It was a February night 40 years ago that Rudy Hernandez scored the biggest win of his boxing career, upsetting undefeated Lupe Aquino. The hard-punching Aquino would go on to win a world title four years later. But on this night, it was Hernandez who was saluted with cheers and whistles from the Mexican and Mexican-American crowd at The Forum in Inglewood.

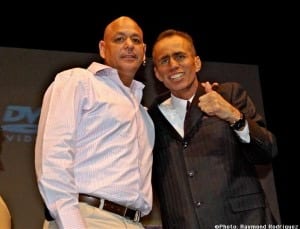

By 1988, Hernandez had a 14-2-1 (6 knockouts) record. But he was presented with a proposition that appealed to him more than fighting. His little brother – a promising professional named Genaro – convinced Rudy to retire and become his full-time trainer. It turned out to be destiny for the Hernandez brothers as Genaro – with Rudy as his guiding force – became a two-time junior lightweight world champion and one of the best fighters of his era.

More than two decades later, as Genaro lay on his deathbed – his body overwhelmed by a rare, aggressive and devastating form of cancer – he pulled his big brother near him for the last time and looked at him with big green eyes.

“I said, ‘We did good, huh?’” Rudy Hernandez recalls. “He said, ‘Yeah, and we fucking did it together.’ He died feeling proud and good about what he had done. At the end of the day, working with my brother was the best decision I ever made.”

****

The 2024 class of the International Boxing Hall of Fame will be revealed on Dec. 7. Genaro “Chicanito” Hernandez has appeared on the ballot for a decade now. Rudy Hernandez doesn’t feel one way or the other about his brother’s prospects of being inducted.

To him, it’s too little, too late.

“I think it would be an honor for his kids to know their dad is in the Hall of Fame. But, for me, it doesn’t mean anything anymore because he’s not here,” Rudy said. “I would’ve liked for it to have happened when he was here.”

Still, this could be the year that Genaro finally achieves boxing immortality. There were a minimum of shoo-in selections on the 2024 ballot and many fighters, including Hernandez, have a good shot.

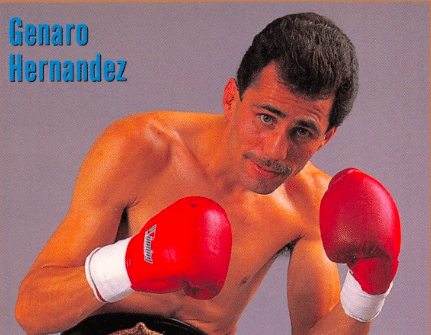

A Los Angeles native, Genaro Hernandez – nicknamed “Chicanito” (Chicano is a Civil Rights-era term for a Mexican-American) – retired in 1998 with a record of 38-2-1 (17 knockouts).

Well-learned and highly disciplined, Genaro threw every punch in the manual with precision, whether it be at long range or on the inside. He used that style to build a 23-0 record mostly on the Southern California circuit before winning the vacant WBA junior lightweight title in 1991 with a 9th-round knockout of Daniel Londas in Londas’ native France.

Genaro made nine defenses of the crown against an array of styles, outslugging and outmaneuvering everything from tall, difficult stringbeans like Raul “Jibaro” Perez to short, powerful fireplugs like Frankie “Panchito” Warren to unpredictable former world champions like Jorge “Maramero” Paez.

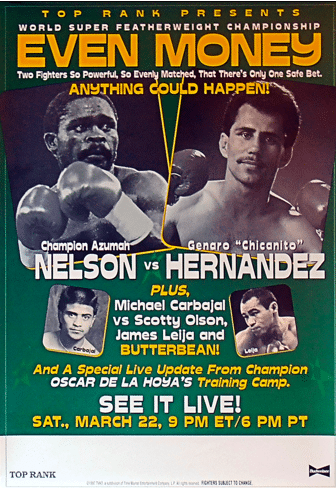

He then won the WBC junior lightweight title in 1997 with a career-best win over future Hall of Famer Azumah Nelson, a fight he could’ve won by disqualification when Nelson nailed him with a punch after the seventh-round bell. But rather than win the title via DQ, Chicanito opted to keep fighting, winning a split decision. He then made three defenses.

The only fighters to defeat Genaro were two of the best to ever do it: Oscar De La Hoya and Floyd Mayweather.

****

Initially it didn’t appear Genaro – one of six Hernandez children – had the gumption to be a fighter. Rudy – four years older – would needle him on purpose, like all big brothers do. He reveled in it. The antagonizing got worse once Genaro followed Rudy’s footsteps into the boxing ring, where he’d sit and watch him train.

“He was the grumpy little kid, all miserable all the time. I would piss him off and make him cry,” Rudy said. “He was 18 years-old and he would be in the ring sparring someone and there would be tears coming down his face.”

As Genaro got older, his natural talent began to show itself. An all-around athlete who was gifted at football, basketball and soccer, the crying was soon replaced by confidence. As Genaro moved up the ranks, going from promising contender to two-time world champion, Rudy morphed from antagonizer to protector.

Rudy was fierce about looking after his little brother.

“There were times I had to pull him away because people weren’t respecting his time,” Rudy said. “The part they do not understand is that, when you’re a world champion, there’s schedules to adhere to. You’ve got to do interviews, attend meetings. I’ve had people say, ‘fucking Rudy, you’re such an asshole.’ But I don’t work for the media. I work for the fighter. Genaro struggles his ass off to make weight and I’m supposed to accommodate the media? Get the fuck out of here.”

Over time, Rudy – who replaced his father Rodolfo as Genaro’s trainer because Genaro and his dad were so much alike they couldn’t get along – became the father figure. It was a bond built on respect, trust and love. It became stronger with every gym session, every fight and every win.

It was Rudy who was at Genaro’s side when he beat Londas, Perez and Paez. It was Rudy who gave him encouragement when the fans accused Genaro of quitting against De La Hoya. And it was Rudy who would lift Genaro up in what would be the biggest victory of his career.

****

Genaro had been fighting a textbook fight against Nelson, March 22, 1997, in Corpus Christi, Texas, firing his long jab, quick right hand and the follow-up left hook/uppercut all night long. His long frame was giving the shorter Nelson serious problems. He was in control when, at the end of the seventh round, Nelson wound up with a big left hook that connected seconds after the bell. It caught Genaro on the throat as his back was on the ropes and dropped him in a heap. Genaro had a dazed look on his face and the fight appeared over. Had he stayed down, he would’ve won by disqualification.

But Rudy said no way.

“Me being me, I said ‘Champions are made winning in the ring and not lying on their back,” Rudy said. “I said, ‘Get your ass up and continue painting this masterpiece.’”

He did and won a split decision – gaining redemption for the De La Hoya fight. It was the crowning achievement of a very good – and maybe a great – career.

“A lot of people called him a quitter when he lost to Oscar De La Hoya,” Rudy said. “I didn’t give a rat’s ass about other people’s opinions. But that decision (to keep fighting against Nelson) sealed my brother’s future in the sense that he did the honorable thing.”

****

After retiring in 1998, Genaro enjoyed life. Always with a smile, he served as a boxing analyst for Top Rank and was ringside for many big fights. His good looks and his sunny personality made him a natural behind the microphone. He enjoyed being with his wife and two children.

But in 2008, he was diagnosed with stage four rahabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that typically afflicts children. About 60 percent of all people who are diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma are under the age of seven. Only 400 or so cases are diagnosed in the United States each year, according to Yale Medicine.

Genaro had no symptoms, he told myboxingfans.com in 2008. Just a small lump near the jaw area that he thought was fatty tissue. After it was removed, he noticed two more lumps near his collarbone. The tests came back negative but, after a biopsy, tumors were found growing in his sinus and lymph node.

It seemed unfathomable. He had been a world-class athlete who lived a clean life. He didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink. He lived clean. How could this be?

“We were in the car, I was driving, and we had our family with us,” Rudy said. “He started crying, telling me had had stage four cancer. I remember saying, ‘Shut the fuck up. I only have one question for you: did he give you an expiration date?’ He said, ‘What?’ And he’s not sobbing anymore. I said, ‘I’m asking you did they give you an expiration date? Did they give you two months? Six months to live?’ He said, ‘They didn’t tell me that.’ I said: ‘Then I don’t want to hear you crying and bitching. I want you to take a step back and say: ‘How are we gonna beat this?’”

Genaro took to the task. He endured the chemotherapy sessions and dropped in weight but maintained his positive outlook. He had good days and bad days but had survived three years. He was fighting the good fight. But then he suddenly took a turn for the worse. And when the end came, it came swiftly.

Genaro “Chicanito” Hernandez died on June 7, 2011. He was 45 years old.

Rudy said four people went out of their way to help Genaro in his time of need: Hall of Famer and former sparring partner Shane Mosley; legendary promoter Bob Arum of Top Rank Boxing; Teiken Promotions’ Akihiko Honda; and boxing superstar Mayweather.

“Shane loved my brother and cared for him,” Rudy said. “Bob Arum and crew, they helped my brother the last three years of his life. They took care of all the medical expenses and didn’t want anyone to know. But I have a big mouth. People are all good to talk shit about them but there’s another side to them. Mr. Honda from Teiken Promotions would wire money into my brother’s account. And also the undefeated 50-0 Floyd Mayweather, he reached out to my brother. Genaro showed me the text Floyd sent him. He always referred to my brother as ‘Mr. Hernandez.’ It said, ‘Look Mr. Hernandez, here is my phone number. If there is anything you need, please reach out to me. Just please don’t give my phone number to anybody.’ He paid my brother’s funeral expenses – over 10K.”

Arum, who said he believes Hernandez belongs in the Hall of Fame, said: “Genaro was a terrific young man and a great warrior. But more than that, he was always a gentleman. I was devastated when I learned of his disease. I just wanted to make sure that he received the best possible medical attention.”

Mayweather told the U.K. Sun in 2020 that Genaro was his hero during his teenage years.

“When I was 16, I had a poster, right above my head, Genaro ‘Chicanito’ Hernandez,” he said. “And I used to watch him on TV fight and I said nobody will beat that guy.”

****

Twelve years after his brother’s untimely death, Rudy still doesn’t understand it.

“He still had a 10-year-old to take care of and was full of life. He wanted to live,” said Rudy, now 61. “I’m not a completely ungrateful person. But since that day he passed away, I no longer have a relationship with God. We are no longer on talking terms.”

Rudy’s church is, has been, and always will be, the boxing gym.

“The boxing gym is God’s second home, why? Because they’re all here in harmony,” he said. “Yes, they’re beating the shit out of each other. But they’re all happy inside the gym. Everything is better there. Once you leave the gym, that’s when reality kicks in. I hate it out there. I wish I could stay inside the gym all the time. I see boxing as a savior.”

Starting with his days working with his brother, Rudy has grown into one of boxing’s premier trainers and cornermen. He emphasizes old-school techniques and practices. He prefers shadow-boxing to showy exercises of mitt work; and he emphasizes sparring and hard work. His prized pupil these days is WBC super flyweight champion Jyunjin “Junto” Nakatani, 26-0 (19 knockouts), of Japan.

He also trains Anthony “La Princesa” Olascuega, 6-1 (4 KO’s), a 24-year-old bantamweight who has lived with Hernandez for several years. He is one of several youth that Rudy has taken in, getting them off the streets and helping them find their paths.

“La Princesa came to live with me when he was 14. He’s been with me ever since. He has no plans of leaving,” Rudy said. “Maybe that’s why I was put on this earth – to help people.”

Rudy’s compassion is much like his Genaro’s, who was universally admired.

Admired mostly by his guiding force – his trainer, his protecter, his brother.

“He went to sleep on a Sunday, close to 7 p.m.,” Rudy said. “I remember there were a lot of people there. I was the last one to speak with him. I remember apologizing for not being able to save him. I’m the older brother. I would’ve traded places with him in a heartbeat.”

Matthew Aguilar may be reached at maguilarnew@yahoo.com @MatthewAguilar5 on Twitter