USA Boxing recently revealed guidelines for transgender athletes for their 2024 Boxing Rule Book.

Even as a layman, I found the content of these guidelines eyebrow raising.

I began to suspect that when coming up with these policies, USA Boxing failed to do meaningful due diligence in consulting any actual trans athletes or experts. So I consulted one.

Danne Diamond (they/them) is director of policy and programs for Athlete Ally, an organization that works to “dismantle the systems of oppression in sport that isolate, exclude and endanger LGBTQI+ people.”

Diamond is also a 3-time Muay Thai national champion, and continues to coach the sport.

Diamond graciously lent their time to go over these guidelines with me.

Q n A On Transgender Participation In Boxing With Danne Diamond

BJ: What is your initial reaction to reading these guidelines? Do you feel they’re positive and/or inclusive? Or worthy of criticism and/or inconducive to progress?

Danne Diamond: Overall, we were encouraged to see that USA Boxing did not outright ban transgender athletes – especially transgender women.

We have seen outright bans as an ongoing trend, not because there is any definitive new science, but rather a deep fear and misunderstanding about who transgender people are.

Transgender people – and transgender athletes – are like everyone else: sometimes we win, sometimes we lose, but we just want an opportunity to participate and be a part of a sports community just like everyone else.

With that said, we were deeply concerned to see an outdated surgical requirement for participation and no pathway for trans, nonbinary and intersex youth to participate in line with their gender identity.

BJ: What stands out about the rules from the perspective of one who coaches and fights martial arts, and what stands out about them from your perspective as Policy And Program Director of Athlete Ally? Are they the same things or different?

Danne Diamond: I care deeply about women’s sports, and especially women’s combat sports.

I competed in the women’s category for a decade, and am a 3x national champion in three different weight classes. I know how hard women work, and the uphill battle it is to get even the smallest amount of respect.

What has been heartbreaking for me as a former fighter and current coach, and someone who works at the intersection of sports and social justice every day, is just how unwelcoming and scary sports has become for trans, nonbinary and intersex people – but especially transgender women.

I believe that everyone can be included in boxing, no matter who they are or where they’re from, and it still can be safe and fair. We do not have to latch on to this false choice.

The following are USA Boxing’s guidelines for what a boxer who transitions from male to female must conform to in order to be eligible to compete in the female category:

* The athlete has declared that her gender identity is female and has completed gender reassignment surgery.

BJ: This is the guideline easiest for the layman to understand. Does undergoing gender reassignment surgery make a difference to any variables on a medical or a scientific basis?

Or could this be seen as more of a performative guideline?

I ask because I have female trans friends who have elected to disclose to me that while they are on hormone therapy, they have chosen not to remove genitals they were born with.

I’m concerned if gender reassignment surgery doesn’t affect things on a medical or scientific level, then a mandatory gender-reassignment-surgery guideline could be used as a way to discredit a certain group of trans women.

DD: There is no evidence that undergoing gender-affirming surgery is going to impact an athlete’s performance.

Undergoing gender-affirming surgery is a big decision, and inaccessible to most people.

Many gender-affirming surgeries for adults are now covered under insurance, but if an athlete doesn’t have insurance or access to money to cover other out-of-pocket surgery-related expenses, many people simply don’t have the time or money to get the care they need.

We are now also living through a moment where gender-affirming care for adults is under attack, so to be able to access this kind of care is getting harder and harder.

To put it more bluntly, and forgive me for being crass: genitals don’t play sports, people do.

Someone’s genitals are not a determining factor of competitive excellence, and we shouldn’t be reducing anyone to what is or isn’t in their pants.

USA Boxing Guideline:

* The athlete for a minimum of four years after surgery has had quarterly hormone testing and presents USA Boxing documentation of hormone levels.

BJ: By hormone levels, are they referring to testosterone levels or estrogen levels or both?

Also, is four years an arbitrary number or does something happen to the body that it takes four years to adjust to?

If I’m interpreting the rule correctly, it means anyone who transitions from male to female cannot compete for four years, which, to an athlete, may seem like an eternity of inactivity. So that’s another reason why I’m trying to determine if four years is the magic number or an arbitrary number.

Danne Diamond: You are asking all the right questions!

Many of these policies are written by people with no input from medical professionals who actually care for transgender people or have even met a transgender person.

So there is no clarity about what is meant, but it can be inferred that the policy is talking about testosterone levels.

Four years is a long time, and this number most likely came from the 2015 IOC Consensus Statement.

To give you a bit of history on eligibility criteria for transgender athletes at the IOC level:

In 2004, the IOC released its first consensus statement on transgender athletes. All of the IOC guidance is nonbinding, but many international federations (IFs) and national governing bodies (like USA Boxing) integrated this consensus statement into their policies.

USA Boxing hadn’t updated its policy for years, you can see the previous policy on Chris Mosier’s website, and still followed the 2004 Stockholm Consensus statement which required surgery for trans athletes.

In 2015, the IOC released a new consensus statement.

This removed the requirement for surgery for all trans athletes, and for trans women, outlined that an athlete must have 1) declared their gender identity is female (and must remain so for four years); 2) demonstrated that her T level has been less than 10nm/l for the duration of 12 months and remains that way.

Trans men were permitted to compete without restriction (as long as they were in line with WADA).

USA Boxing Guidelines:

* The athlete must demonstrate that her total testosterone level in serum has been below 5 nmol/L for at least 48 months prior to her first competition (with the requirement for any longer period to be based on a confidential case-by-case evaluation, considering whether or not 48 months is a sufficient length of time to minimize any advantage in women’s competition.

* The athlete’s total testosterone level in serum must remain below 5/nmol/L throughout the period of desired eligibility to compete in the female category.

BJ: In layman’s terms, what exactly is an nmol/L, and why is it important that it’s remained below 5 for 48 months? If the nmol/L is higher than 5 within the given timeframe, does that give the trans athlete an advantage they otherwise would not have?

Danne Diamond: So, nmol/L= nanamoule per litre. Again, you’re asking the right questions.

In general, the testosterone ranges we see in sport policy for trans women range from 2.5nm/l to 5nm/l to 10 nm/l.

These are based on what is considered “typical” ranges for both cisgender men and cisgender women (who are not elite athletes), but does not take into account the many ways in which cis men and cis women may have T ranges under or over these typical ranges, and how T is levels are impacted based on testing method, time of day, et cetera.

For more on this, I’d highly suggest you read through the Exec Summary of the Candian Centre for Ethics in Sport Report.

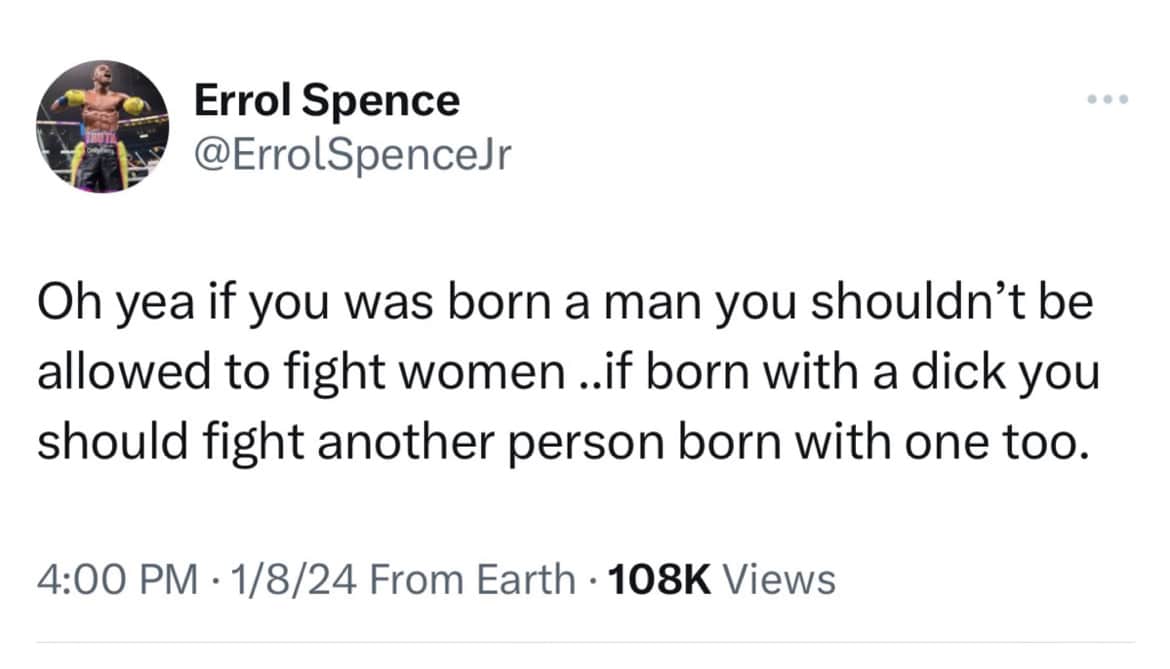

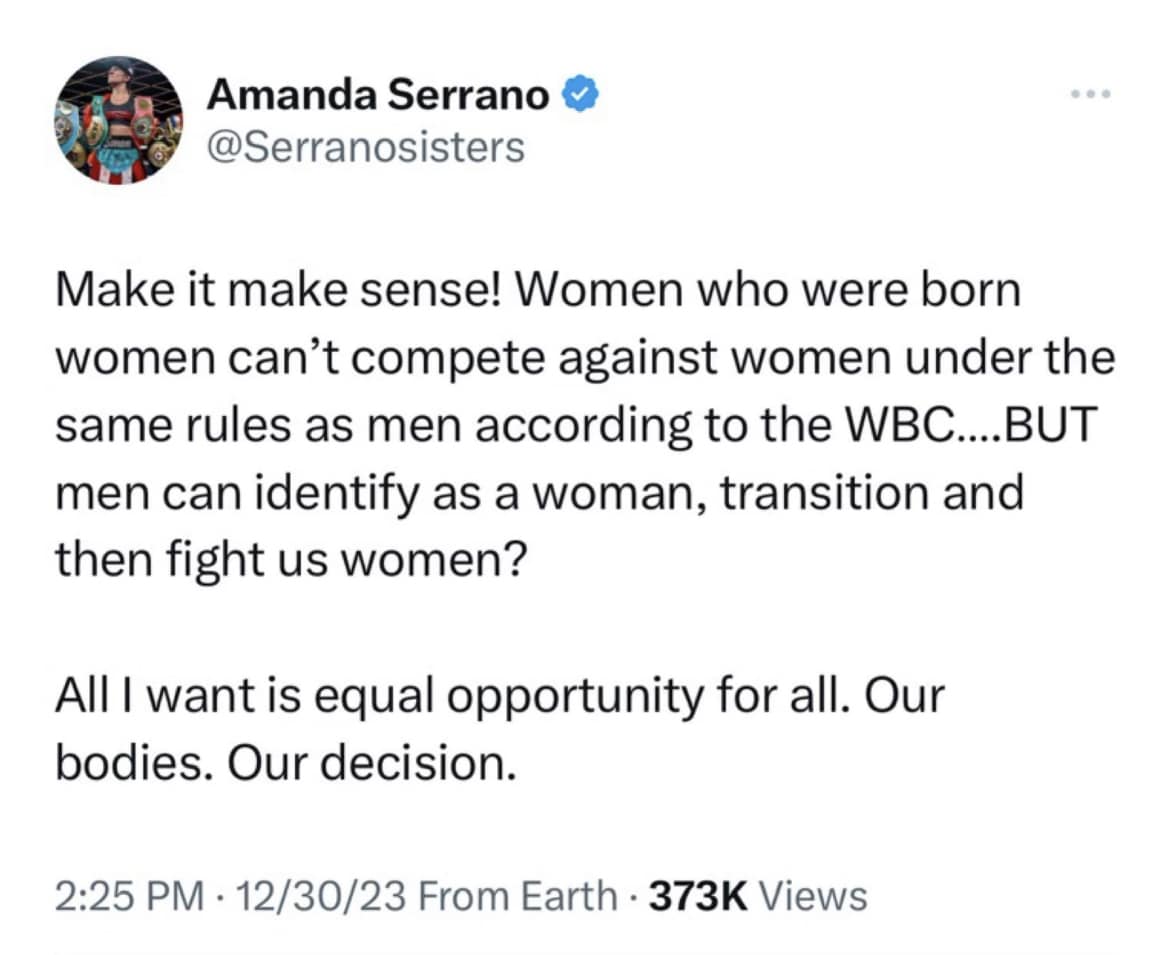

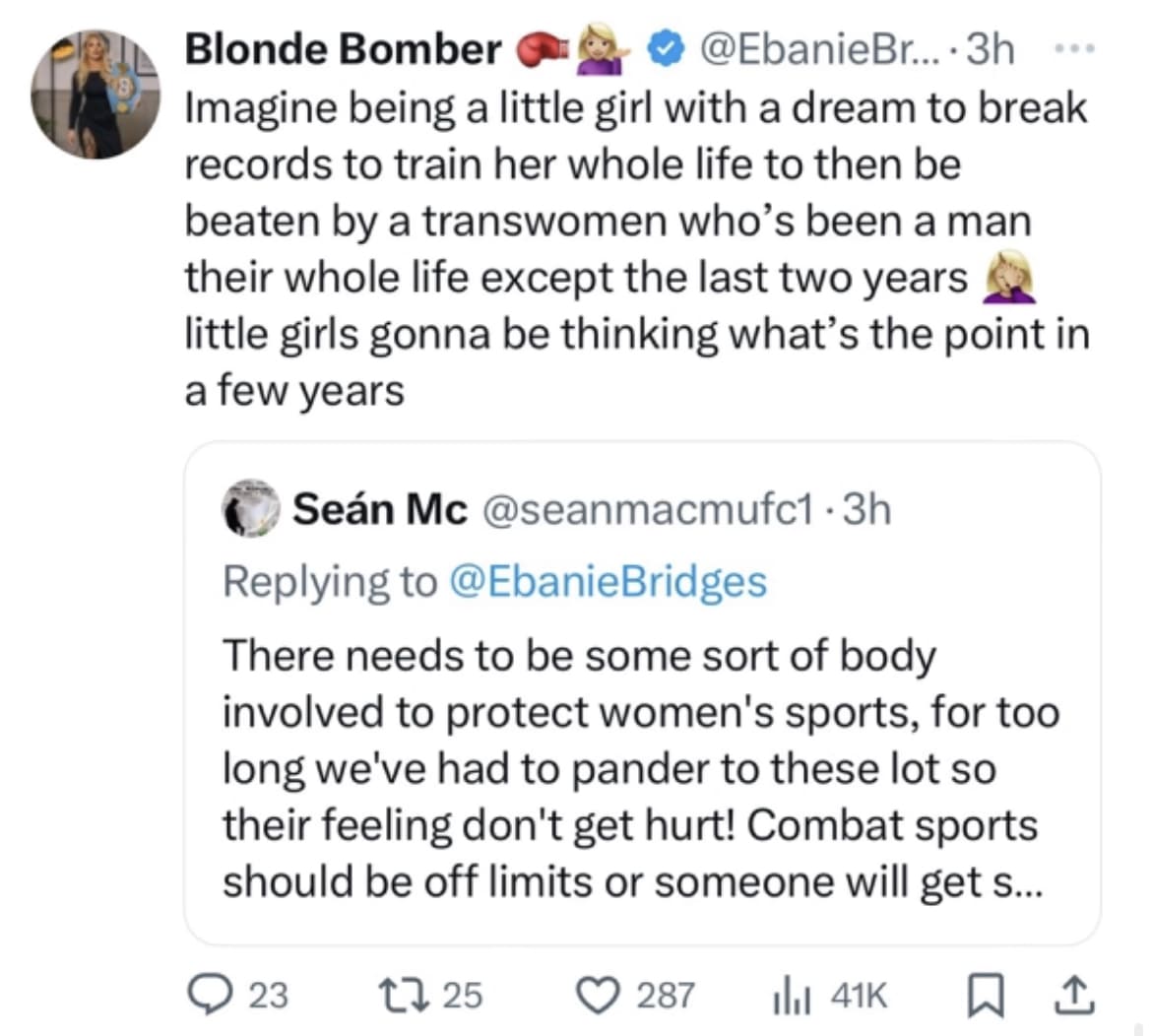

BJ: #Boxing Twitter has been unfortunately pretty awful about these rules. There’s been a heavy amount of transphobic nonsense, and it’s been very disappointing to see it coming from some elite fighters.

BUT there are elite female boxers, such as Amanda Serrano or Seniesa Estrada whose concern comes from (seemingly) not a transphobic place, but from the fact they have male sparring partners, they feel their male sparring partner’s power, and, to the best of their knowledge, fighting a trans female boxer is as dangerous as fighting a male boxer.

What would you say to them? Is this a valid concern? Or is there data that could assuage them?

DD: We all care about athlete health and safety and making sure fairness is maintained in Boxing. I think it’s important that we address people’s honest questions head on.

Unfortunately, there are so many misconceptions about transgender people because so many people have not met a transgender person (or do not believe they have).

The media has put in our collective consciousness that trans people are scary, that trans women are bigger, faster, stronger – but that’s simply not the case.

Transgender women are so diverse, just like cisgender women. Just because someone is transgender doesn’t mean that they inherently have an advantage in sport, which was outlined by the new IOC guidelines in 2021.

BJ: Did USA Boxing do a good job preparing these guidelines? Or would it have behooved them to consult more trans voices in their preparation?

DD: These guidelines were developed in 2022.

There are some confusing and false claims in the policy, including that the policy follows the 2015 Consensus Statement.

The 2015 statement notably does not require “gender reassignment surgery” for either transgender women or men, and allows transgender women to be eligible as long as their testosterone levels are below 10nmol/L for at least a year prior to her first competition. I would be shocked if there were any transgender, nonbinary or intersex voices consulted at all in the development of this policy.

BJ: Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you feel is important for readers to understand?

DD: If you’re reading this article, my guess is that you love boxing as a fan, as a fighter, or as a casual participant.

Think about how much boxing has brought to your life – the power, the confidence, the community. And then think about all of that being taken away from you just because you’re different, and because the world doesn’t understand who you are.

Imagine seeing your humanity put up for debate around the country and now your sport wants to exclude you, too.

At the end of the day, trans, nonbinary and intersex people are just that – we are people. We want to be treated with respect and dignity like everyone else. And we want to fall in love with boxing just like you.