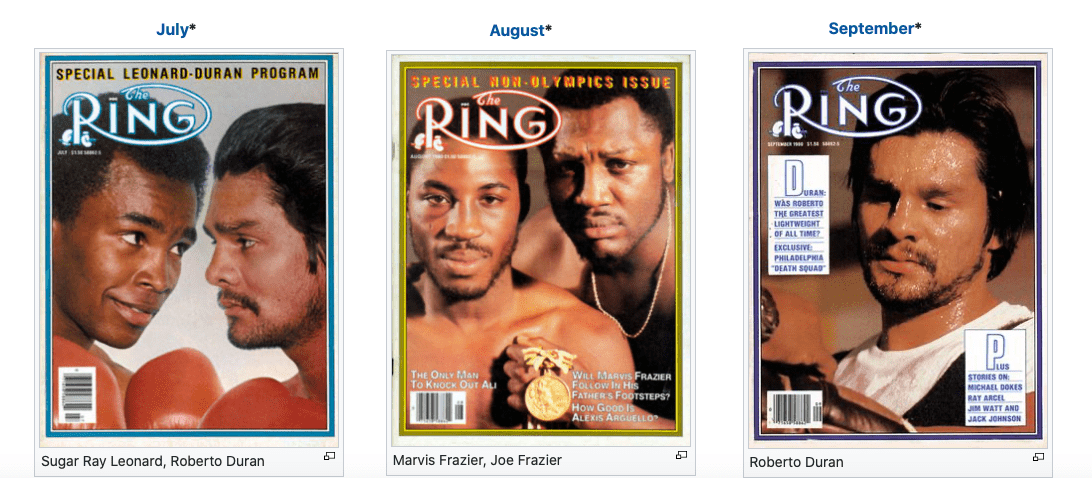

Before I could get any words out, Leonard said, “I’m glad you’re here. I don’t know if you heard, but I’m gonna be fighting Roberto Duran in June. What do you think of the fight?”

What do I think of the fight? Hmm. Why would he be asking me that question? Through the remainder of the day, I found out why. For the first time in his career, Leonard was not totally sure of himself. He had questions about his ability, his toughness, his speed, his stamina and his chin.

“Do you think he can hurt me?” “Can I take him out?” “How would you rate his power as a welterweight?” “Did he hurt Carlos Palomino?” “Do you think I’m that much faster than him?”

Those were some of the questions Leonard threw at me during almost every lengthy break we took. His confidence, normally sky high, was missing.

During one shooting session early in the morning, it became obvious that some of the background extras, who were supposed to be moving around the floor looking like boxers working out, knew nothing about boxing or how a fighter moves. Some of the effeminate moves we witnessed were actually rather hysterical. Panicked, the producer put his hands to his head and moaned.

“What am I gonna do? I need a room full of boxers and I’m sent a group of pansies! What am I gonna do?”

Leonard and I looked at each other quizzically.

“Let’s go!” we said in unison. We stood up, called the actors together, put them in line and proceeded to give them a crash course in boxing. We showed them how to stand, how to hold their hands and how to move. Ten minutes later, we had a room full of “fighters.” It was one of the few times all day that Leonard didn’t ask me something about Duran.

At lunch, Big Janks came over to me and said, “Listen, you and Bert are selling pictures of Ray over at Ring. We want a percentage!”

“But, Janks, we’re selling pictures of every fighter,” I tried to explain.

“Ray ain’t every fighter,” said Janks. “Tell ya’ what. We’ll make you a good deal. We get 60%, you get 40%.” Leonard would have cringed had he heard Janks trying to shake me down. But I stopped Big Janks in his tracks when I told him, “Okay, you got a deal. Let’s see now. We sell about 10 photos a month of Leonard. At three dollars a photo, that’s 30 dollars. Your cut will be 60%. That means you’ll be getting something like 18 dollars a month.” Then I added,” Some months are slower than others. Sometimes we don’t sell more than five or six photos.”

Janks looked at me in shock.

“What! You’ve got to be kidding! Put the money in your pocket!” We both laughed. From that moment, Big Janks and I have been friends.

For the commercial, Leonard was paid about one million dollars. Although I had a principal role, being seen right next to Ray and Ray Jr., I was paid a whopping $250. The reason: I was not in AFTRA or SAG, which pays its members residuals. It was worth it, though. It was a day getting to know Leonard even better than I already knew him and becoming friends with both he and Big Janks, friendships which have lasted to this very day.

When I got on the bus heading back to the city, I stared out the window as we pulled away from the gym and “The El” — the rickety old elevated train tracks–next to it. I thought about the day and how much fun it had been. I thought of all the questions that Leonard had asked me. I thought of them over and over. His questions had led me to believe one thing.

He was not going to beat Roberto Duran in Montreal.

Editor’s Note: In the video’s opening, you see Ray Sr. and Jr. hitting the speed bag. Leaning in is the “trainer.” In the orange shirt, black trunks and white shoes is Randy Gordon, coming towards the camera shadow boxing, then heading to his right. He’s also in the shot nine seconds later, as big Ray and little Ray are sitting on the ring. Randy can be seen shadow boxing across the ring.