LAS VEGAS — In the summer of 2020, J Santos landed his first significant job. He had just turned 18, and thought he should find an opportunity to work in the sport where his father had been making a living for the last three decades. However, Santos was seeking a less physically demanding gig than his amateur career, which ended unceremoniously as a 12-year-old when his braces began to rip off his gums, resulting in career-ending surgery.

“Yeah, I ended up having to get gum surgery, which wasn’t the most fun,” he laughed.

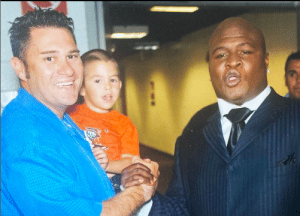

After graduating high school from Valley Christian High School in San Jose, California, in 2019, Santos, the son of renowned boxing trainer Bob Santos, moved to Las Vegas to run training camps for his father.

No problem, he thought. The task seemed so much less daunting than taking punches to the face. On the other hand, Santos—the “J” subs in for “Joseph,” by the way–wasn’t aware that he’d also be doubling as a cutman.

“Cuts was not exactly what I had in mind. The first corner that I worked, I wasn’t expecting to work cuts, but I guess that’s what they needed in the corner,” recalls the 21 year old Santos, already accustomed to the grind of boxing following his brief amateur career.

Then a lightning bolt ignited in his brain, a breakthrough moment. And with it, Santos rose to his feet and exclaimed, “This is just like being in that ring!”

At boxing’s elite levels, fighters can make adjustments on the fly. When a cutman was needed for twin fighters Angel and Chavez Barrientes, Santos was expected to fill that void. Not only was he successful, but it also opened up a floodgate of potential opportunities for Santos.

“It started with the twins, and it has led to working with guys like Hector Garcia, Alberto Puello, Carlos Adames, Michel Rivera, Victor Santillan, Ariel Perez, and Kevin Brown.”

While such an impressive inventory of fighters within a two-year timeframe may surprise many, don’t consider his father one of them.

“He’s always had a God-given ability to decipher things very quickly,” he stated. “I liken it in a way to how I started in this business with [legendary boxing manager] Louis DeCubas Sr. and his son Louis DeCubas Jr. ascending as one of the premier power figures in the sport, along with Al Haymon launching Premier Boxing Champions.

“It’s almost similar in the sense that he’s following in the footsteps of Louis DeCubas Sr. and his son. Obviously, Jr. has taken it to a whole new level with the accomplishments he’s had with [former super middleweight titlist] Caleb Plant, [former two-division world champion] Robert Guerrero, [former 154-pound titleholder] Erislandy Lara, and the list goes on. There’s a lot of similarities to Louis DeCubas Jr., and to me, I hold that in the highest regard, and that’s the best compliment you can pay somebody.”

A solid nickname for the youthful Santos could be “a J of all trades.”

“I don’t want to be in one position for my entire career,” he laughed. “Outside of cut work, I also help my dad with nutrition and running the full camps. I am knowledgable of different aspects of the sport, but when I do work the corners I am a cutman.”

He’s not a zealot. He’s not Twitter famous and admittedly resembles a Nickolodeon character (Danny Fenton; see below). But he does stand for something.

“Hard work,” he says, “that’s how you make it, and somewhere along the way, you may just get lucky.”

When asked to provide specifics, Santos took NYFights on a deep dive into his childhood and how one night in Las Vegas reversed the odds.

“I grew up in a bad area of San Jose for the first 15 years of my life,” he revealed. “Then my dad started working with Robert Guerrero and, of course, he ended up fighting Floyd Mayweather Jr. [on May 4, 2013], which changed our lives — literally overnight.

“We bought a new house, which pushed me through private school, and it changed our lives. So my message for the youth, I know it sounds cliché, but realistically stay focused on what you want in life. At the end of the day, no one is going to get for you, nobody is going to do the job for you, but I guarantee if you stay focused on what you want, you can definitely achieve it. Regardless of who you are and what you want to do, if you really put your full effort and focus into that, you can do it.”

Santos was no Mayweather fan in his youth, but admits his interaction with the unbeaten former five-division world champion in the buildup to the Guerrero fight permanently changed his perception of “Money.”

“I had never met him [before the Guerrero fight]. He seemed arrogant at first. I judged him based on what I saw on TV, but when I met him in person, he was very cool and respectful. I wasn’t exactly someone he needed to be nice to, so that was very cool of him.

“It’s funny because moments before we met, he was talking all of this crap to Robert, but it was just a part of promoting the fight. Obviously, he was a masterful fighter and incredible at psychological warfare. The mental aspect of boxing is more important than many people realize, and he knew how to get in your head and mess with you.”

The Santos family is one of many working to keep boxing alive and vital in the United States. They never got the memo—circulated erroneously for decades—that the sport is dying or on its last legs.

“Well, let’s get this out of the way. I definitely don’t want to be in the cutman hall of fame,” Santos laughed. “But yeah, right now my pops is a candidate for 2022 Trainer of the Year [for wins with WBA “regular” junior welterweight titleholder Alberto Puello (21-0, 10 KOs) and unbeaten southpaw Hector Garcia (16-0, 10 KOs)], which is incredible. And I want to go on my own path in this sport, but I see myself somewhat following in his footsteps.

“But ultimately, my goal in boxing is to make my own legacy. Whether that entails a Trainer of the Year award or a Hall of Fame induction at the end of my career, as long as I can have a positive impact on these fighters’ careers and give my God-given best to them, then I’m happy with that.”

By most measurements, Santos is just a kid, but he’s just a pillar of the future of boxing. It’s been this way throughout history, going back centuries. The old guard can’t be around forever, and eventually the torch will have to be passed on. Now as ever, the youth remains the hope of our motherland and our sport.