Salvador Sanchez had a dervish of a fighter in front of him, an unknown-but-powerful substitute from Ghana named Azumah Nelson that got in his face, attacked from all angles, and cared not one bit about the odds against him or the Mexican maestro’s almost pristine reputation.

But through what was the most unexpectedly difficult challenge of his 2 ½ year reign as WBC featherweight champion, Sanchez’s stoic expression never changed. Through 14 torrid rounds, he calmly countered Nelson’s rushes – steadily increasing activity like a conductor building to a crescendo.

By the final round, Nelson was battered and spent. Sanchez moved in for the kill, dropping and stopping his game challenger with a volley of pinpoint punches. Afterward, the physical dynamo took a victory lap around the ring – without hardly a heavy breath or a mark on him. Just 23 years old, an already legendary career appeared limitless in its possibilities, as a jump to face lightweight champ Alexis Arguello was potentially on the horizon.

Twenty-two days later, Salvador Sanchez – arguably the greatest Mexican fighter in boxing history – was dead. Forty years ago on August 12, 1982.

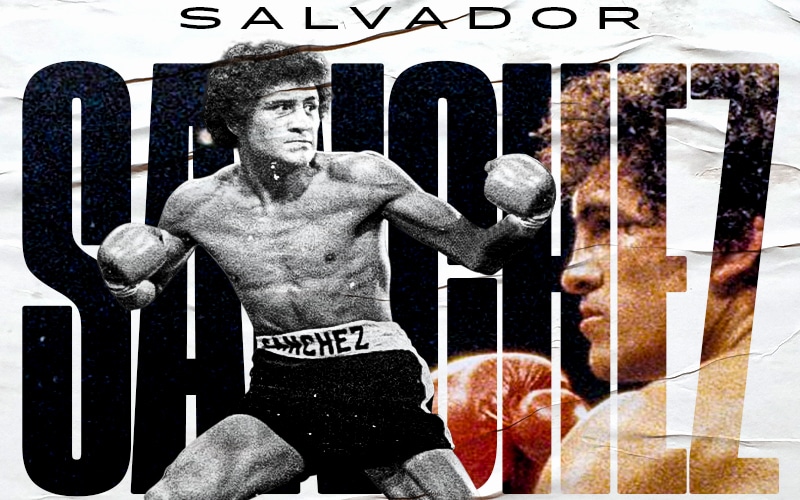

It didn’t seem possible, the terrible news that came out of Queretaro, Mexico, that day. The Nelson fight was so fresh in everybody’s mind – how could this brilliant fighting machine with the fresh face and the puffy hair be gone? Since bursting onto the scene on February 2, 1980 – the afternoon he upset Danny “Little Red” Lopez via 13th-round TKO – Sanchez had become a staple on American television and one of the most popular fighters of the era.

And he was popular despite his approach – which was more cerebral than the styles of many of his Mexican compatriots. Sanchez didn’t stand and trade, eating needless shots just to land his own. Instead, he used lateral movement, angles, parries, feints, and brains to outthink his opponents before unleashing a controlled display of speed, timing, and precision. His conditioning paved the way as he trained endlessly in the Mexican mountains. His doctor said he could spar for five minutes, and his heartbeat would return to normal in 45 seconds of rest.

He also earned respect by fighting – often. Consider, in his title-winning year of 1980 alone, he beat Lopez twice, Ruben Castillo, Patrick Ford, and Juan LaPorte. All were either former or future world champions or top five contenders. The two Lopez wins were masterpieces, as the slow, plodding slugger had no answer for Sal’s incomparable counterpunching abilities.

Incredibly, in an obviously great year for the sport, Sanchez was beat out for “Fighter of the Year” honors by Thomas Hearns.

As great as 1980 had been, however, 1981 turned out to be the legend-maker. On August 21 of that year – in the barn-like confines of the Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion, Sanchez met Wilfredo Gomez in arguably the most anticipated Mexican-Puerto Rican matchup of all time. Gomez, 32-0-1 with all 32 by knockout, was considered by many to be both the hardest puncher and best pound-for-pound fighter in boxing. He reigned at 122 pounds with an iron fist and moved up to 126, hopefully, to finally receive a challenge.

Many were convinced Gomez would knock Sanchez out.

With Sanchez’s mariachis battling Gomez’s salsa band, the fighters entered the ring to a wild throng. But minutes into the fight, the roles reversed. Sanchez, the boxer, became the puncher, shocking Gomez by dumping him onto the seat of his trunks with a sneaky combination. Sitting on the deck in disbelief, Gomez stared up at Sanchez with awe. And though Gomez got up and fought hard the rest of the way, Sanchez’s emphatic first round established his dominance. As the fight wore on, Sanchez’s poetic fists caused a grotesque swelling around Gomez’s eye, and Sanchez punched him through the ropes to end it in the eighth.

It remains one of the greatest big-fight performances in boxing history and reiterates what made Sanchez so great: he performed his best when the stakes were highest.

The Nelson fight on July 21, 1982, was Sanchez’s ninth defense. At the time of his death, “Chava” was already in training for his next fight – a September 15 rematch with LaPorte scheduled for Madison Square Garden. But Sanchez had broken training camp for what are unknown reasons – mysterious for a fighter known for his dedication. On the way back from wherever, in the middle of the night on a dark stretch of Mexican highway, Sanchez reportedly was trying to negotiate a high-speed pass in his beloved Porsche (he loved sportscars). He crashed head-on into a truck and died instantly.

The boxing world mourned, as did his opponents, many of which – including Nelson, LaPorte, and Gomez – attended the funeral in his native Tianguistenco Santiago, Mexico. Renowned sportscaster Howard Cosell – who called many of Sanchez’s fights – paid his respects with a lengthy tribute. The headline on “KO Magazine” said it best: “The Fists of Elegance are Silenced.”

We never got to find out just how much greater Sanchez, 44-1-1 (32 knockouts), could’ve been. At 5-foot-6, it’s possible that 135 pounds could’ve been a bridge too far. Arguello would have had four inches in height and reach on him and a strength advantage. But, had Sanchez moved up to 130 pounds and stuck around for a couple of years, he’d have possibly met the challenge of a young lion named Julio Cesar Chavez from Culiacan. And that is the stuff of fantasy.

It never happened. But what we got was greatness nonetheless.

Matthew Aguilar may be reached at maguilarnew@yahoo.com