Worldwide

Taking Harder Look At The Dismissal of Mark Breland From Team Deontay Wilder

Published

on

FEB. 9, 2021 UPDATE: He didn’t want to get deep into it when I got into on, but Mark Breland made up for it when he went on a streaming boxing opinion show called “The Fight Is Right” on Feb. 5.

The Brooklyn native, who gained gold at the 1984 Olympics and won crowns at 147 pounds while campaigning as a professional from 1984-1997, held his tongue with NY Fights in October, when the subject was him being let go by the Deontay Wilder team… but not TFIS. The hosts of the show are Spencer Fearon and Tunde Ajayi.

Breland told them how he sees his parting with Deontay Wilder now. “With Deontay and I, that’s a part of boxing I guess…His career is done now, so, I’m done and he’s done. I’m done with him,” the 57 year old stated.

A watcher asked if maybe if Wilder was now just in love with his power. “Well, one thing you all like to say is that, ‘He’s got a lot of power and that’s all. I wish him well and that’s it. All he got his power and we’ll see how far that takes him, that’s all I’m gonna say,” Breland said.

The show was hard to watch, because the hosts’ preambles were really long, and instead of asking Breland questions, they too often over-shared their own opinions. And Tunde sometimes works too hard to set the table before asking a “hard” question, and kisses ass too much, and it wastes time.

They got around to asking him if he thought Fury-Wilder 3 would occur, and Breland said, “I don’t think…I don’t care.”

He was asked about Wilder accusing him of spiking his water.“I mean, so many people know me, my character speaks for itself. ..Spiking the water? If you’re looking at the tapes or whatever, you don’t even see water in my hand,” Breland replied. “Someone else is giving him the water. And regardless of that, I’m there to help you. My attitude is, ‘When you win, I win.’ That’s the bottom line…I’ve seen some foolish people talking to me about that fight. Come on now, only foolish people come out with stuff like that because it’s crazy. If you know me, you know me.”

He said that it looks like Wilder just can’t handle losing. “Don’t blame everybody,” he said.

Part of the problem was that Wilder didn’t listen to suggestions, didn’t think he needed to add tweaks to the game. He then said he’d have beaten the guys Wilder fought, in fact.

You may have heard Wilder talking about how he thinks Tyson Fury had a foreign object in his mitts on fight night.

Breland said head trainer Jay Deas was “right there” when Fury was getting his hands wrapped, so loaded gloves are nonsense talk.

Breland didn’t hold back when the subject of Anthony Joshua came up. “I could beat Anthony Joshua,” he asserted. He’d outjab AJ, and “I don’t think he’d be able to touch me….From my eyes, what I see, I could beat him.” Naw, not today, he means back in the day. “He’s straight forward, not hard to hit.”

He likes Fury to beat AJ, for sure.

Hey, weren’t Wilder’s wins against Luis Ortiz solid? “You say he had some ‘good wins’? A good win. Just that fight, that was it.” He has no jab, Breland continued, he just used it once, in his first win against Bermane Stiverne. Oh, but his jab is better than AJ’s, he noted.

“No, he never hit the bag. He don’t hit the speed bag,” Breland said, shedding more light on Wilders’ work ethic. “He don’t jump rope, he don’t hit the speed bag and he don’t hit the heavy bag.”

And when asked how he thinks Wilder does moving forward, he told them he didn’t want to stay on the Wilder topic.

And, Breland was in a certain mood; he said he’s sure Pernell Whitaker would have beaten Floyd Mayweather. He was talking about Floyd, and some young guys coming up, when he said that he would have run the table if he’d been allowed to pick his opponents.

And yes, Wilder countered, he hopped on with 78 Sports TV and fired back.

“It’s crazy, brah, it’s crazy because I had this man around me for so long, my family, my kids, I fed this dude,” said 35 year old Deontay Wilder on Feb. 6.

“Even when many people thought I outgrew him. Many wanted me to fire him, but I kept him on board. …And to hear all these things that he’s saying, it’s crazy,” the ex champ said.

“It’s like, I’m the one that fed you, I’m the one that kept you around. You should have been gone a long time ago because of the love that I had, to continue to give you a job. Even after the fact with all the medical issues that he personally has going on with himself, I still kept him around.” BTW, he didn’t say what those issues might be.

“For him to betray me and say crazy stuff, it is a little hurtful only for these simple facts that how close I had him with my family, even playing with your kids, my first born, he used to play with her,” he said.

“But God is good…It just allows me to believe that he had something deeper rooted about me. I can’t understand what the fuck I do? …He knows what type of person I am,” he said.

“Where is it all coming from?” Deontay asked rheotically. “Is it because where I was in life and your career was short? It could be a jealousy thing. I can’t understand where it’s coming from.

Wilder is sticking by his contention that Breland doped him, drugged his water, for the record. He has no proof, but he says he knows anyway.

“I told Jay [Deas], ‘Man, I believe Mark did something to the water.’.. I’m telling you, I know how I felt in the ring, I was weak,” he said.

“This man been envious of me, he’s been jealous of me. Now this shit is all coming out. I told Jay, ‘Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer,” he said, and then rambled about how you should actually keep friends closer.

Wilder said that he sensed Breland’s energy wasn’t right in the first fight, “he was acting like he didn’t wanna be there….He left right after the fight was over with like he was mad or something. In the second fight, it was the same, his energy was off, he didn’t really wanna be around, like he knew something was up….It’s all good! He’s talking about the end of my career? It’s only the beginning of greatness. But for you my friend, it is the end,” said Wilder.

“I’m so glad I won’t die broke,” Wilder continued.

The host then said that it’s no concidence that in the UK heavy focus has been on MTK, but now UK figures made sure to make Wilder and his beef with Breland news-worthy again.

“He was definitely part of what was going on. His energy said it during the first fight, and in the second, it followed…I always speak about my people…You can’t break a king….A king knows how to get back up, dust himself off and continue to lead, because he understands he has people on the outside as well as the inside waiting on you to, “get up king! Continue to lead us, because we still follow, one by one, hurrah hurrah!” I’m a king. I know the responsibility that I hold in the world. I’m glad it came out. It all makes sense…The only explanation I can get out of it is, he was jealous of me and my career. Because I didn’t even have a relationship with Mark outside of boxing. Maybe he wanted to be closer to me. But he should know, I’m not that type of dude. I’m laid back, we talk when we talk. I don’t know what it is for him to come out and say all this shit all of a sudden, you put another man under the bus. So many people already ridiculed him, and doubted him.”

He said that it’s more complex now, with all the black vs white beefing going on. “The black man was wrong, he’s wrong for that shit. You did that to your own kind, n—-r. Like I said, I’m just so happy that I won’t die broke, so happy.”

The host tried to bring it back to the MTK doc, and corruption in boxing. Wilder didn’t take the bait.

Wilder said he gets extra negative attention, as opposed to others, not sure if he was talking about Tyson Fury, or what.

He said he stays positive, all the time. “Every day, I’m surrounded by love..hating a king like me isn’t going to do people in the world no good. It was a hurtful moment, just to see, certain things you just don’t want to be true.” He said sometimes it’s the ones nearest to you who hurt you most.

“He a bitch, he a bitch man, putting another man under the bus because you’re feeling guilty. Man up, you did the crime. Man up,” said Wilder. “It’s all good, nuthin but love. Wish him nuthin but well.”

See below for original piece, posted on Oct. 29, 2020…

********************************************************************************************************************

In the New York area, especially, former fighter Mark Breland, known in recent years as a trainer for heavyweight standout Deontay Wilder, is held in extremely high regard.

The Brooklyn-bred fight game icon who accumulated a 110-1 (73 KOs) record as an amateur and went 35-3-1 (25 KOs) as a pro, is seen uniformly as a decent soul. You’ll not hear a single bit of negative chatter about Mark if you ask around within the community.

The 57 year old has been since 2008 working with Deontay Wilder, the Alabama native who held the WBC heavyweight title before it was wrested from him Feb. 22, by Tyson Fury. In that outing, Wilder got worked over by Fury, who used a size advantage to take it to Wilder, and render the power in his right hand null.

Breland (below) drew attention to himself that night, for an act of supreme decency. He threw in the towel, and pulled the plug on the fight, in round 7, when Wilder (6-7, 230 pounds) was absorbing a vicious beating from the 6-9, 275 pound Fury.

The then 34 year old Wilder, though, didn’t appreciate that act of empathy, which, not to be hyperbolic, could have saved his life. He protested the stoppage and the post-fight press conference was dominated by the attention paid to the loser’s lament that he had told his crew and training team, Jay Deas and Breland, that if it ever came to that, he wanted to go out on his shield. They were not to throw in the towel, even if he was being battered unconscious. Or, to an unspoken-of ending, to death.

Advisor Shelly Finkel, who by the way served in the same capacity, managing the professional trajectory of Breland when Mark turned professional in 1984, and head trainer Deas, didn’t side with Breland that night.

The ex fighter was left by his lonesome, really, after exhibiting above and beyond decency. He wasn’t invited to the post-fight press conference stage.

After the Feb. 22 loss, even social media came to the defense of Breland, noting that he might have saved Wilders’ life. The fighter didn’t appreciate the gesture, however.

The other shoe from that “incident” dropped on October 2, when the 76-year-old Finkel told ESPN’s Steve Kim that Breland “will not be part of the team for the next fight.”

“I think things will switch around with the team that is there, with Malik (Malik Scott, an ex heavyweight who is friends with Wilder after being kayoed by Deontay in a 2014 contest) being in more of a role, and there’s not much more to it,” Finkel said to Kim.

There surely is more to it than that, but Finkel chose not to shed any light on the way the firing was handled.

But there is, actually.

When someone has been doing a job since 2008, and gets fired, and no reasoning is given, it leads people to be curious about the reason for the dismissal. Reading between the lines, fight fans might be thinking that there was or is something else in play, beyond Breland having committed that “infraction of kindness” Feb. 22.

Breland is a very soft-spoken person, decibel wise, and also in his manner. He’s not one to take to social media to air out a perceived aggrievement, for sure. I tried to call him after I saw the ESPN story, but the number I had for him wasn’t working. I messaged him on social media, asking him what happened, seeking some clarity on the move by Wilder, but didn’t hear back.

The abruptness, and the lack of clarity for the reasoning for the parting of ways struck me as rather cold, even for this sport, even during these times.

So I emailed Finkel, seeking clarity on the termination of Breland.

Sheldon Finkel, more so known as “Shelly,” moved from the rock ‘n roll space to boxing for his main gig as the 70s came to a close.

I saw you quoted in a story on Mark Breland being ousted from the team, my email read. Your reaction in the article I saw was short, almost curt, it looked like an “it is what is is” vibe. Being that you go so far back with Mark, that may not in fact be the case. Did you call Mark, give him the news….or did Wilder call Mark, who has been with you guys since way back? If there is more to the story, which didn’t emerge, that would be good to know. Mark is beloved, especially here in this neck of the woods, so I’d like to assure readers of NYFights.com that he was treated with the decency he deserves.

“No disrespect to you but at present I do not want to say anything,” Finkel responded.

The Brooklyn-born Finkel has known Breland since the early 80s; that pairing came onto radar screens of hardcore fans in 1983 or so. Before he turned 40, Finkel knew Breland would likely gain gold at the 1984 Olympics. A year or so before, he started setting up a plan for the Brooklyn fighter, who like Tommy Hearns, had a stringbean frame that could lure a bulkier foe into over-confidence.

Breland got the RING cover of the August 1984 issue, after enjoying winning gold on Saturday, Aug. 11, 1984 in LA.

Finkel ushered Breland out of NY, where he was trained by George Washington, and toward Detroit, placing him with Emanuel Steward before the Olympics. He was still seen as “rock-concert promoter” Shelly Finkel then, but he grew his rep hard and fast in boxing by snagging a piece of a marquee welterweight super fight, and then that much more with his roll-up of 1984 Games participants.

Finkel grew his negotiating chops, and how to craft contracts smartly, on the club scene and figuring out how the wheeling and dealing got handled at places like Action House, a groovy venue on Long Island, New York. Finkel makes a (mis-spelled) appearance in the cayenne-spicy biography from rock god drummer Carmine Appice, which conveys clearly the atmosphere in the hotel rooms the band partied in, and the back-rooms of some of the rooms they worked. His group, before he was in Vanilla Fudge, was called The Pigeons, and was managed as the 60s wound down by a nightclub owner, Phil Basile, who Appice said looked like Al Capone and was about as scary. Basile, Appice relayed, loved the hard thumping chops of the group. So, he sent “one of his people, Shelly Finkle” to get producer “Shadow” Morton to listen to The Pigeons, and consider working with them. Shadow wasn’t keen on it, but Shelly persevered; then in his early 20s, Sheldon got a limo and two bottles of whiskey and whisked Shadow from NYC to the Island. The producer dug what he heard and not long after The Pigeons and Shadow hashed out “You Keep Me Hangin’ On,” changed their name to Vanilla Fudge and had some luck on the Billboard charts.

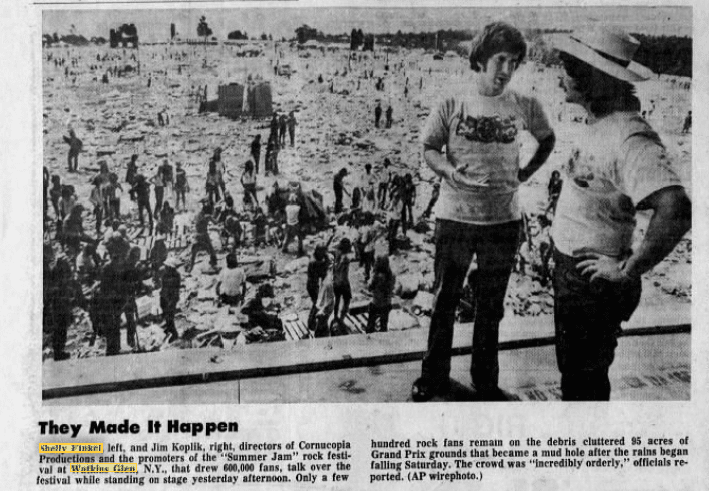

Finkel learned about some of those unwritten rules that are in play in some entertainment circles, and armed with knowledge he wasn’t finding when he dropped out of NYU, partnered up with Jim Koplik, another New Yorker, and promoted music gigs, working their way up to crafting mega festivals, with “Woodstock” as an influence.

Their “Summer Jam at Watkins Glen” show July 28, 1973 was the largest of its kind, according to Guinness, and you know that dealing with managers for acts like Led Zeppelin helped Finkel grow his muscles for dealings down the road in the pugilism arena. And mollifying county officials, that they’d not be out of pocket a cent despite the imminent influx of tens of thousands of high energy teens, that would also prove to be useful practice in convincing stubborn boxing folk to see things from the Finkel POV. Finkel had an unruffled personality; asked many years later, he pronounced the Jam a success, noting that no one died at the bash, except for the sky diver who was carrying an M-80 firework, or something of that ilk, which prematurely detonated as he descended from a plane over the crowd.

Willard J. Smith, age 35, from Syracuse, known as “Smitty,” wanted to do the drop and make an impact with the loud noise. Reports at the time said two flares he was carrying ignited and burned him, and that the detonation injured his chest and belly. By the way, reviews for the Jam were mixed. One teen was asked how the fest, which ran roughly from noon to 3:30 AM, was going, and said, “It’s like camping in a garbage dump and listening to a transistor radio.” John Belushi, pre SNL fame, attended and gazed out at the horde of youth. “You really have to wonder how crazy these kids can get,” he told a reporter. “They really look like they all might just kill themselves.”

The AP sent this pic of the two wheeler-dealers out over the wire for newspapers to use with a Summer Jam story.

By 1976 into 1977, Finkel was spending too much time, perhaps, responding to county officials’ asks and concert-goers who wanted to hear the tune-age but not pay for entry. Now operating as Cross Country Concerts, replacing the name Cornucopia Productions, and then Contemporary Concerts Corp., him and Jim placed more product indoors, and reduced their target zone, focusing heavily on Connecticut.

By the later 70s, Koplik stuck with the rock scene, and Finkel looked for a new turf to leave his prints on. In the summer of 1980, “rock promoter” Finkel was above-knee-deep in the fight racket. He’d aligned with Lou Duva, from NJ, and Johnny Bumphus, Mitch Green, Alex Ramos and Tony Tucker were in Shelly’s first batch of fighters.

Lou’s son Dan said that Finkel was putting on boxing shows in Hartford, CT, but losing money, and someone suggested he reach out to the team building up a base in Totowa, NJ. An interesting man named Dan Doyle, who at age 26 was trying to swing a deal to have the ABA basketball Nets switch home base to Hartford, was in the mix with Finkel and Duva. Doyle in a 1981 NY Times piece offered a different recollection on how him and Finkel crossed paths. While an assistant AD at Brown, Doyle helped a whole bunch of Sugar Ray Leonards’ fights. Doyle’s shiny rep got smudged when authorities nabbed him for embezzlement while acting as founder of the Institute for International Sport at the University of Rhode Island. He used more than $1 million from the nonprofit to pay for things like his daughter’s tuition, and a wedding rehearsal dinner. Doyle was convicted of 18 counts in December 2016 and is behind bars in Rhode Island, sentenced to serve seven years. Boxing folks do sometimes find themselves consorting with strange bedfellows, or doing business with people who possess admirable drive and ambition, but also the inclination to freelance outside the lines of the established parameters.

By the early fall 1980, Shelly was making noise, talking about having financial backing of the caliber that would allow him to have a hand in A-level fare. “I am ready and waiting to give Roberto Duran $10 million for a fight with Sugar Ray Leonard,” he told press in September ’80, regarding a second SRL-Duran tango. “The offer will only be good next Tuesday.” Yes, he was still transitioning from the rock scene, to boxing, where people are even more inclined to tell you to GFY with that sort of dwindling time offer.

In 1981, Finkel wanted a piece of a Thomas Hearns vs Ray Leonard pairing, and it was assumed by entrenched fat cats that he’d not suceed. Oh but he did. Finkel landed the clash because Mike Trainer, the Leonard advisor, was open to working with people other than the usual suspects, if that meant better terms for his guy. Fight fans needed to be introduced to him, and the head promoter for the Leonard-Hearns collision, the Duva’ Main Event, which became Main EVENTS when they realized they’d be able to do more large-scale deals. But insiders knew that Finkel was a major league ball-player, right then…and he’s stayed at that level in that league for the next 40 years.

Reminders from the rock days would pop up; in July 1982, a claim of negligence stemming from the Watkins Glen fest finally wiggled its way into court, with Finkel being one of the names on the suit accused of negligence.

But now, he was a boxing guy, and he asserted that one of the things that made him different was that he saw and treated the fighters as people, not meat. That was made clear when he told press how he’d made sure some annuities would kick in for Breland after his fighting time came to a close. In the boxing realm, Shelly would have to deal with problems, sure, but not like that festival suit, which was lodged by people who said that four of their pigs were stolen off their farm by fest-fiends.

The fourth of six kids born to Herbert and Luemisher Breland, the Bed-Stuy guy Breland by early 1982 was the top ranked welterweight in the amateurs. His buzz was building, that summer he’d go and do filming for the film “The Lords of Discipline,” while building a rep as best-kown amateur in the states.

“Discipline,” based off the novel by Pat Conroy riffing on his time at The Citadel, the military college, came out in 1983.

Finkel wasn’t allowed to sign Breland, and wasn’t allowed to pay him, but moves he made benefitted the young man. He told press that he’d invested heavily in Breland, flying all over the world to Brelands’ fights leading up to the Olympics.

Mark accumulated five NY Golden Gloves win, and won gold in ’84, as part of a superior team, with Tyrell Biggs, Pernell Whitaker and Evander Holyfield. Americans grabbed nine golds at a Games that didn’t enjoy the prticipation of the Russians and Cubans, who blew off the event in Los Angeles, as political payback for America doing so in 1980.

Expectations were higher than the Empire State for Breland after he easily hammered South Korea’s An Young-Su; Ray Arcel told people Breland reminded him of Sugar Ray Robinson. The kid maybe at times thought too much, understandably because of those expectations. Finkel watched and weighed in, and steered, with Lou Duva, as Breland attached to Main Events, then run by Dan Duva. And Finkel did a good job, outside looking in. Breland debuted on Nov. 15, 1984, at Madison Square Garden, along with Virgil Hill, Tyrell Briggs, Meldrick Taylor, Pernell Whitaker and light heavyweight Evander Holyfield. Tix were free, it was said that Mark bought every ticket with his own money and handed them out, and 18,000 hit MSG to see the young guns get off the block. After six rounds, Breland bested 7-1 Dwight Williams.

Breland went 7-0 in 1985, and 8-0 in 1986. This is boxing, though, and it is damn near impossible to keep everyone happy. People wanted their pound of flesh, and write-ups would feature critiques galore if Breland didn’t score a stoppage in a win. Managerial and promotional steering, and Breland’s chops led to a title, the WBA 147 crown vacated by Lloyd Honeyghan, which Mark snagged in a Feb. 6, 1987 contest against South African Harold Volbrecht, by stoppage.

At 16-0, some thought he was the best 147 then active, but after a gimme defense against Juan Rondon in Italy, Marlon Starling arrested the title reign, in round 11 of their Aug. 22, 1987 scrap. And it was said that Mark came in to that fight with a busted rib, but decided to fight through the injury.

The ship was steered, by Finkel and company, to a rematch with Starling, which ended in a draw. It wasn’t uncomplicated before, but at this level of competition, with the money and acclaim in play, it got stickier, even. Breland sometimes felt sick of the sport, and some counseled him to leave the sport.

“No manager ever loved a fighter the way Finkel loves Breland,” that was what Michael Katz wrote in the NY Daily News in February 1989. And part of the love was skillfull steering; in 1989 Breland beat up a faded Seung Soon Lee, not an A sider type to begin with, and won the vacant WBA welter crown.

He did defenses, against solid but not stellar Rafael Pineda, a wisely manuevered Swiss native named Mauro Martelli and Japan’s Fujio Ozaki, a sub Hall of Famer who retired after Breland smashed him up in round four, in Japan. That was his sixth KO win in a row, and brought him to a clash with Brit Lloyd Honeyghan. Breland tested and bested Lloyd’s chin from the start and achieved a stop in round three.

That triumphant buzz ceased when he got stopped by Aaron Davis, off a looper right hand he walked into. It sent him down, for a ten count, where he stayed for a couple scary minutes. After, Finkel was quoted in the papers saying he loved the kid, and he hoped he’d retire, and that he could join him in scouting for young talent.

“I just love him. It just kills me to see him get hurt,” Finkel told Katz the night of the July 1990 loss to Davis. Four fights came after that, at middleweight, and Mark hung up the mitts after a Sept. 1991 stoppage loss to Jorge Vaca. In 1996, he returned to the fray, winning five more contests, and that got live fighting out of his system. In 2000, he started working in a trainer capacity, a shift that came with Finkel as a catalyst and usher, and we saw him working with Anthony Hanshaw, Johnny Molnar, Dominic Guinn, Jorge Teron, Vernon Forrest, Henry Crawford, and then with Wilder.

Year after year, he tried to get the Alabama boxer to heavily employ the jab that USA Boxing testing scored as powerfully as most heavyweights’ power punch, and had mixed success. Wilder, in the last couple years especially, fell in love with the idea of being that one-hitter-quitter guy, and no one could get him to switch the mindset.

Only those deep inside that camp could tell us more about all that. People with true knowledge of the dynamics in play there, and how Wilder did or didn’t progress like he should have, and how much his own point of view and conception of what sort of fighter he was, they understand how much who trains him contributes to his winning and losing, at this juncture.

You may have picked up on a change in how Wilder comported himself after he beat Luis Ortiz, the 40 or so year old Cuban heavyweight, for the second time, on November 23, 2019.

Here’s what I wrote in a “Takeaways” column after that win:

“More man and woman hours are spent on social media debating the unknowable, the un-provable, and what if we all decided to not argue that of course Hearns, Shavers, Foreman or Liston or whoever the hell is a harder hitter than Wilder? Because we can never know. Unless they find a way to measure power, during a fight, and then be able to employ the tech for fights on film, we’ll never know.

“He’s the biggest puncher not just in heavyweight history, but in boxing history,” Tyson Fury trainer Ben Davison said when asked where Wilder sits, power-wise, among the sport’s greats. Un-provable, but this we can say: Wilder punches like a mule that got into the Mexican meat kicks, let’s leave it at that. VF hard!”

A little narrative surge formed after that win, and people debated if Wilder hit harder than ANYONE, EVER. And he bought into it, even more than he had before, how hard he smashed. And no, that didn’t help out anyone trying to get him to see that a snappy jab thrown from 36 inches away could be winning him rounds, before he decided to drop the “2.”

You didn’t see that jab in the second fight against Tyson Fury, you saw Fury bullying Breland at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, backing him up, his ultra-savvy game-planning paying off in round three when he sent Wilder to the floor. And again, in round 5. Breland knew what he was seeing, maybe, honestly, better than any other person in that room. That’s not hyperbole, he’d been there, in that dreadful place, when you have no answers, and the hard rain of hands is piercing your nonexistent defense. He held his worries to himself, when he saw blood coming out of Wilders’ left ear after round three ended, but started doing considering going against Wilders’ directive, for his own damn good.

In the seventh, Wilder couldn’t find enough air to feed his tired body, and, backed in a corner, he was eating shot after shot. Enough, Breland thought to himself, if Kenny Bayless won’t pull the plug, I will.

Breland threw in a white towel, and out of the corner of his eye, the ref saw it, and stepped in.

Wilder, who has eight children with four different partners, wasn’t too pleased, but he was, and is, alive. Maybe one day he will have enough space and time to ponder, and instead of being content he fired Breland, he will thank him, for maybe saving his damn life.

“The best man won tonight. But my trainer, my coach, my side threw in the towel, and you know I’m ready to go out on my shield, man,” Wilder (42-1-1) said after, in-ring to Bernardo Osuna. “I just wish that my corner woulda let me went out on my shield, I’m a warrior, and that’s what I do, you know what I’m sayin? But he did what he did, it’s no excuses, and we come back and we’ll be stronger.”

Osuna, bless him, said, “they did something to protect you, which is their job, which is important,” showing he has a full handle on proper big picture considerations.

In the post-fight scrum, Breland, and Finkel and Jay Deas (below) and Wilder were grilled about the ending. “Mark threw the towel, I didn’t think he should’ve,” the Alabama resident Deas told reporters at the after-fight presser.

“Deontay’s the kind of guy that’s a ‘go out on his shield’ kinda guy,” he said, “and he’ll tell you straight up, don’t throw the towel in.”

After Deas spoke, Finkel was asked if he’d like to weigh in. He had a look on his face throughout this post-fight session like he’d left his lunch in the fridge at work, and had just discovered some miscreant had stolen it. He spoke, as on the other side, Fury and co-promoters Bob Arum and Frank Warren listened in, but he didn’t touch on the white towel being thrown. He lauded Fury’s ability, said Wilder will take some time, and that, “You will see these guys in the ring again.” Yes, it was about business, in that moment, more than about the human condition, about love and loyalty and the true meaning of that term.

A text message sent Oct. 13 to Deas, asking him about who broke the news to Breland and seeking more information on the parting, went unanswered.

Breland, to reiterate, very much didn’t want to get into particulars right after the fight, or more recently. I reached out the week following the Wilder loss, because, to be very up front, I didn’t care for how Breland was being thrown under the bus, in my mind, for his merciful action. He didn’t return a couple voice mail messages.

Wilder a couple days after the loss said he still loved Breland but that he wouldn’t be part of the team going forward as a result. “I am upset with Mark for the simple fact that we’ve talked about this many times and it’s not emotional,” Wilder said to Kevin Iole. “It is not an emotional thing, it’s a principle thing. We’ve talked about this situation many, many years before this even happened. I said as a warrior, as a champion, as a leader, as a ruler, I want to go out on my shield. If I’m talking about going in and killing a man, I respect the same way. I abide by the same principle of receiving.” He then told Lance Pugmire he was still evaluating whether to keep Breland. And on Feb. 29, he posted a bizarro home video. “Your king is in great spirits,” he told fans, promising he’s still of a mind to fight to the death and that he’d regain that WBC title. Clearly, he was still at a place where his emotions were aswirl.

Wilder did say he didn’t want to offer excuses, then told people that he came in with a hurt leg, and also that his energy was sapped because his ring-walk costume was too heavy. “He didn’t hurt me at all, but the simple fact is … that my uniform was way too heavy for me,” Wilder told Iole two days after losing. “I didn’t have no legs from the beginning of the fight. In the third round, my legs were just shot all the way through….I knew I didn’t have the legs because of my uniform….I was only able to put it on [for the first time] the night before, but I didn’t think it was going to be that heavy. It weighed 40, 40-some pounds with the helmet and all the batteries. I wanted my tribute to be great for Black History Month. I wanted it to be good and I guess I put that before anything.”

He was roundly mocked, deservedly so, for that ludicrous attempt to explain away how it wasn’t simply that maybe he got too cocky with his power, didn’t train for 12 hard rounds, isn’t ever seen doing road-work and that Fury was the better man Feb. 22. And now, if he wants to edge away from the costume excuse, he can do this silent condemnation, implying that his team wasn’t set properly. Or he can do the right thing, tell the press that he owns that loss to Fury…and how about giving Breland a call to thank him for his service, too?

Breland stayed quiet through all of that nonsense. And he stayed silent when the dismissal was announced, in an ESPN story. The number I had for Breland now didn’t work, and a Facebook message I sent didn’t get a response.

After some more gentle journalistic prodding, though, Breland provided me this answer, when asked how he felt about being let go, after 12 years, and for clarity on how the firing was handled.

“I am disappointed,” Mark Breland said to NY Fights, “that Shelly didn’t reach out and speak to me, before he talked to ESPN.”

Founder/editor Michael Woods got addicted to boxing in 1990, when Buster Douglas shocked the world with his demolition of the then-impregnable Mike Tyson. The Brooklyn-based journalist has covered the sport since for ESPN The Magazine, ESPN.com, Bad Left Hook and RING. His journalism career started with NY Newsday in 1999. Michael Woods is also an accomplished blow by blow and color man, having done work for Top Rank, DiBella Entertainment, EPIX, and for Facebook Fightnight Live, since 2017.

You may like

-

Friday Recap: Jaime Munguia Body Blasts Take Down Erik Bazinyan In Ten

-

5vs5 Boxing: Zhang, Dubois Seal Team Sweep

-

Weigh-In Results: 5vs5 Boxing Tournament

-

Fight Recap: Lomachenko Lays Down The Law, Defeats Kambosos Jr.

-

Where To Watch The Next Chocolatito Fight

-

Yokasta Valle Ready to Rumble Friday With Seniesa Estrada