A little over a decade ago former journeyman heavyweight David Jaco, now 66, was holding court at the Oasis Bar in Sarasota, Florida, one town over from Bradenton, where he has resided for over 30 years. Even though he is 6’6” tall and weighs about 250 pounds, from a distance he looks more like a gangly, loose-limbed retired basketball player than a former boxer.

Still ruggedly handsome, as well as being a world-class raconteur, Jaco was drawing a crowd, as he often does.

That didn’t sit well with a short, drunk, muscular fellow who was upset at all of the attention Jaco was garnering. As the brooding man sat drinking alone, Jaco was surrounded by friends, some of whom he had met just minutes before, and all of whom were reveling in the free-spirited Jaco’s stories of a life well lived.

“Hey big guy, I bet I can kick your bleeping ass,” the man screamed at Jaco. As all heads turned toward the aggressor, Jaco looked into the man’s eyes.

His German, Swiss, American Indian and English visage was smiling as Jaco politely asked what the hubbub was about. The man mumbled some more expletives and squared off. He had no idea what he could have been in for.

“I said ‘you’re probably right,'” Jaco laughingly recounted. “Of everyone in this bar, you’re probably the only guy that can whip my ass. But please don’t.”

The protagonist lost his steam and quickly retreated. Jaco went back to doing what he does best, which is having a good time and making new friends.

“It takes a better man to walk away from bullshit,” he explained. “It wouldn’t have done me or anyone else any good to put that guy in his place.”

One can only wonder if that man ever realized how lucky he was that Jaco is so mild-mannered and good-natured.

Between 1981 and 1994, Jaco traversed the globe, fighting such championship caliber opponents as Mike Tyson, George Foreman, Buster Douglas, Tony Tucker, Oliver McCall, Tommy “The Duke” Morrison, Mike Weaver, Alex Stewart, Alexander Zolkin, Bert Cooper, David Bey, Jose Ribalta, Elijah Tillery, and Adilson Rodriguez.

In compiling a deceptive record of 24-25-1 (19 KOS), he laced up the gloves throughout the United States, as well as in China, Brazil, Denmark, Germany, South Africa, and Cameroon.

His biggest win was a seventh round TKO over previously unbeaten Donovan “Razor” Ruddock in April 1985.

Jaco did not even start boxing until the age of 24, when he, and hundreds of others, were laid off from Interlaken Steel in his hometown of Toledo, Ohio. Like so many of his friends, he began working there straight out of high school and assumed he’d be employed there for the next 40 years. After being let go, Jaco, who by then had a wife and twin sons, Aaron and Adam, found himself in dire straits.

At the time the Toughman craze was sweeping the nation and Jaco, who was a natural athlete with a great right hand, was lured by the opportunity for quick money. Before long he developed such a fearsome reputation on the Midwest circuit that no one would fight him.

His Toughman promoter, Art Dore, turned him pro in 1991, and Jaco won his first 12 fights, 10 by knockout. In his next bout Dore foolishly matched him with Carl “The Truth” Williams, a sensational amateur who was 10-0 as a pro. The much more experienced Williams stopped Jaco in the first round.

“Williams was in the prime of his life,” said Jaco. “I was still learning. I shouldn’t have been fighting him, but didn’t know any better. He caught me in the body, and then an uppercut flattened me out. When the fight was stopped between rounds, I remember thinking, ‘What kind of shit is that? If you’re gonna stop the fight, stop it when I’m fighting, not resting.’”

A few fights later, Jaco beat Ruddock but the writing was on the wall He was relegated to the role of a globetrotting opponent, losing to Pierre Coetzer in South Africa, Tony Tucker in Monte Carlo, and a young, rampaging Mike Tyson in Albany, New York, in January 1986.

“I got a call a few days before to fight Kid Dynamite (Tyson) for $5,000,” said Jaco. “I said ‘Hell, yeah’ because that was a lot of money to me.”

All Jaco remembers of the fight is Tyson firing punches from all directions.

“I got up from a knockdown and the ref was waving the fight over. I asked what he was doing, and I reminded him of the three knockdown rule. He said I just used all my knockdowns up. I thought I only went down twice.”

Jaco’s fight against Tyson was his most important, for more than the obvious reasons. He arrived in Albany penniless, but took his earnings to Florida where he fought gamely to win custody of his sons from his troubled wife. He managed to do so and has never looked back.

“I left a blizzard in Toledo and arrived in Florida where it was 75 degrees,” said Jaco. “I immediately tracked down my kids and took them for a few months. I was feeding them, taking them to the beach to play football and swim. I was being their father, which was more important to me than anything.”

“When I first met Dave, the only thing he was concerned about was his kids,” said Florida promoter Allan Hill. “He lived, breathed and would have died to get custody of those kids. He’s got the biggest heart of anyone I’ve ever met.”

Years later, he experienced even more joy from the Tyson fight. Because he felt that he was short-changed by the promoter, he snatched both pairs of right hand gloves used in the bout and donated them to the Florida chapter of Project Rainbow, a national charity for terminally ill children.

Unbeknownst to Jaco, his new friend Hill had bought them with the intention of giving them back encased in glass at some special time in the future. He did so at Jaco’s 50th birthday party.

“It was one of the best presents I ever got,” said Jaco. “There are no words to describe what that meant to me.”

Jaco’s nominal record doesn’t begin to describe what a good fighter he was. What he managed to achieve with relatively no effort—like going the distance with Douglas and McCall—is extraordinary. Jaco took the fight with McCall just weeks after McCall was rumored to have dropped Tyson in a sparring session.

Hill, who was his cornerman for that fight, still marvels at Jaco’s nonchalance.

“I’ve known Dave a long time and he’s the most easygoing guy I ever met,” said Hill. “McCall had been a sparring partner of Tyson’s, and rumor was he knocked Tyson down in the gym. None of that meant anything to Dave. Forty-five minutes before the fight, he said he was hungry. I told him to wait to eat until later, that we were fighting this killer in less than an hour. Did he listen? Of course not! He ate two hot dogs and drank two large cokes.”

“With relish, onions, mustard and ketchup,” added Jaco. “I was down about three times, but at one point I hit McCall with a right hand – my money shot – square in the face. Later, his trainer, Beau Williford, told me his eyes were kissing.”

Then there was the night in Bakersfield, California, in December 1988 when Foreman hit Jaco in the center of the back as he turned away from a punch. He thought his spinal column was crushed because the pain was so excruciating.

“George is a nice guy, but a dirty fighter,” said Jaco. “After he hit me in the back, I felt my only chance was to punch with him. But who can punch with George and get away with it? He got me on the ropes, but my head felt like a tennis ball getting whacked around.”

The losses aside, Jaco beat a Florida-based Swedish Olympian named Hakan Brock, who was being groomed for stardom by Angelo Dundee. He also blasted out a previously unbeaten Germany-based African named Michael (Big Boy) Simuwelu in one round in Düsseldorf in March 1988. Afterwards he celebrated at a local bar, where he was encouraged to go on stage and sing a few songs.

“I drank about a bottle and a half of vodka, and thought I was crooning the crowd,” he recalled. “While I was singing, I took a fall and took the band out with me. My head was spinning so bad that I vomited about seven or eight times. Somehow I made it back to my hotel, but slept through my departure time for my flight home.”

While living in Florida, where Jaco was employed as an appliance delivery man and a driver for sickly patients to medical facilities, he was very active in his sons’ lives. He guided them both to numerous amateur titles, and both Aaron and Adam enjoyed some success in the professional ranks.

Although Jaco incurred 97 stitches, a broken cheekbone, two broken noses and numerous fractured ribs during his whirlwind career, he is very happy with the way things turned out. He and his second wife, Wynnah, have four beautiful grown daughters, Kaleigh, Brittany, Madison and Sydney, all of whom are superb athletes.

He was also a longtime boxing coach at Manatee Police Athletic League. For a guy that never got any breaks during his boxing career, he’s living a good life now.

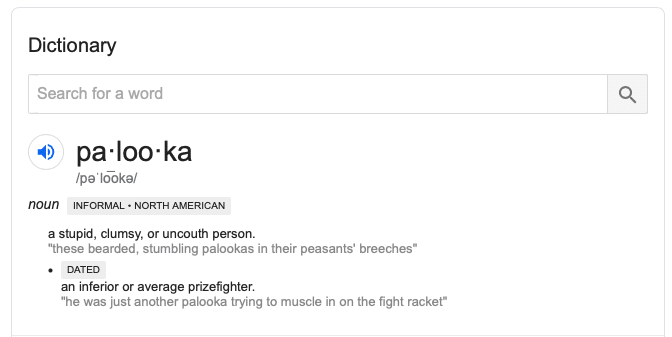

His exploits were chronicled in his wonderful and whimsical book, “Spontaneous Palooka,” which was published in 2012. He is extremely honest about both his skills and limitations, as well as his travels and travails. There is also no shortage of bawdy tales from around the world, as well as behind the scenes shenanigans from his more notable fights.

To know the colorful and likable Jaco, who was once profiled on ABC’s “Prime Time Live,” as a “Palooka” is a privilege. He is always smiling, extremely positive, and quick with a joke.

What is most obvious about Jaco is his allegiance to the people he cares for. Despite living a life more ordinary men might envy, at his core he is a family man with a big appetite for life’s simpler pleasures, mainly living well by laughing a lot, counting his blessings, and believing in himself through thick and thin.

Recalling his 1989 bout with Tommy Morrison, Jaco said, “They called me on a Monday night and had me fight Tommy Morrison on a Tuesday on ESPN. I was a palooka, one of those guys who basically goes in there looking for a big payday. I made thousands when I fought, but I didn’t consider myself a palooka. I was a decent fighter.

“I got my ass kicked, but I kicked some ass, too,” he continued.

“But I have a great wife, great kids, a great job and a new home. I never went to college, but made it through the school of hard knocks. You can’t judge a person by the color of their skin, their nationality, amount of education, or the size of the bank account. The best way to judge a man’s character is by the size of their heart. I’m not bragging or anything, but what I lacked in skill I more than made up for with heart. I’m very proud of that.”