When Roberto Duran waved his hands in resignation and quit in the rematch with Sugar Ray Leonard 42 years ago, it appeared the rivalry with the American superstar was effectively over. A champion of folk hero proportions in his native Panama and everywhere else just moments earlier, Duran became a pariah with the utterance of two Spanish words: “no mas!”

Not only was there no interest in a third fight with Leonard – there was little interest in Duran at all. From there, the Panamanian’s career plummeted to profound lows, as the man with the “Hands of Stone” lost a decision to ordinary Kirkland Laing in 1982 – a lowlight that convinced promoter Don King to get rid of him. Meanwhile, Leonard’s fortunes weren’t much better, as he was forced to retire months later because of a detached retina.

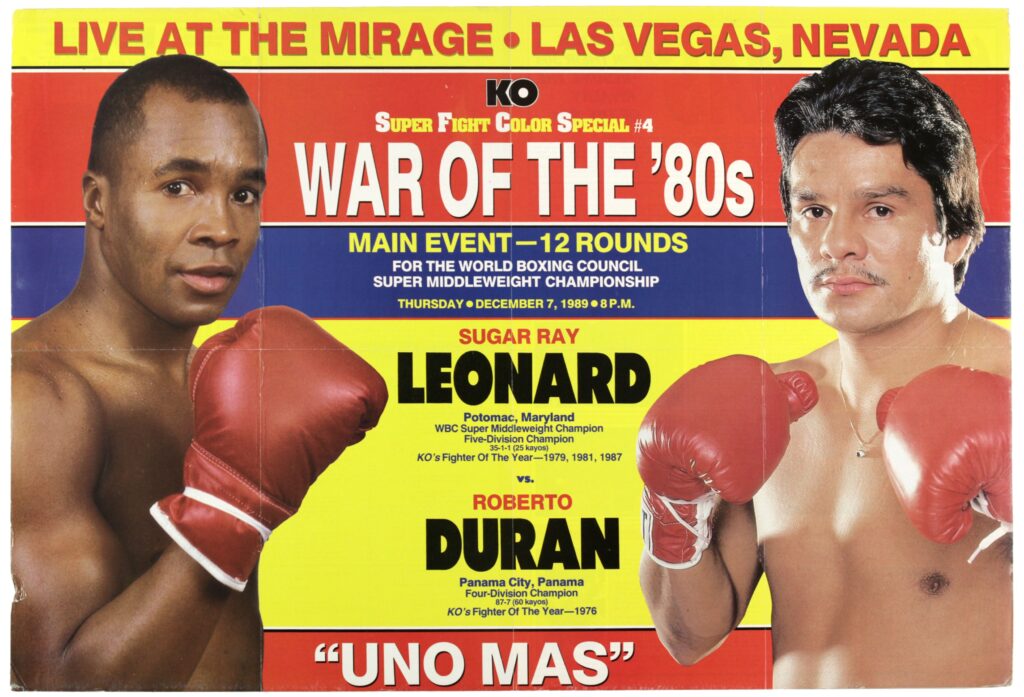

If you’d told the world in 1982 that Duran and Leonard would fight again in 1989, the world would have laughed at you. Yet, it was an unlikely confluence of life events (Duran signing with Bob Arum, Leonard returning from eye surgery) and miraculous late-career heroics (Leonard upsetting Marvin Hagler, Duran shocking Iran Barkley) that magically turned a third Leonard-Duran fight from impossible to possible – a whopping nine years after their rematch.

Like Leonard and Duran, Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and Gennadiy “GGG” Golovkin have gone through their own implausible, topsy-turvy journey to a rubber match. Four years will have passed from the 2018 rematch to Sept. 17, when they square off for Canelo’s undisputed super middleweight titles at T-Mobile Arena.

It’s not every day that there is such a long gap between the second and third fights of a trilogy. Only two years elapsed between the second and third Marco Antonio Barrera-Erik Morales fights. There were mere months between fights two and three of the Chiquita Gonzalez-Michael Carbajal series. And Micky Ward and Arturo Gatti fought their entire three fights in a span of 13 months.

We’ll see if four years is worth the wait for Canelo, 57-2-2 (39 KO’s), the Mexican from Guadalajara, and GGG, 42-1-1 (37 KO’s), the Kazakhstani from Karaganda.

As recently as early this year, with Canelo coming off a smashing knockout of Caleb Plant to reaffirm his status as the (then) best fighter in boxing, a third installment of the GGG series didn’t appear likely, or even necessary. For years, some boxing fans argued that Canelo needed the third fight with GGG to reaffirm his greatness, as the first two fights were inconclusive at best.

Ultimately, that argument became stale. Canelo was fighting too well, GGG was looking too worn, and interest in a trilogy became virtually nonexistent.

Improbably, we’ll now – finally – get closure in a series that featured an infamous draw (Sept. 16, 2017, a.k.a. the fight that made Adelaide Byrd the most notorious judge on the planet) and a spirited, disputed Canelo win by split decision (Sept. 15, 2018, a fight that featured an overwhelming majority of the ringside press scoring it for GGG).

All three fights will have taken place on Mexican Independence Day weekend. And all three fights will have taken place at T-Mobile Arena.

Like Leonard-Duran 3, Canelo-GGG 3 is supposedly years past its buy date. Some might even classify it under the “Better Never Than Late” banner. But sometimes pairing old rivals turns out well regardless of when they are matched. The classic example is Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, who turned in arguably the greatest fight in boxing history in their rubber match (the classic “Thrilla in Manila”), despite both being past their respective primes. Riddick Bowe-Evander Holyfield is another example of a series that was great regardless of when they were matched or whether they were in their “primes.”

More recently, Tyson Fury and Deontay Wilder proved that, regardless of time or date, they will always make for a brutally compelling evening.

The flip side was the needless trilogy between Manny Pacquiao and Erik Morales, in which Morales grew old in the rematch – and even older in the third fight.

What makes Canelo-GGG 3 similar to Leonard-Duran 3 in particular is the palpable animosity. Duran hated Leonard, much like Canelo hates GGG. For Duran, Leonard represented American privilege – a pretty boy whose road to the top was paved smooth thanks to a gold medal won in the 1976 Olympics and a formidable marketing machine that came with it. For the hard-scrabble street fighter from the streets of Panama, Leonard represented everything Duran detested. Duran turned that dislike into such a raging inferno that it fueled his June 20, 1980 victory in the original Leonard fight – one of the most impassioned performances in boxing history. Duran was a hungry beast of a fighter that night, intent and determined to defeat his bigger, faster, more talented foe. And he did, by majority decision.

Canelo resents GGG in much the same way, because of what he interprets as GGG’s superficial “nice guy” personality. He reads him as someone who appears congenial and gentlemanly face-to-face but then hurls insults behind his back. He calls GGG a “sh***y” person and a hypocrite. He claims he is a jerk behind the scenes – right up until the camera lights go on.

Of course, the basis for GGG’s criticisms are of Canelo’s doing, as the red-headed Mexican tested positive for the illegal Performance Enhancing Drug Clenbuterol in 2018. The positive test – which the Canelo camp blamed on tainted Mexican meat – forced the postponement of their scheduled May 2018 rematch and resulted in Canelo’s six-month suspension by the Nevada Athletic Commission.

Since then, GGG has not been shy about questioning Canelo’s integrity, outright calling him a cheater and implying that his angry behavior could be the result of something akin to “roid rage.”

Whereas Duran flashed Leonard the middle finger, insulted his wife and generally behaved like a Barbarian in 1980, GGG is more diplomatic. But the words apparently have every bit the same sting. For almost four years, Canelo insisted he would not give GGG the spoils of a third fight. Even as DAZN signed both fighters in anticipation of a proposed third clash in 2019, Canelo scoffed at the mere mention of a third fight.

Eventually, enough years passed that a third fight didn’t seem to even matter anymore. Canelo was unifying the super middleweight division with impressive knockouts of Callum Smith, Billy Joe Saunders and Plant, while GGG was struggling with Sergiy Derevyenchenko and taking out soft touches like Steve Rolls.

The time for a third fight, it appeared, had passed.

But then, a breakthrough. Earlier this year, Canelo’s anger cooled enough that he decided to give GGG another opportunity. Before his May challenge of Dmitry Bivol for the light heavyweight title, he signed a two-fight deal that included the GGG rubber match. Unlike Duran, who upset Barkley in 1989 to earn the third Leonard fight, there was no real reason for a third Canelo-GGG fight. Whether it was because of economics, or because GGG aged – or both – Canelo decided it was time.

Of course, he didn’t anticipate losing to Bivol in one of the year’s biggest upsets. With GGG’s impressive stoppage of Ryota Murata in April, suddenly, the rubber match seems a little more competitive than it appeared before – just as Leonard-Duran 3 suddenly became appetizing once Duran beat the bigger, younger Barkley.

Is it a fight that will live up to the first two – which were very good? It’s a valid question, as GGG is now 40 years old – eight years Canelo’s senior. The only evidence we can look to are the first two fights. Which show us that, after 24 rounds of warfare, there is very little that separates the two warriors. If styles make fights, then this one will be every bit as close and competitive as the first two.

Then again, it could turn out like Leonard-Duran 3 – which was a dreadful bore. Whereas Leonard-Duran I opened the 1980s with fire, Leonard-Duran 3 closed the decade with a yawn. At age 38, Duran proved too old (or too unwilling) to force the action, opting instead to follow Leonard around the ring. And though he won, Leonard appeared reluctant to do anything but take the safe route – favoring boxing and moving to pressuring and attacking. All in all, for a fight that had been so anticipated for nine years, it was a dud. It also turned out to be the final victory of Leonard’s career.

We shall see if Canelo-GGG is worth the wait – or not.

Matthew Aguilar may be reached at maguilarnew@yahoo.com