Close to seventy world champions have come out of the small island of Puerto Rico, and eleven of those fighters would be inducted into the International Boxing Hall-of-Fame. This summer Miguel “Junito” Cotto (41-6, 33 KOs) became the eleventh fighter out of the island to have his name immortalized at the Hall-of-Fame in Canastota, New York.

Trinidad was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2014. Cotto will be inducted into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame (NVBHOF) this upcoming August 27th as part of the Class of 2020. Once again, he will follow in Trinidad’s footsteps, who entered the NVBHOF in 2015.

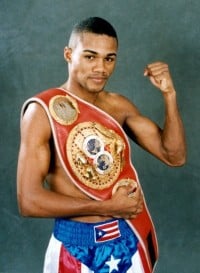

When Felix “Tito” Trinidad (42-3, 35 KOs) retired from boxing for the first of what would turn out to be three times, it was unclear who would pick up the mantle as the next star out of Puerto Rico.

Miguel Cotto would grab the torch Trinidad put down and leave a legacy of his own as one of the greatest fighters to come out of the island. Trinidad and Cotto inside the ring may not have reached the heights of past Puerto Rican greats such as Carlos Ortiz, Wilfredo Gomez, and Wilfred Benitez, but one could make an argument for each at certain points being as good as any of them.

With both fighters just one generation behind another, it’s curious to see how Cotto and Trinidad compare. They each fought in the same weight classes, with Trinidad starting his career as a junior welterweight and winning titles in the same divisions at welterweight, junior middleweight, and middleweight. Trinidad was the taller and overall bigger fighter, as he would fight as high as 170-pounds in his final bout against Roy Jones Jr. in 2008. Cotto was never a true middleweight, and most of his fights in the division were at a catchweight.

Both fighters accomplished so much. Jacob Rodriguez and I from NYF will cover a few categories and sub-categories measuring the career of both Puerto Ricans and, ultimately, what would happen in a head-to-head matchup.

Championships

Felix Trinidad

Record in Title bouts: (20-1, 16 KOs)

Championships Won:

IBF Welterweight – WKO2 Maurice Blocker

WBC Welterweight- WMD12 Oscar De La Hoya

WBA Junior Middleweight – WUD12 David Reid

IBF Junior Middleweight – WTKO12 Fernando Vargas

WBA Middleweight – WTKO5 William Joppy

Miguel Cotto

Record in Title bouts: (20-6, 16 KOs)

Championships Won:

WBO Junior Welterweight – WTKO6 Kelson Pinto

WBA Welterweight – WTKO5 Carlos Quintana

WBO Welterweight – WTKO5 Michael Jennings

WBA Junior Middleweight – WTKO9 Yuri Foreman

WBO Junior Middleweight –WUD 12 Yoshihiro Kamegai

WBC Middleweight –WRTD10 Sergio Martinez

For the most part, it is relatively even, with both pugilists having advantages in specific areas.

Trinidad won his first world title in 1993 against Maurice Blocker for the IBF welterweight championship. He would go on to become the longest reigning champion (6 years, 8 months, and 14 days) at 147-pounds and make 15 defenses of his title, with 12 coming by stoppage. The number of defenses at welterweight is second only to all-time great Henry Armstrong (19). Trinidad would unify the IBF and WBC 147-pound titles when he won a disputed decision over Oscar De La Hoya in September 1999. At the time, it was the highest-grossing non-heavyweight boxing PPV.

A long-awaited move up in weight took place next, with Trinidad winning the IBF and WBA titles at junior middleweight in 2000. That year was the greatest in the Cupey Alto, Puerto Rico native’s career winning the Ring Magazine and BWAA Fighter of the Year award. Following the run at 154-pounds, Trinidad would move up to middleweight to participate in a four-man tournament to crown an undisputed champion. He would win the WBA middleweight title with a five-round bludgeoning over William Joppy. The victory over Joppy would be Trinidad’s last victory in a championship match.

Trinidad’s final championship bout came when he lost to Bernard Hopkins in September 2001. Although Trinidad would fight four more times, this was the end of a legendary run from 1999 to 2001 that saw Trinidad at the sport’s highest level.

Cotto would win his first world title in September 2004 against amateur rival Kelson Pinto, stopping him in six rounds for the vacant WBO junior welterweight crown. After six title defenses, Cotto would move up to welterweight at the end of 2006, stopping fellow Puerto Rican Carlos Quintana for the vacant WBA welterweight title. Much like Trinidad’s 2000, Cotto had a star-making year in 2007, winning significant fights at Madison Square Garden against Zab Judah and Shane Mosley.

In July 2008, Cotto would lose a highly controversial fight to Antonio Margarito via eleventh round stoppage. At the time the fight occurred, the match with Margarito was seen as another chapter in the storied rivalry between Mexico and Puerto Rico. However, in the Mexican’s next match, it was found that he had tampered with hand wraps that would lead to a suspension from the sport, putting into question the Mexican’s victory over the-then undefeated Puerto Rican. Cotto would rebound by becoming a two-time welterweight champion stopping Michael Jennings in five for the vacant WBO title.

After losing to Manny Pacquiao at a catch weight of 145-pounds, Cotto moved up to junior middleweight and won the WBA junior middleweight championship against Yuri Foreman in June 2010 at Yankee Stadium. He would make two-title defenses, which included a victory over Margarito in a rematch before heading into a massive fight with Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Cotto would not prevail against Mayweather Jr., despite giving the undefeated defensive master his most competitive fight since Jose Luis Castillo. Following another defeat at the hands of Austin Trout, Cotto joined forces with Freddie Roach for the final chapter of his career. He would move up to middleweight to challenge Sergio Martinez and shockingly defeat the Argentinean for the lineal and WBC middleweight championships.

The victory over Martinez gave Cotto the distinction of being the first Puerto Rican four-division champion and one of only twenty-one men to accomplish this feat in boxing history. Following the final event fight of Cotto’s career against Saul “Canelo” Alvarez in November 2015 that resulted in a unanimous decision loss, the former Olympian moved back down to junior middleweight. This move garnered Cotto another world title at 154-pounds against Yoshihiro Kamegai before retiring in December 2017, losing his final bout to Sadam Ali.

Examining all of the championships won by Cotto and Trinidad, the more charismatic power-puncher has an edge due to none of his titles being vacant. It wasn’t until he moved up to 154 that Cotto won a championship from a then-current champion. But, Cotto made six defenses of his title at 140 and is a two-time champion at 147 and 154. Cotto’s victories over Foreman and Martinez are slightly compromised as the pair had knee injuries that affected their performances.

In the 1990s, Trinidad was the most consistent welterweight with the length of his title reign and number of defenses. Welterweight could be the deepest weight class in boxing history, and while Trinidad may not be at the top of the division historically, he was one of its defining champions for a decade. Although only at 154 for a short stint, Trinidad made an impression in the division that gives him credence as one of the best the weight class has seen behind fighters such as Thomas Hearns and Mike McCallum.

“He was a phenom at welter, but at welterweight, you always got the sense that he could be toppled somehow like he needed to fill out a little,” stated former HBO commentator Max Kellerman to Ring Magazine. “At middleweight, he was fighting bigger guys, like Bernard Hopkins, who could take his punch. But at junior middleweight, he looked like he was in his glory. He was basically the same guy at welterweight, only he looked sturdier. I would say we never really got to know him at junior middleweight because he was there briefly, but you could argue that was him at his very best.”

Cotto’s championships in four weight classes make this close and can’t be understated. Only five male champions from Puerto Rico have won titles in three weight classes, including Wilfred Benitez, Wilfredo Gomez, Hector Camacho, Wilfredo Vasquez, and Trinidad. At 26 fights, Cotto has also fought in more championship bouts than any other Puerto Rican fighter. However, Cotto’s legacy in any of the four divisions pales in comparison to Trinidad at welterweight and junior middleweight. The longevity at welterweight and unifying titles twice puts Trinidad ahead in this category.

Championships: Advantage – Trinidad

Competition

Trinidad: (12-3, 7 KOs) against world titleholders

Cotto: (16-6, 12 KOs) against world titleholders

There isn’t much separating Cotto and Trinidad in the competition department. No fighter can step into the ring with every single top opponent of their era, and these two weren’t known for avoiding challenges.

Trinidad won his first world title at 20 years old and was considered one of the top fighters at welterweight throughout the 1990s. 1994 was a breakout year for him when he faced veteran Hector Camacho, who was one of three fighters to make it the full 12-round distance during his title reign. That year he also scored two impressive stoppages against undefeated top contenders Yori Boy Campas and Oba Carr. He was dropped in the second round in both fights and bounced back to stop both opponents, stopping Campas in four and Carr in eight.

With the momentum of an outstanding year behind him, on the horizon loomed a title unification with WBC welterweight champion and pound-for-pound kingpin Pernell “Sweet Pea” Whitaker. The two fought on the same card in November 1995, but as it would turn out, Trinidad would find himself squaring off with his promoter more than opponents from 1995-1998. This portion of Trinidad’s career was stagnant with two failed attempts and losses in court to promoter Don King to get out of a contract that would allow him to pursue the fights he wanted.

When a fight with Whitaker didn’t come to fruition in 1996, Trinidad turned his attention to the junior middleweight division for a potential showdown in what would have been an explosive fight against Terry Norris. Instead, Norris would leave King and pursue a chance to fight Oscar De La Hoya, leaving Trinidad to fight in a WBC title eliminator without an opportunity to face an elite opponent.

In 1998, Trinidad would sign an eight-fight 30-million-dollar deal with promoter Main Events in an attempt to get fights with other champions in the division, such as the WBA titleholder Ike Quartey. Another loss in the courtroom to King ended the pursuit of a clash with the Ghanaian jabber.

It wasn’t until 1999 that Trinidad finally became the main priority for King and got his opportunity to fight Whitaker. Unfortunately, Whitaker was no longer at his best, coming off a 17-month layoff after testing positive for cocaine. Trinidad would be the first fighter to clearly defeat the Virginian defensive wizard, winning a unanimous decision, fracturing Whitaker’s jaw, and scoring a knockdown in the second round. A win over an all-time great is notable, but the timing wasn’t right. A win over Whitaker in 1999 was less impactful than it would have been in 1995 or 1996. While many of this generation have complained about the lack of action or its inability to live up to the hype of the 2015s mega-event fight between Manny Pacquaio and Floyd Mayweather Jr., the same can be said tenfold for Felix Trinidad-Oscar De La Hoya.

Both men were 26 years old, undefeated, and known for their knockout power. The fight had the Mexico-Puerto Rico rivalry, rival promoters in Don King and Bob Arum, and was promoted as the most crucial welterweight battle since Ray Leonard-Thomas Hearns. Trinidad-De La Hoya had the potential to be one of the greatest fights of all time.

Unfortunately, the fight wasn’t the most entertaining and is known for being one of the more disappointing fights in boxing history. Potentially a clear and undisputed victory over an undefeated Oscar De La Hoya could have been the most significant in the boxing history of Puerto Rico; however, Trinidad had to settle for a disputed majority decision.

Although Trinidad has superior credentials at welterweight, Cotto, throughout his career, never faced the same promotional issues as his predecessor and entered the welterweight division at a time when it was filled with elite fighters. At welterweight, Cotto was able to face stiff competition and did so consistently. The 2000 Olympian would make five defenses over two reigns at welterweight, facing the likes of Carlos Quintana, Zab Judah, Shane Mosley, Antonio Margarito, Joshua Clottey, and quite possibly the best version of Manny Pacquiao during his three-year stretch at 147.

“The Mosley that Cotto beat was as good as anyone Felix Trinidad fought,” stated boxing historian Cliff Rold to Ring Magazine before Cotto’s fight with Yuri Foreman in 2010. “That motivated version of Shane was way better than David Reid, Yori Boy Campas, or Oba Carr. That Mosley was better than the faded version of Pernell Whitaker that Trinidad fought. That Shane was just as good as the De La Hoya, Trinidad barely beat in controversial fashion. “And Cotto was never shut out the way Trinidad was against Bernard Hopkins and Winky Wright. Cotto was competitive in his losses.”

While Cotto was competitive in each of his losses, it’s doubtful he would have won or done any better than Trinidad against the likes of Bernard Hopkins or Ronald “Winky” Wright. It’s hard to see Trinidad losing to the likes of Sadam Ali or Austin Trout. And while anything can happen in an unpredictable sport like boxing, a fight between Trinidad and Antonio Margarito would have been a complete brutal demolition at the hands of the Puerto Rican.

How Trinidad would have fared against the likes of Floyd Mayweather Jr, Manny Pacquiao, or Canelo Alvarez is another story. All three would have been favored over Trinidad, with Mayweather being able to execute the style that gave the Puerto Rican power puncher the most trouble. Trinidad would have the best chance at winning against Pacquiao and Alvarez, as both fighters never exhibited the level of lateral movement that fighters like Hopkins did.

Trinidad’s run at 154 was brief, and for some, he looked at his best at junior middleweight. One could say that both David Reid and Fernando Vargas didn’t have enough experience before facing the Puerto Rican three-division champion. Reid, a 1996 Olympic gold medalist, was handling his own against Trinidad, scoring a knockdown in the third round. That all changed in the seventh round when a quick left hook on the inside that was hard to see even on replay changed the fight leading to Trinidad dominating, scoring four knockdowns en route to a unanimous decision.

Vargas, for his part, at 22, had made five defenses of his IBF 154-pound title before facing Trinidad and earned victories over Ike Quartey, Yori Boy Campas, Raul Marquez, and Winky Wright. Quartey was a fighter that most fans would have loved to have seen Trinidad fight, and Wright ended up defeating Trinidad when they faced off in 2005. Youth and experience sometimes aren’t synonymous. In Vargas’ case, he had every right to face Trinidad due to his recent opposition before meeting the Puerto Rican.

Those who believe Vargas was too young may have also advised Wilfred Benitez never to face Antonio Cervantes to become the youngest champion in history. Or for Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns to fight when they did in 1981 as Hearns was only 22. Trinidad-Vargas has often been considered one of the greatest fights at 154. Ring Magazine rated the match as the best in the division’s history in 2002.

For fighters whose careers began over a decade apart, the two Puerto Ricans surprisingly have a common opponent in Nicaragua’s Ricardo Mayorga. The other boxer that they should have had in common is Shane Mosley. Much like a battle between Erik Morales and Juan Manuel Marquez, Trinidad-Mosley is one of the missed fights that could have taken place in the 2000s. The timing was never right for a clash as they were always in separate weight classes. The California fighter entered the welterweight division as the Puerto Rican was moving up.

The closest the bout came to taking place was after Mosley’s second fight with Wright, where Trinidad was set to face the winner. Mosley lost, and Trinidad would take an ill-advised match against Wright, leading to him announcing his second retirement. The pressure of fighting not just for yourself, your team, and your family but with the hopes and dreams of a country on your back can be daunting. The force of will Trinidad imposed on his opponents can only be compared to the pressure he internalized fighting for Puerto Rico each time he stepped in the ring. For this reason, the losses he suffered seemed to affect him significantly.

“He’s thinking I can’t let this guy not get knocked out,” stated Bernard Hopkins about his fight with Trinidad. “I can’t let this guy win this fight because my country will never forget this. He’s riding on pride, he’s riding on how much it will make him bigger than he already is, he’s riding on I did something that he didn’t like either. I don’t care how good you are; that’s a lot man.”

Cotto, on the other hand, took his losses in stride. After losing to Margarito in 2008, he returned to fight three times in 2009, including taking on a fighter known for being avoided at the time, Joshua Clottey. Cotto may never have been considered one of the best fighters pound-for-pound like Trinidad was in 2000, but a component of greatness is how you respond to your losses. And Cotto did not allow his defeats to define him.

While it is close, ultimately, Trinidad’s lost years between 1995 through 1998 hurt him when compared to Cotto. Missed fights with a prime Pernell Whitaker, Ike Quartey, Terry Norris, and a pound-for-pound matchup with Shane Mosley weren’t the fault of Trinidad but unfortunately never took place. Cotto’s tenure in a rugged welterweight division and fights with three of the best fighters of the last decade put him over the top here.

Competition: Advantage – Cotto

Career/Impact/Popularity

Over the last 30-plus years, Cotto and Trinidad were far and away the most popular Puerto Rican fighters. Along with De La Hoya and Canelo, they were also arguably the most favored Latin fighters. Cotto’s career lasted longer than Trinidad’s initial run from 1990 to 2002. Many forget that Trinidad fought just once before first retiring at the age of 29 following the loss to Hopkins. Cotto spent 16 years as a professional from 2001 to 2017 and is unlikely to make any return.

From a popularity standpoint, Trinidad was the more beloved fighter. His charismatic personality captivated those on the island, bringing about a rare die-hard fanaticism in boxing. Trinidad’s refusal to learn English endeared him more to the people as they viewed him as not just a sports idol but as an everyman and truly one of them.

“My feeling on Trinidad was I always thought he was going to be a star even though he didn’t speak English,” stated former HBO Sports senior vice president Kery Davis to Ring Magazine. “The theory was anybody who is that exciting to their own culture has something that would sell to everyone. That’s the same way I felt about Pacquiao.”

Trinidad’s acclaim peaked in 2001 when he faced off against William Joppy at Madison Square Garden in front of a crowd that could only be described as pandemonium. Over 20 years later, the scene at Trinidad-Joppy hasn’t been duplicated, with fans’ level of adoration on display for a fighter. The connection between Trinidad and the Puerto Rican contingency is scarce. During his ring entrances, the adulation laid upon the three-division champion was always reciprocated by his effort and magnetic demeanor.

“The people have been with him watching his career, and people know that he never quits and that he accepts all challenges during his career,” said father and trainer Felix Trinidad Sr. to Ring Magazine. “Out of boxing, he’s been a good human being; the people give love to him, and he gives back that love when he signs autographs, when he takes pictures and when he takes time with the fans. I think he deserves that popularity right now. It came with time and with his behavior in and out of the ring, and even though he is not a champion, people still call him champion when they see him.”

Throughout their careers, Cotto and Trinidad made Madison Square Garden a pseudo-second home. Trinidad fought in the famed arena six times and Cotto 10, with each man fighting the final fights of their career in the building. While Trinidad did have some notable moments in the Garden, Cotto made his fights at MSG a national holiday. Cotto fought on the Puerto Rican Day parade weekend on five separate occasions scoring victories each time. The match with Zab Judah in June 2007 was particularly memorable, coming close to reaching the same level of madness and fan uproar of Trinidad-Joppy.

“New York is a second Puerto Rico,” noted Carlos Narvaez Rosario, former sports editor for El Vocero, a newspaper in Puerto Rico. “There are more than a million Puerto Ricans living there today, and there are three times more Puerto Ricans in the United States and the world than on the island. And the history of Puerto Rican boxing originated there in New York.”

On the pay-per-view market, both Hall-of-Famers were successful. Trinidad’s bout with De La Hoya may have been the most significant fight either man was a part of, but Cotto’s fight with Pacquiao sold more than 110,000 PPVs in Puerto Rico, a record at the time.

In Trinidad’s era, the only major attraction outside of the heavyweight division that was a legitimate PPV star was De La Hoya. Since Cotto didn’t have multiple retirements with significant gaps of time between fights, he had the advantage of stepping in the ring with three names that were just as big or bigger than De La Hoya in Mayweather, Pacquiao, and Canelo. Two of the three fights with the aforementioned three garnered over one million PPV buys.

Cotto has also been a part of the boxing world outside of the ring, with Miguel Cotto Promotions promoting fighters and putting on events on his native island. For the most part, a Trinidad appearance is scarcer but hasn’t deflated his popularity, as he is still an adored sports figure. “He’s truly their hero, someone they can associate with,” stated former Everlast executive Joe Guzman. “He’s like their Joe DiMaggio. He’s just a warm human being, and it comes across – he’s real.”

While Trinidad may have been the more overall popular fighter, Cotto’s career is one to model after. Some of Trinidad’s prime years in the 1990s were wasted due to promotional drama and courtroom cases with huge fights fading away. Cotto seemed to squeeze every bit of his career, maximizing his fan base as it grew throughout the years. The four-division champion had a more aloof and stoic personality which in comparison to Trinidad may have turned off some fans. But, Cotto never portrayed himself as anything other than who he was.

It may come down to preference and age in choosing between the two. In the same way, some people prefer Tobey Maguire or Michael Keaton as their respective Spider-Man and Batman to contemporary versions of the characters portrayed by Tom Holland and Robert Pattinson. When it comes down to it, Puerto Rico was fortunate to have two influential and great fighters emerge not too far apart. The number of memories in the ring they both gave fans make their impact on boxing in Puerto Rico immeasurable.

Career: Draw

Head-to-Head

The Puerto Rican Hall-of-Fame duo gave fans numerous unforgettable fights. A match between Cotto and Trinidad would have undoubtedly been exciting and the biggest clash between two Puerto Rican fighters in the history of the sport.

Of the two, Cotto had more dimensions, with portions of his career mimicking Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. breaking down opponents with punishing barrages to the body. Cotto also had the ability to move laterally and fight on his back foot behind a jab. Due to the severely one-sided nature of Trinidad’s defeats at the hands of Hopkins and Wright, the power-puncher has been underrated by pundits as the years have passed. The losses to Hopkins and Wright highlighted that Trinidad’s only secondary game plan was to apply more pressure and fight harder. There was no plan B for Trinidad.

Looking at his record closer and in his prime, you will see a fighter who was technically proficient with power in both hands and, at times, a counter-puncher. Trinidad wasn’t the type of power puncher to bum rush an opponent ala a Marcos Maidana, but instead, survey the situation before forming his attack. He was deadly accurate with a plethora of fights averaging a connect percentage over 50%.

In a fight against Cotto, Trinidad’s most significant advantage would be his conditioning and more extended reach. Known for consistently using running as part of his training regimen, Trinidad was similar to an avalanche getting stronger the longer the fight went. “I would train hard, but not always,” said all-time Puerto Rican great Wilfredo Gomez when asked about Trinidad. “And sometimes that can be the difference between winning and losing. His father was key in his success, too, because Tito had the utmost respect for him, and he would do whatever Don Felix would ask of him.”

Although Cotto’s fight with Margarito is marred with controversy, it does give an example of how Trinidad could have walked away with a victory in a clash with his fellow Hall-of-Famer. And to a lesser extent, his fight with Lovemore N’dou. Cotto didn’t know how or chose not to clinch his opponents. And against Trinidad, when the fight reached its final stages where fortitude is most needed, the taller power-puncher would be at his most dangerous.

Cotto did have underrated hand speed, intelligence, and stellar timing with his jab. The jab against Trinidad would have been Cotto’s most formidable weapon that could have done the most damage. Hopkins and, to a greater extent Wright used the jab to keep Trinidad resetting. However, Hopkins and Wright were more prominent fighters that were master technicians, and it’s doubtful that Cotto could have mimicked what they were able to accomplish against Trinidad.

It’s all theory, but a fight between Trinidad and Cotto may have played out similarly to Trinidad’s victories over Oba Carr and Fernando Vargas. A second-round knockdown from Cotto was followed by a few back-and-forth rounds, with each man landing hard shots. Over time, the pressure of Trinidad would be enough to wear down Cotto to a late stoppage.

Head-to-Head: Advantage-Cotto

When equating side-by-side two Hall-of-Famers, you are bound to get differing viewpoints. NYFights Jacob Rodriguez has a divergent take on a battle between Cotto and Trinidad.

A matchup between Puerto Rican boxing stars Miguel Cotto, and Felix “Tito” Trinidad is at the top of the list of fantasy matchups for most boxing fans. As my colleague Hector mentioned, each of these fighters had distinct career paths and were great in their own right. In addition to being loved by their Puerto Rican fan base, both fighters are revered globally. However, when discussing who would win a fight between these two iconic fighters, that’s where the consensus ends.

In my experience, when discussing a fantasy match between Cotto and Trinidad, these fighters seem to polarize boxing fans, with most believing that Cotto will succumb to Trinidad’s Superman-like power in both hands. And while I agree that Tito’s power coupled with his laser-like punching accuracy was an insurmountable obstacle for 43 of his opponents, three opponents were able to defeat the Puerto Rican “demigod.”

What was Trinidad’s Kryptonite? “Ring Generals.” Felix had a hard time with “pure” boxers, but the lanky Puerto Rican native always found a way to defeat those pesky opponents. However, “Ring Generals” were different. Like great military generals, Hopkins, Wright, and Jones knew how to strategize, use the terrain, and their assets to neutralize Tito’s power. I classify Miguel Cotto as a ring general for his ring-generalship and ability to adapt to what his opponents were doing during a fight.

Head-to-Head: Advantage-Trinidad

I believe that Miguel Cotto is the better all-around fighter. He has a great jab, can box very well, and positions himself to put combinations together better than most fighters of his era. All I have to do is remind you of how Oscar De La Hoya completed outboxed, if not shutout Tito Trinidad for the first seven rounds of their fight in 1999. Miguel Cotto has a quick and snappy jab. In the first few stanzas of this match, Miguel Cotto will establish his jab and stunt Trinidad’s forward momentum.

Once Cotto has set a comfortable pace, he will move, land combinations, and then slide away much like De La Hoya did against Tito. Cotto doesn’t get enough credit for being a solid body puncher. Miguel’s double hook combination to the body and then the head punished opponents throughout his career. Next, Cotto will attack Tito’s body and follow up with uppercuts. A confused and frustrated Tito will increase his forward momentum to land his power punches. Miguel Cotto doesn’t have one-punch knockout power. However, he hits hard enough to physically and mentally break down opponents throughout the fight.

While I believe that Cotto will outbox Tito Trinidad, none of it will matter if he gets knocked out, which can likely happen. However, Miguel Cotto is a resilient fighter that can take a lot of punishment before he gets knocked out. He withstood much punishment from Manny Pacquiao and Antonio Margarito, who possibly used hardened hand wraps during their match. It is foolish for one to think that Tito’s punching power will not affect Cotto in this fantasy match; it certainly will. However, when Tito gets unconfused and starts to land his shots, Cotto will be ahead on score cards and weather Tito’s power to hear the final bell.

Result: Miguel Cotto defeats Felix Trinidad via unanimous decision.

At its purest, boxing is a sport of moments. Both Cotto and Trinidad had the ability to capture the hearts of an audience to gain a connection that could impact them emotionally, whether they won or lost. The failures of prospective future leaders of Puerto Rican boxing, such as Juan Manuel Lopez and Felix Verdejo, highlight how difficult it can be to live up to the expectations of the island nation.

Cotto and Trinidad are integral to the history of Puerto Rican boxing. Future fighters from the island, such as Edgar Berlanga, Xander Zayas, and Omar Rosario, amongst others that view them as their idols, will have big shoes to fill when it’s their time.