There was a time about fifteen or sixteen years ago when I felt my life changing in a way that meant I was moving from one stage and into another, going into whatever comes after youth.

I wrote up how I was feeling in a piece for an obscure website and published it under a username, saying, “The saddest part of growing up and becoming responsible is not the death of the little things that used to make up your life but the knowledge that the person you were has gone forever, disappeared before you know how to be the person you’re going to become.”

That was when I thought I was approaching new things or, at least, straining against the limits of my ignorance.

I was wrong. The great career I was heading into never happened. I fell off the ladder two years into it, went to Berlin, and have been there ever since. It turned out that the little things that I thought had to die had other ideas.

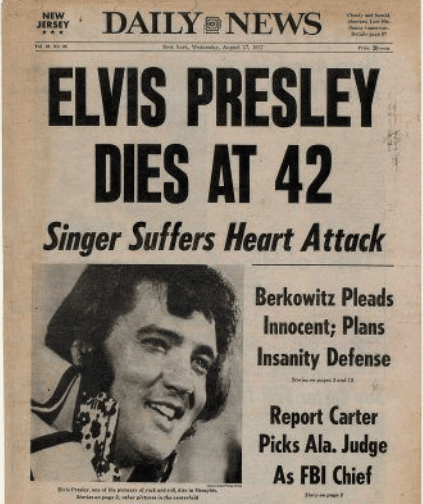

And then I turned forty last year, which seems to be a milestone age. No one seems to say why. It may be that it marks the point at which youth really ends and you are supposed to have it together (if you are ever going to have it together at all). It may be an appreciation that you made it this far, a year or so past medieval life expectancy; eight more than Jesus; two to go before you surpass Elvis.

It may even be an acknowledgement that you are at the halfway point, which presumes exactly when the end will be. Eighty? Time for you to go, sir.

But I have found that where life seemed to do nothing but give me things in my first four decades, it has now begun taking them away.

I am at the beginning of the end, as it were.

This last year has seen two of my friends die. They were older than me, although not by much. I met both when I was a student, over twenty years ago, one in my first year and the other in my third. I am not using their real names here and have also adjusted or obscured some identifying information, lest their memories become tainted by our association.

Their names were Davis and Clark. I met Davis first. He was a few years older, a mature student studying amongst those of us who had mostly stopped being children.

I never knew much about Davis’s background or why he had only gone on to study for a degree in his mid-twenties. Or if I did once know about it, those memories have faded. He studied the same course I did, and we graduated at the same time.

We were not close friends. I never knew the inside of his house or his heart. We never socialised more than grabbed drinks between lectures. There were no birthday cards exchanged and no hope, really, of staying in touch after graduation. But I considered him a friend.

My last real and true memory of him was the day that we submitted our dissertations, the final piece of writing to mark the end of three years. Davis, as he always did, had written much more than he should have—a habit that I think had gotten him automatic passes over the years when tutors saw the brick-sized documents that would be trundled into their offices, and said, “Fuck it. I don’t have time for this.”

It was raining that morning (and it seems when I remember things that it was always raining at the time) and we were printing in the computer rooms. Afterwards, we went outside to talk. Davis approached, his dissertation in hand, so thick that the two fingers pinching it together were a good inch apart.

He stopped about four feet from the rest of us and looked down. His face twisted and grimaced.

“Are you okay?” someone asked.

“No,” he said, trembling. He pointed to a spelling mistake in the footer of his work. The same mistake that now ran through the rest of the printed document, all 120-plus pages of it, imprinted like one of those messages in a stick of Blackpool rock. “It’s all fucking shit!” he yelled in frustration, turned, and with a throw worthy of the NBA, sent his entire dissertation flying into a nearby bin.

Or nearly the entire thing. A single piece of paper landed on the ground, stuck to the damp concrete. The spelling mistake winked up at him. He kicked at the paper, but it would not move, stuck fast. I had never seen an inanimate object smirk until this moment. Davis kicked at it again and scuffed it and ripped some of it into strips, but the thing remained there, taunting him with its mere presence.

We left him outside that room, kicking impotently at the floor.

When I think of Davis, I always think of him in tandem with a mutual friend called Gary. The pair never lived together, and had not been friends before, but seemed bound to each other through those years.

It was Gary who reached out to me late in 2021. “Hey, Pete,” he wrote, “Hope you are okay. I don’t know whether you are aware but thought you would want to know—Davis died last week. Awful news—it came out of the blue and terribly sad. He had a brain aneurysm and died suddenly. He was one of the good guys. Funny as fuck, too.”

The second friend of mine to have died in such a sudden manner recently was my friend Clark.

I met him in the third year of university, when I started a new job, and he was the supervisor. He also, coincidentally, lived around the corner from me. Clark was older than Davis, a former professional footballer training to be a teacher. The memory is faded again, that once-vivid print bleached and whitened, but he was somewhere in his mid-thirties when I met him. He shared an apartment with Lucas, another friend of ours.

I was arguably closer with Clark than I was with Davis. I had broken up with my first serious girlfriend a few months before and was lonely and so I spent a lot of time hanging out at his place with he and Lucas.

I found out he was dead a few months ago. It was a surprise. He had gone, slipped away, without anyone knowing of it. I saw something and someone that reminded me of him, and I went to check his Facebook page on a whim, only to find a note from one of his friends to say that he had passed some weeks before.

There were other posts, too, public ones that announced the passing. I contacted Lucas, with whom he had lived for three years, and broke the news to him.

We spoke to other people. Lucas got in touch with a mutual friend of he and Clark’s, and that friend told him that Clark had had cancer, but had been planning trips throughout 2022 and into 2023. I messaged one of Clark’s more-recent friends and they messaged back, sending me to someone else who said that the family were choosing not to say how he had died. A month had elapsed between the death and the service.

I do not know for sure, but I think that the cancer had come back and there was nothing that could have been done this time. And Clark, seeing that in front of him was only decline and pain, took the decision to go out on his own terms.

I would have wanted to say goodbye, to have gone and seen him. We could have talked about the old times, about all the things we did and of all the people that we knew. But I suspect that he would not have wanted that. A man rich in love for life and not ready to go does not want to be reminded of what he is leaving behind.

There is a friend of mine, someone I have known for thirty years, and he is a priest and we talk sometimes around the subjects of his faith, even if I have no great belief in God, other than to not trust any deity who would let someone like me join her club.

I told the priest what I thought, that Clark had made the decision to go out with some strength left in his body before it failed him. And the priest said that it was common, that those who are that sick often make that choice.

There is one last good memory that I have of Clark. In 2008, four years or so after graduation, I was working in London. One night, I was walking from the office in which I worked, through Leicester Square, to take the bus home, when I saw him out of the corner of my eye.

I turned, ran, and caught up to him. We were both surprised that the other was there. We hugged, inquired briefly about the others’ life, and then went our separate ways, he to his dinner reservation and me to home.

And then, a few months ago, he was dead. And it hit me hard because it was only after he was gone that I knew that I had loved him. It is a difficult, tough thing to realise that you love somebody. And it is hard to lose somebody about whom you feel that way, especially when you did not know, before they were gone, that you loved them.

Neither of them left much behind. They did not have children, had had no great careers, produced no great works. Their lives after death as anonymous as they were before it.

And yet there were both good men. And a good man should always be remembered, even if the only memorable thing about him was that he was good.

I went somewhere quiet when Davis died and raised a glass and thought about him. I did the same ten years ago when my friend Braden died. I will do the same for Clark at some point. And I will do it for the next friend who goes and the next one and the one after them. Hopefully, one day, someone will do it for me.

And I think sometimes about where the years have gone, and along with them those moments that we never chose to remember, but somehow did, and now they are the only things I think of. And those moments one day will themselves be lost forever.

And then I remember to enjoy it all, every last stinking minute of it all, the good and the bad. Because the trick is not to appreciate it when it has gone, but while it is still in the here and now.

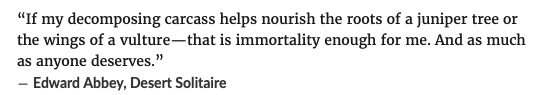

The great American writer Edward Abbey died in 1989, done in, it seemed, by genetics and hard living. His death and its aftermath became its own legend as he was buried secretly, in a hidden location, somewhere in his beloved American southwest.

Not long after, his friend David Quammen wrote about that end. Abbey had told Quammen in a note that he wanted ‘a big happy raucous wake’.

Quammen went on: “He wanted more music, gay and lively music. He wanted bagpipes. ‘I want dancing! And a flood of beer and booze!’ and a bonfire, said the message. And people making love. And meat, lots of meat. Beans and chilis! And corn on the cob. Only a man deeply in love with life and hopelessly soft on humanity would specify, from beyond the grave, that his mourners receive corn on the cob.”

Even in his death, it seemed Edward Abbey wanted to celebrate life.

We should all be so lucky, thought Quammen. We should all live and die so well.

There is no great trick. This is no new advice. Twenty-five years after Abbey died, his fellow desert rat, writer, raconteur, and cult legend Charles Bowden met his end, sixty-nine years old and done in by the flu, that final blow coming after decades of living on the edge. It was, some suggested, an unnatural death for Bowden—the end seemingly promised and prophesised for him of a bullet from a Mexican sicario.

Less than a year after he died, the writer Richard Grant reflected on Bowden’s death in the light of the latter’s essay ‘The Bone Garden of Desire’, written for Esquire in 2007.

Grant wrote of Bowden: “When your friends are dying, he advised, go into the kitchen, cook well, savour the flavours on your tongue. So I lay the yellow peppers on the blue flames of the stove, and start chopping the onions, carrots, and other vegetables.”

My friends are gone and will not come back. An easy thing to accept, if not to know. They have gone on to wherever we go—if we go anywhere—and now make their homes among the stars.

No point in further tears.

Life goes on, as it were, until it does not. Enjoy it.

Read more from Pete Carvill here